The flying ability of ancient lizards is one of the biggest questions in the field of paleontology to date.

If asked whether there are any flying dinosaurs, many people might picture an animal with long, leathery wings, sharp claws, and a gigantic beak. However, the creatures you envision are not dinosaurs; they belong to a group of flying reptiles known as pterosaurs (often mistakenly referred to as flying dinosaurs, a term that has gradually gained acceptance in the community).

These animals are remarkable in their own right: they were the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight, 60 million years before birds and 170 million years before bats.

They were the first vertebrates to evolve powered flight.

People often consider them dinosaurs because some children’s books refer to pterosaurs as flying dinosaurs. In short, for various reasons, pterosaurs are indeed a group of paleontology that deserves attention in their own right.

The flying ability of pterosaurs remains a mystery even today. How their powered flight evolved has yet to be clearly answered.

The evolution of flight in birds has been described many times through scientific studies. The evolutionary path of bird flight began with the development of feathers covering their bodies, followed by gliding through trees, and eventually powered flight.

However, even the earliest known pterosaurs had specialized flying abilities, and their bodies were shaped to adapt to soaring in the sky. To date, we have not found any fossils that provide clues about how pterosaurs adapted from ground-dwelling to soaring in the air.

During the Mesozoic Era (252 million to 66 million years ago), pterosaurs and dinosaurs coexisted. They came in many forms and were found all over the world. Although the oldest pterosaurs were very small, no larger than a seagull, some later members evolved into the largest flying animals to ever exist on the planet, with wingspans comparable to small airplanes.

Despite being close relatives of dinosaurs, pterosaurs and dinosaurs are two completely independent branches, akin to the relationship between turtles and crocodiles. While both belong to the reptile class, their appearances are clearly different, and they also have different ancestors and origins. Dinosaurs could not fly until the theropod dinosaurs evolved. Thus, for a long time before that, pterosaurs were the only reptiles capable of flight.

Pterosaurs and dinosaurs are two completely independent branches.

In recent years, humans have finally taken the first steps in unraveling the mystery of the origins of pterosaurs.

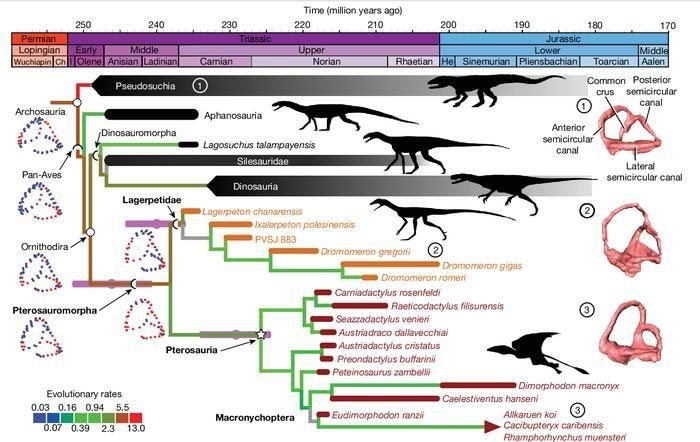

In a study conducted in 2021, researchers analyzed fossils using modern scanning technologies and confirmed that among all known ancient creatures, the closest relatives of pterosaurs are a group called Lagerpetids. These creatures were wingless but bore characteristics indicating they were gradually adapting for life in the skies.

3D scan images revealed they had anatomical features similar to those of both lizards and pterosaurs, helping scientists establish the relationship between these ancient creatures and create the evolutionary tree of pterosaurs.

Lagerpetids lived during the Triassic period, the first period of the Mesozoic Era, with the earliest Lagerpetid fossils dating back 236 million years—about 10 million years earlier than the earliest pterosaurs.

The 2021 study indicated that they had inner ear features similar to those of pterosaurs. These characteristics also resemble those found in birds’ inner ears (similar in morphology but with different evolutionary origins). These features are crucial for body balance and head stability, which are essential for developing the ability to fly.

The similarity in inner ear shape suggests Lagerpetids are closely related to pterosaurs.

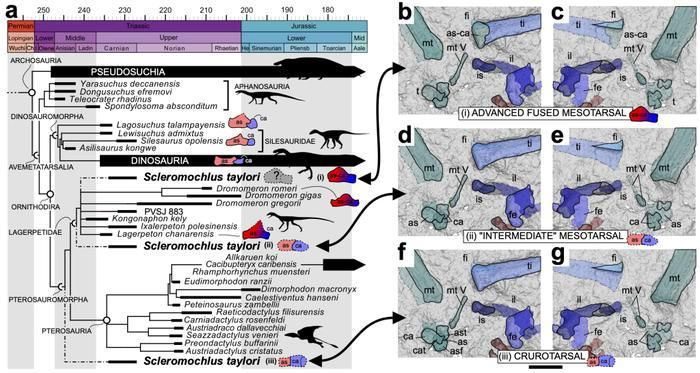

In October 2022, scientists further confirmed this hypothesis. They analyzed fossils of a species called Scleromochlus, which lived in Scotland 235 million years ago.

In the early 20th century, fossils of seven Scleromochlus skeletons were discovered in Scotland. However, they were too small and poorly preserved, making them difficult to study. Paleontologist Davide Foffa and his team employed micro-CT scanning to examine these skeletal fossils. They used this technique to create digital 3D models of each centimeter of the skeleton and study Scleromochlus’s anatomy in detail.

Based on the new anatomical findings they observed, they discovered that Scleromochlus could either be the most basal member of the Lagerpetid dinosaur group or a close relative of pterosaurs, or even more closely related to pterosaurs than other Lagerpetid dinosaurs. Although they could not definitively conclude which scenario was correct, the classification position of Scleromochlus is closer to the origins of pterosaurs than other species.

Micro-CT scans and the study of small skeletal fossils indicate that the phylogenetic position of Scleromochlus is uncertain, but closer to the origins of pterosaurs.

Scleromochlus also possessed several intriguing anatomical features. It not only shared overall anatomy with other lizard species but also exhibited similar skull features to later pterosaurs, such as a long, pointed snout.

Scleromochlus, like pterosaurs, could not climb trees. Scientists believe that tree climbing and falling could be the origins of flight. However, Davide Foffa’s research indicates that the skull features and sensory organs of pterosaurs directed them towards true evolutionary flight from the outset, while anatomical structures related to tree climbing, such as gripping bark and large, sharp claws, did not exist.

Scleromochlus, like pterosaurs, could not climb trees.

In some ways, the study of Scleromochlus has raised more questions than answers. When did pterosaurs develop their wings? Why did they evolve these sensory balance organs? Nevertheless, this study may narrow the gap between pterosaurs and their closest relatives, Lagerpetids, while providing a more specific timeframe (around 235 million years ago) to investigate fossils related to the origins of pterosaurs. Although the stories of Scleromochlus are not yet complete, they lead us to a new chapter in the tales of the origins of pterosaurs.