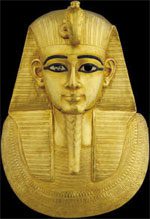

A series of newly discovered medieval Arabic texts has revealed that the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII was a brilliant mathematician, chemist, and philosopher, authoring numerous scientific works. She also held weekly meetings with a group of experts to exchange ideas.

A series of newly discovered medieval Arabic texts has revealed that the Egyptian queen Cleopatra VII was a brilliant mathematician, chemist, and philosopher, authoring numerous scientific works. She also held weekly meetings with a group of experts to exchange ideas.

If historians can verify these claims, the once-renowned queen will no longer be labeled as a promiscuous woman as portrayed by Greek and Roman scholars.

The new revelations are found in a book titled Egyptology: The Missing Millennium, Ancient Egypt in Medieval Arabic Writings, set to be published by the University of London in January. The author, Okasha El Daly, an Egyptologist at the Egyptian Archaeological Museum of the University of London, discovered these medieval Arabic texts and translated and analyzed them based on his knowledge of ancient Egyptian history.

El Daly believes that Arab authors had access to early texts discussing Cleopatra, and even to books authored by her. However, those materials no longer exist. The Library of Alexandria, which housed ancient documents about Egypt, was burned by Islamic forces aiming to destroy all texts predating the Quran.

El Daly cites the earliest Arabic document mentioning Cleopatra, written by the scholar Al-Masudi, who died in 956 AD. In his book titled Muruj, Al-Masudi describes Cleopatra as follows: “She is a sage, a philosopher, who always esteemed scholars and enjoyed exchanging ideas with them. She also authored books on medicine, charms, and cosmetics.”

.jpg) Medieval Arab authors such as Al-Bakri, Yaqut, Ibn Al-Ibri, Ibn Duqmaq, and Al-Maqrizi also recounted their impressions of the queen’s construction projects. In fact, an Arabic book by the Egyptian monk John of Nikiou states that the queen’s construction projects in Alexandria were unlike any previous works. Conversely, another Arab historian, Ibn Ab Al-Hakam, claimed that one of the greatest constructions of the ancient world—the Lighthouse of Alexandria—was indeed built by Cleopatra.

Medieval Arab authors such as Al-Bakri, Yaqut, Ibn Al-Ibri, Ibn Duqmaq, and Al-Maqrizi also recounted their impressions of the queen’s construction projects. In fact, an Arabic book by the Egyptian monk John of Nikiou states that the queen’s construction projects in Alexandria were unlike any previous works. Conversely, another Arab historian, Ibn Ab Al-Hakam, claimed that one of the greatest constructions of the ancient world—the Lighthouse of Alexandria—was indeed built by Cleopatra.

El Daly remarked, “It was not just a lighthouse guiding ships but also a great telescope, with large lenses capable of igniting enemy ships attempting to attack Egypt.”

Other sources suggest that Cleopatra created a formula to prevent hair loss and even researched gynecology. Authors Ibn Fatik and Ibn Usaybiah noted that she conducted experiments to determine the stages of human fetal development in the womb.

“All current information about Cleopatra stems from her enemies. The Romans despised her and sought to create a lascivious image of the petite woman,” El Daly commented. He also pointed out that coins bearing her likeness depict her as a very ordinary woman, not conventionally beautiful.

However, Mary Lefkowitz, a professor at the Wellesley College’s Classical Studies Institute, disagrees with the notion that the Romans intentionally tarnished Cleopatra’s image. “In fact, the Romans greatly admired Cleopatra, although they feared her power,” Lefkowitz stated.

Lefkowitz further added that Cleopatra was a royal name in the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt, so it is possible that Arabic histories referred to another queen of the same name. Nevertheless, Lisa Schwappach, at the Egyptian Museum in California, believes it is highly likely that Queen Cleopatra VII was a scientist rather than a promiscuous woman.

Lefkowitz further added that Cleopatra was a royal name in the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt, so it is possible that Arabic histories referred to another queen of the same name. Nevertheless, Lisa Schwappach, at the Egyptian Museum in California, believes it is highly likely that Queen Cleopatra VII was a scientist rather than a promiscuous woman.

“At the very least, Cleopatra was involved in medicine by supporting the Hathor temple in Dendera, where women often went for physical and mental healing,” Schwappach stated.

She added, “Cleopatra was educated in science, and it is not surprising that she supported scholars and exchanged thoughts with them. She could stand alongside them not only due to her social status but also because of her intellect and knowledge.”

Minh Thi