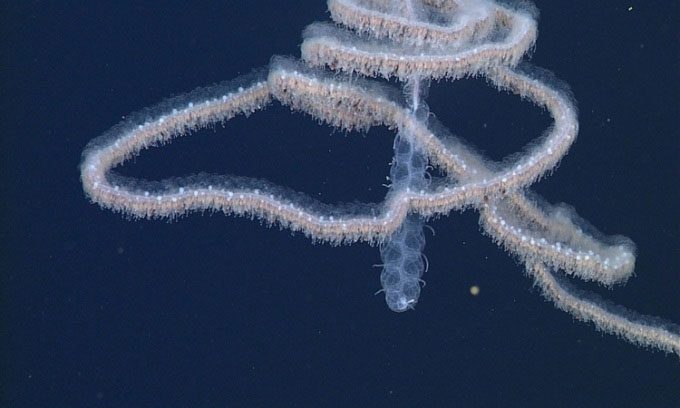

Siphonophores are extraordinary animals composed of many individual organisms known as zooids. Each zooid has a distinct function, despite being genetically identical.

Siphonophore (Tube Jellyfish) belongs to the class Siphonophora and can be found in all the world’s oceans, primarily feeding on small crustaceans, paddle-footed crustaceans, and fish. This peculiar marine creature can grow longer than a blue whale, the largest animal on Earth, reaching lengths of up to 46 meters, according to Live Science.

Siphonophore is a collection of many genetically identical individual organisms. (Photo: MBARI)

There are about 175 species of siphonophores living in the deep seas of all oceans. Many siphonophores appear like long threads, while some species, such as the Portuguese Man o’ War (Physalia physalis), resemble jellyfish and possess venom.

Although siphonophores may seem like solitary animals, they are actually a colony consisting of individual organizations called zooids, each performing a specific function. Some zooids specialize in capturing prey and digesting food, while others enable the colony to reproduce or swim. A zooid cannot survive independently since they are specialized in performing a single function, thus relying on each other to form the body. Siphonophores develop from a zooid that hatches from a fertilized egg. This first zooid develops a growth region, from which new zooids emerge. Siphonophores reproduce asexually to produce more and more zooids.

Siphonophores consume a variety of small marine animals, including plankton, fish, and crustaceans. Those zooids that use venom to capture prey have tentacles equipped with stinging cells that paralyze. To hunt, they extend their stinging tentacles, immobilizing their prey before pulling the food into their mouths. Marine biologists recorded a siphonophore feeding off the west coast of Australia in 2020. They discovered a giant siphonophore (Praya dubia) measuring 45.7 meters long creating lethal spirals to trap unsuspecting prey.

Many siphonophores also exhibit bioluminescence, producing light through chemical reactions to attract prey. While most species emit green or blue light, one siphonophore from the genus Erenna is the first invertebrate known to glow red. Red bioluminescence is extremely rare because the shorter wavelengths of green and blue light travel farther in the ocean and are evolutionarily more advantageous for marine animals. According to a paper published in 2005 in the journal Science by marine biologist Steven Haddock from the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, the red light may help attract fish, as they mistake the red glow for the bioluminescent algae found in the stomachs of prey such as paddle-footed crustaceans.

Siphonophores often become prey for sea turtles or larger fish. However, some species can use their stinging tentacles for defense against predators. They are also targets for tiny transparent crustaceans known as Phronima, which can bite through siphonophores to live inside their bodies, causing them to slowly die.