Scientists have researched an alloy made from chromium, cobalt, and nickel (CrCoNi) and measured the highest hardness among all materials.

The CrCoNi alloy is not only malleable but also exhibits increased hardness at lower temperatures, in contrast to most other metals. The research team, led by experts from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, published their groundbreaking findings in the journal Science on December 2nd. “When you design construction materials, they need to be hard, malleable, and tough to break”, stated Easo George, co-lead of the project. “Typically, these characteristics offset each other. But this material has it all. Instead of becoming brittle at lower temperatures, it becomes stronger.”

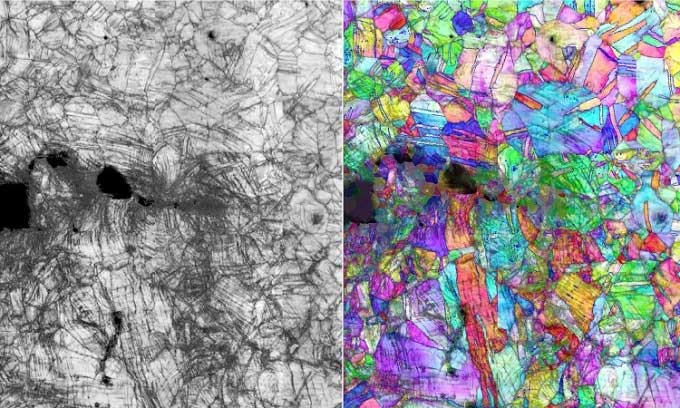

Crystal structure of CrCoNi viewed under a microscope. (Photo: Berkeley Laboratory)

CrCoNi is a small group within the category of metals known as high-entropy alloys (HEA). All alloys used today contain a large amount of one element, with additional elements in lower ratios, but HEAs contain constituent elements in roughly equal amounts. This balance contributes to high strength and ductility under pressure.

The hardness of the new material approaches liquid helium temperatures (-253 degrees Celsius), reaching 500 MPa-Sqrt (a measure of hardness). For comparison, the hardness of silicon is 1, that of aluminum frames in passenger aircraft is 35, and some of the best steels are around 100. Thus, a hardness of 500 is remarkable, according to co-research lead Robert Ritchie, a scientist working in the Materials Science Division at Berkeley Laboratory.

The research team began experimenting with CrCoNi and another alloy containing manganese and iron (CrMnFeCoNi) nearly a decade ago. They created alloy samples and then lowered their temperature to near that of liquid nitrogen (about 77 Kelvin or -200 degrees Celsius) and discovered their impressive hardness. They spent another 10 years testing at various temperatures because setting up the laboratory and recruiting researchers who could understand what was happening at the molecular level was no easy task.

Ritchie and George started experimenting with CrCoNi and another alloy also containing manganese and iron (CrMnFeCoNi) almost a decade ago. They produced samples of the alloy and then reduced the temperature of the material to near that of liquid nitrogen (-200 degrees Celsius), uncovering their impressive hardness and strength. An additional 10 years were spent continuing tests at various temperatures of liquid helium due to the challenges of finding a laboratory capable of performing pressure tests in a controlled environment as well as recruiting a team equipped with the necessary tools and experience to analyze what happens within the material at the molecular level.

Using techniques such as neutron diffraction, backscattering electron microscopy, and electron transmission microscopy, Ritchie, George, and colleagues at Berkeley Laboratory, the University of Bristol, Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, and the University of New South Wales examined the crystal lattice structure of CrCoNi samples that had fractured at room temperature and -253 degrees Celsius. Images and atomic maps from these techniques revealed that the hardness of the alloy is due to a trio of dislocation obstacles acting in a specific sequence when force is applied to the material. The CrMnFeCoNi alloy was also tested at -253 degrees Celsius and showed impressive results, but did not achieve the same hardness as the CrCoNi alloy.

Now that researchers have a better understanding of the internal mechanisms of CrCoNi, this alloy and other HEAs are closer to being utilized in special applications. Although producing these materials is costly, they can be applied in situations where harsh environments could destroy conventional metal alloys, such as in the extreme cold conditions of deep space.