Scientists have recently announced a species of eagle believed to be the largest that ever existed.

The Eagle Specializing in Hunting Giant Birds

This “monstrous bird” is a predator similar to modern descendants but has eating habits akin to vultures.

The giant eagle and the nightmare of the Moa bird.

This giant bird is known as the Haast’s Eagle, which hunts, grasps, and pierces its prey with its sharp talons. They even dive into their prey to enjoy a meal of organs.

For a long time, scientists have debated whether this eagle species was a predator like modern eagles or a scavenger like vultures. Its feet and talons resemble those of eagles, while some other features are similar to vultures.

Current techniques have allowed them to model and compare it with living bird species. After analysis, it was concluded that they were predators like eagles while also feeding like vultures.

The Haast’s Eagle lived in New Zealand, weighing up to 15 kg with talons reaching 9 cm and wingspans of up to 3 meters.

One of its main prey was the Moa, a large, flightless bird that was once abundant on the islands before becoming extinct around 800 years ago.

One of the reasons for the extinction of these two bird species was the arrival of the Maori people on the island, who hunted the Moa and destroyed their habitats. The indiscriminate hunting by humans inadvertently led to the eagle losing its food source and becoming extinct.

Like its predator, the Moa was also a giant bird. They could reach heights of up to 3.7 meters when stretching their necks and weighed around 230 kg.

Searching for Answers About When the Haast’s Eagle Arrived in New Zealand

New Zealand has always held a crucial place in scientists’ understanding of species extinction. When Western scientists first encountered the Moa, the idea that species could go extinct had only emerged a few decades earlier. Their bones quickly attracted researchers. Haast himself founded a museum and compiled its initial collection by exchanging Moa fossils for various archaeological and zoological curiosities.

New Zealand also harbors bizarre species, most famously the flightless kiwi. The Moa fossils helped establish the idea that New Zealand was a lost world, a place where ancient creatures kept their distance from the rest of the world, surviving mass extinction events. In 1990, a television series depicted New Zealand’s islands as “Moa’s Ark,” popularizing an enticing name for the age-old model of how its bird-filled ecosystem formed.

By the late 1990s, scientists noted that around 25 million years ago, there was a period where geological and climatic changes might have submerged most of New Zealand underwater. Such a scenario could have wiped out most species on the island. However, this theory, known as Oligocene Drowning, faced opposition from some scientists, sparking a lively debate.

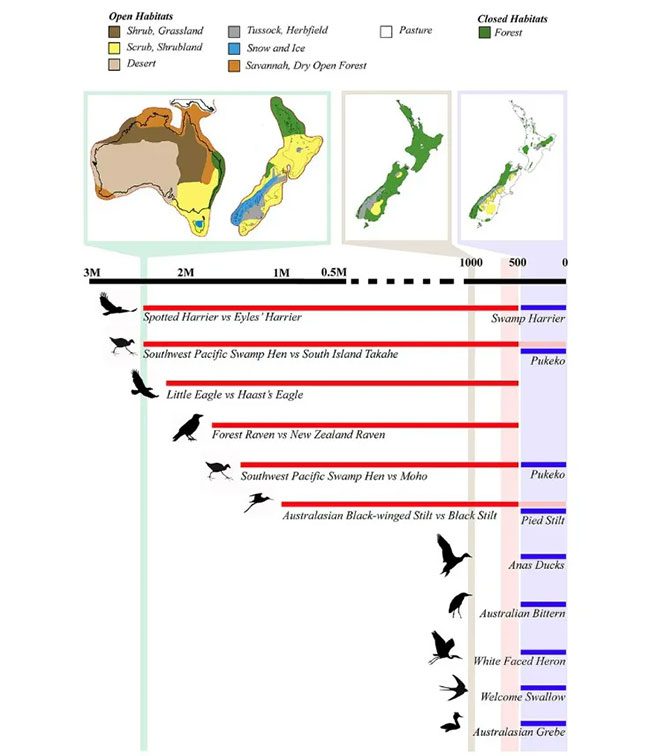

Twice, “bird waves” have reached New Zealand (marked in red and blue).

Fortunately, new technologies have emerged to answer these questions. Starting with extracting and sequencing DNA from fossils, then comparing ancient DNA with modern genomes, and creating a family tree of the evolutionary relationships between living and extinct species. This will help pinpoint exactly when the two species diverged from their common ancestor, providing valuable data to resolve the geological history of New Zealand.

In 2005, a team of scientists published a paper comparing DNA sequences extracted from two Haast’s Eagle fossils with the genomes of 16 modern eagles. They determined that the closest living relatives of this extinct bird include species from Australia, just as expected. The genomic data indicated that the family tree diverged within the last few million years. Subsequent analysis suggested a divergence time of around 2.2 million years ago.

Thus, the hypothesis known as “Oligocene Drowning” has part of its answer: The eagle appears to have arrived after the projected drowning period. However, some analyses of other New Zealand species indicate divergence times of tens of millions of years. In this case, some species survived the Oligocene.

By 2014, geological evidence had convinced most scientists. It was indeed true that most of New Zealand had been submerged; however, some land—about 20%—remained above water, and species like the Haast’s Eagle were newcomers.

New Mysteries Revealed

Genetic analyses have revealed a new mystery, something even scientists did not consider. They often compared the extinct bird with the wedge-tailed eagle, the largest remaining raptor in Australia. It was an obvious candidate for the closest relative of the giant eagle. However, the genes indicated a closer relationship with the grass eagle and the little eagle, both of which weigh only about 1 kg.

This discovery shows that the Haast’s Eagle underwent a remarkable size leap compared to its closest relatives: increasing 15 times in just 2 million years. That is an astonishing rate of change.

The small eagles, weighing only 2 pounds, are among the closest living relatives of the giant Haast’s Eagle.

Thus, it is possible that all three eagles shared a common unknown ancestor with a size somewhere in between. Its descendants may have evolved in various directions.

Another note is that researchers suggest other predatory birds on the island only hunted the smallest birds. However, the Moa species varied in size but were too large. Therefore, only the largest eagles would have been able to hunt them.

They are currently focusing on comparing the genomes of different eagle species to precisely identify which genes changed to allow the Haast’s Eagle to grow so rapidly.

In addition to the Haast’s Eagle, New Zealand’s ecological history has also unveiled new insights. Another extinct New Zealand bird, known as Eyles’s Harrier, was the largest raptor known in history. It also appears to have evolved from a smaller bird species. According to the latest reports, the closest relative of the Eyles’s Harrier is nearly five times smaller. Both bird species may have diverged from their common ancestor around 2.4 million years ago, close to the divergence time of the Haast’s Eagle.