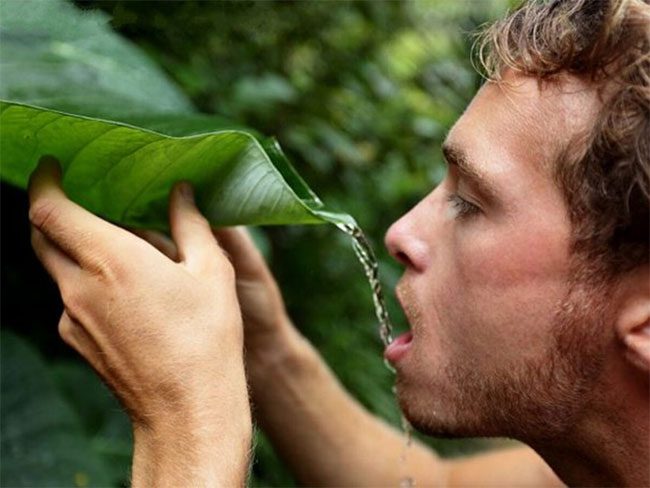

If you collect rainwater on rainy days, you might think that these clear and fresh droplets are just like the treated water that flows from your home tap. But is rainwater really safe to drink?

Chemicals in Rainwater

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), various contaminants can exist in rainwater, such as bacteria, viruses, parasites, dust, smoke, and other chemicals.

Rainwater cascading down from rooftops can also contain traces left by animals, like bird droppings, and if the drainage pipes are old, materials like asbestos, lead, and copper may also accumulate in your storage tank.

If rainwater is collected in an open tank, it can also become filled with insects and decaying organic matter, such as leaves.

Rainwater contains many contaminants.

However, the levels of these pollutants can vary significantly depending on where you live, and the risk of illness largely depends on the amount of rainwater you consume.

If you have a clean rainwater harvesting system and properly disinfect the rainwater, either chemically or by boiling and distilling it, most impurities can be removed.

Nevertheless, there is a new risk associated with drinking rainwater caused by human activity. In a study published in August 2022 in the journal Environmental Science & Technology, scientists found that global rainwater contains harmful levels of PFAS exceeding health regulations. This means that rainwater is definitely not safe to drink, especially if it is not treated thoroughly.

According to Ian Cousins, an environmental chemistry expert at Stockholm University in Sweden, PFAS is a general term for over 1,400 man-made substances and chemicals that have been used in a variety of products, including textiles, firefighting foam, non-stick cookware, food packaging, artificial turf, and guitar strings…

However, current understanding of the biological impacts of rainwater primarily relies on studies of four perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) — a subgroup of PFAS, which includes perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS), perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), perfluorohexanesulfonic acid (PFHxS), and perfluorononanoic acid (PFNA).

Previous research has shown that at high exposure levels, these chemicals are extremely toxic and can cause a range of health issues, including various types of cancer, infertility, pregnancy complications, developmental problems, immune system disorders, and diseases of the intestines, liver, and thyroid. Additionally, as noted by scientist Cousins, they can also reduce vaccine efficacy in children.

This evidence has led to the banning or significant restriction of PFAAs and most other PFAS over the past 20 to 30 years, except in some Asian countries.

Health guidelines surrounding PFAS have also been revised to reflect the toxicity of these chemicals. For example, in the U.S., the safe exposure level for PFOA set by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is now determined to be less than 37.5 million times lower than previously established levels.

PFAS are not easily broken down, which means they persist in the environment long after being produced, and their toxicity does not diminish. This has led scientists to nickname PFAS as “forever chemicals.”

Not Safe to Drink

Rainwater is not safe to drink.

In the study, scientists collected data from rainwater samples worldwide. They revealed that PFAS remains prevalent in rainwater across the globe, with levels exceeding the safety standards set by the EPA and similar regulatory agencies in other countries.

According to Cousins, experts had hoped that PFAS levels might begin to decline from now on, but that is not the case. The most notable finding is that PFOA levels in rainwater are at least 10 times higher than the EPA’s safe level at every sampling location on the planet, including the Tibetan Plateau and Antarctica.

Researchers still do not fully understand how PFAS reaches the most remote areas of the world. They hypothesize that PFAS from ocean surfaces is sucked up, returned to the atmosphere, and then transported to other regions, eventually falling back to Earth as rain.

Another research group suggests that PFAS leaks and flows into the oceans, spreading across various regions worldwide. To ascertain the precise cause, scientists plan to expedite testing this hypothesis in the future.

According to Cousins, it is still too early to predict the overall public health impacts of PFAS-rich rainwater globally, but they may already be quietly exerting their influence.

The impact of PFAS is likely to be more significant in developing countries, where millions of people rely on rainwater as their sole drinking water source. Even in some areas of developed countries, like Western Australia, drinking rainwater remains common.

Regardless of whether rainwater is properly treated, there is no guarantee that PFAS will be eliminated. They can also be found at low levels in tap and bottled drinking water, although typically at safe levels.

PFAS levels will eventually decrease as they settle deep in the ocean, but this is a gradual process that may take decades. Therefore, the CDC advises against storing and drinking rainwater, recommending its use only for other purposes, such as watering plants and cleaning objects.