If you are like Einstein, the genius physicist, you will promptly respond to some letters while making others wait. Of course, there are some letters you will never answer.

If you are like Einstein, the genius physicist, you will promptly respond to some letters while making others wait. Of course, there are some letters you will never answer.

At any time, you might find an old letter in your mailbox and decide to respond to it.

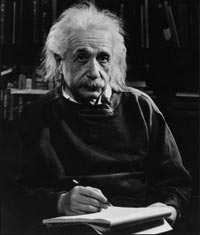

A new study has found that the way Albert Einstein handled correspondence, much like Charles Darwin, follows a pattern similar to modern email communication.

Einstein sent over 14,500 letters. However, he received more than 16,200 and only replied to a quarter of them. Darwin sent over 7,500 letters but only responded to 32% of nearly 6,530 letters he received.

Of course, writing letters takes more time than sending emails, but the mathematical correlation between quick and slow responses is similar, noted João Gama Oliveira from the University of Aveiro in Portugal.

|

| The number of letters sent by Darwin (black) and received (red), and the number of letters sent by Einstein (green) and received (blue). During the last 30 years of his life, Einstein wrote a letter every day. (Nature) |

Among Einstein’s replies, 53% were sent within 10 days. For Darwin, this figure was 63%. However, there were instances where they delayed responses for months. Einstein often began a reply by explaining that he had just discovered this letter, which had arrived over a year ago, while sorting through a mountain of correspondence.

“In the correspondence of both Darwin and Einstein, as well as today’s emails, we find that most responses are made quickly, but sometimes with a significant delay,” Oliveira remarked. “In other words, with both emails and handwritten letters, the response time spans a wide range, and there is no typical value we can point to indicating that response times cluster around a specific point.”

The analysis also indicates that Darwin, who proposed the idea of natural selection in evolution, and Einstein—the father of modern physics—likely prioritized handwritten letters. “Their timely responses to most letters indicate that both were aware of the importance of intellectual exchange,” Oliveira and colleagues wrote.

T. An (according to LiveScience)