A series of new studies on experimental animals and human models are providing the first explanations for why the Omicron variant causes milder illness compared to other variants of SARS-CoV-2.

In experiments on mice and hamsters, Omicron causes less severe illness, typically confined mostly to the upper respiratory tract: nose, throat, and trachea. This variant is less harmful to the lungs, while previous variants often caused lung damage and severe breathing difficulties.

In November, when the first reports of the Omicron variant emerged from South Africa, scientists could only speculate about how it differed in behavior from other variants. All they knew was that Omicron was a particularly alarming combination of over 50 genetic mutations.

Over the past month, dozens of research teams have observed the new pathogen in laboratories, introducing Omicron into cells in petri dishes and spraying the virus into the noses of animals. While the number of infections surged, hospitalizations only increased slightly.

Initial studies on patients indicate that Omicron causes less severe illness than other variants, especially in vaccinated individuals. However, these findings come with many caveats.

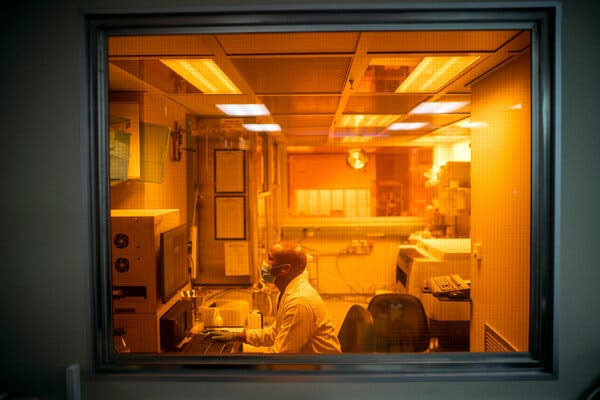

Many studies indicate that the Omicron variant causes milder illness than previous variants. (Photo: Reuters)

Animal experiments can help clarify these ambiguities, as scientists have the opportunity to test the Omicron variant on identical animals living under the same conditions.

More than half a dozen experiments published in recent days all point to the same conclusion: Omicron causes milder illness than Delta and earlier variants of the virus.

On December 29, a group of Japanese and American scientists published a report on hamsters and mice infected with the Omicron variant or one of the earlier variants. According to the study, those infected with Omicron experienced less lung damage, less weight loss, and a lower risk of death.

Many other studies have also reached similar conclusions. The reason Omicron causes milder illness may require anatomical explanations.

Dr. Michael Diamond, a virologist at the University of Washington (USA), and his colleagues found that the concentration of Omicron in the noses of hamsters was similar to levels in animals infected with earlier variants. However, the concentration of Omicron in the lungs was only one-tenth or less than that of other variants.

Omicron causes less lung damage than other variants. (Photo: AP)

Researchers at the University of Hong Kong also made similar findings. They studied tissue samples taken from human airways during surgery. In 12 lung samples, researchers observed that Omicron grew more slowly than Delta and other variants.

These findings will need to be followed up with more in-depth studies, such as experiments with monkeys or examining the airways of individuals infected with Omicron. If the results are thoroughly investigated, they could explain why those infected with Omicron seem to require hospitalization less than those infected with Delta.

Many cells in the lungs carry a protein called TMPRSS2 on their surfaces. This protein may inadvertently assist the virus in entering the cells. However, Dr. Ravindra Gupta, an expert at the University of Cambridge (UK), and his team found that TMPRSS2 does not bind well to Omicron. As a result, Omicron does not infect lung cells as quickly as Delta. A research group at the same university reached a similar conclusion.

Dr. Gupta speculates that Omicron has evolved into a variant specialized for the upper respiratory tract, thriving in the throat and nose. If this is true, it would be more easily spread into the environment through droplets and infect new hosts.