In the late 1700s, geologist James Hutton faced criticism for suggesting that the Earth was not merely 6,000 years old, as was the common belief of the time.

On a June afternoon in 1788, James Hutton stood before a rock outcrop known as Siccar Point on the western coast of Scotland and told the skeptical companions who had sailed with him that Siccar Point was evidence of a shocking truth: the Earth is ancient, almost beyond comprehension.

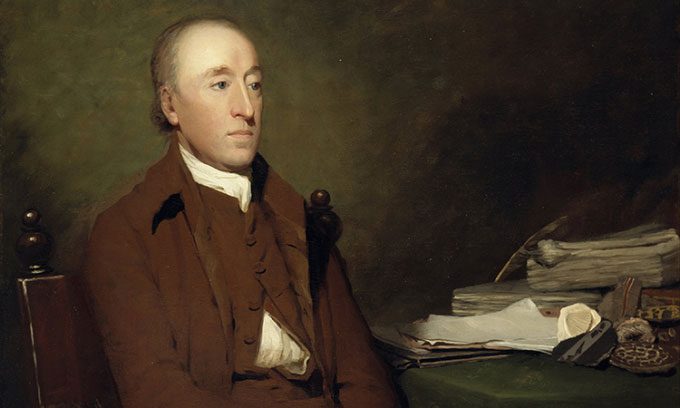

Portrait of James Hutton by artist Henry Raeburn in 1776. (Photo: National Gallery of Scotland)

His ideas were shocking at a time when most natural philosophers (the term “scientist” had not yet emerged) believed that the Earth was created by God around 6,000 years ago. The prevailing notion was that the world had been in a continuous decline since the perfect Garden of Eden. Therefore, the Earth had to be young. The King James Bible even set the date of the Earth’s creation as October 23, 4004 BC.

At Siccar Point, Hutton pointed to evidence for his “Theory of the Earth”: it was the intersection of two types of rock formed at different times and by different forces. The gray metamorphic rocks rose vertically, piercing through the horizontally laid red sandstone that had only recently been deposited.

Hutton explained that the gray rock was originally deposited as horizontal sedimentary layers, perhaps at a rate of about 2.5 cm per year. This process occurred a long time ago. Over time, pressure and heat beneath the Earth’s surface transformed this sediment into rock, and then a force caused the strata to tilt, fold, and become vertical. Hutton stated that this was undeniable evidence that the Earth was much older than the prevalent beliefs of his time.

Stephen Marshak, a geology professor at the University of Illinois, USA, has visited Siccar Point twice. “So much of what we think today about geology stems from Hutton,” he shared with Smithsonian magazine in 2016. For Marshak, Hutton is the father of modern geology.

Siccar Point as seen from the top of the cliff. (Photo: Angus Miller/Geowosystem)

Geological Research by Experience

James Hutton was born into a wealthy family in 1726 in Edinburgh, Scotland, according to ThoughtCo. At the age of 10, Hutton began his studies at Edinburgh High School, where he discovered a passion for chemistry and mathematics. By 14, he attended the University of Edinburgh to study the humanities. He became an apprentice to a lawyer at 17, but his manager deemed him unsuitable for the legal profession. Hutton decided to become a physician to continue his studies in chemistry.

After completing three years of medical training at the University of Edinburgh, Hutton went on to finish his medical education at the University of Paris, later receiving his degree at Leiden University in the Netherlands in 1749. However, he realized that medicine was not truly suited for him.

In the early 1750s, he moved to a large estate inherited from his father in Scotland, where he became a farmer. Here, he began to study geology and developed several unique ideas. By 1765, the method of producing sal ammoniac that he and a partner had developed provided enough income for him to leave farming and pursue his passion for science.

Hutton did not have a formal degree in geology, but his experiences on the farm helped him formulate theories about the formation of the Earth—ideas that were entirely novel at the time. He hypothesized that the interior of the Earth was very hot and that the processes transforming the Earth had been ongoing for thousands of years. He published his ideas in the book The Theory of the Earth in 1795.

Hutton’s ideas received much criticism from most geologists of his time. He was also ridiculed for proposing a theory of Earth’s formation that differed from the Bible. He died on March 26, 1797, in Edinburgh while writing his next book.

Illustration of Hutton conducting field research by artist John Kay. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Hutton did not achieve fame during his lifetime. However, his concept of a constantly changing planet had a profound impact.

In 1830, geologist Charles Lyell rephrased and republished many of Hutton’s ideas in his book Principles of Geology and referred to them as the Uniformitarianism theory. This theory became a crucial foundation for modern geology.

Lyell’s work continued to inspire the renowned scientist Charles Darwin to introduce the concept of an ancient mechanism existing since the early days of the Earth in his famous book The Origin of Species. Hutton’s views indirectly sparked the idea of natural selection for Darwin.

Paleontologists Stephen Jay Gould and Jack Repcheck—the author of the book about Hutton titled The Man Who Found Time—recognized his contributions in liberating science from religion and laying the groundwork for Darwin’s theory of evolution.