Although planets have been observed to be slightly distorted due to the gravitational pull of their parent stars, this is the first time a planet with a perfectly oval shape has been documented.

According to Science Alert, thanks to the ESA (European Space Agency) CHEOPS space telescope, a team of scientists led by Dr. Jacques Laskar from the Paris Observatory and the University of Science and Humanities in Paris (France) has discovered a unique planet named WASP-103b, orbiting the WASP-103 star, which is located 1,800 light-years away from us.

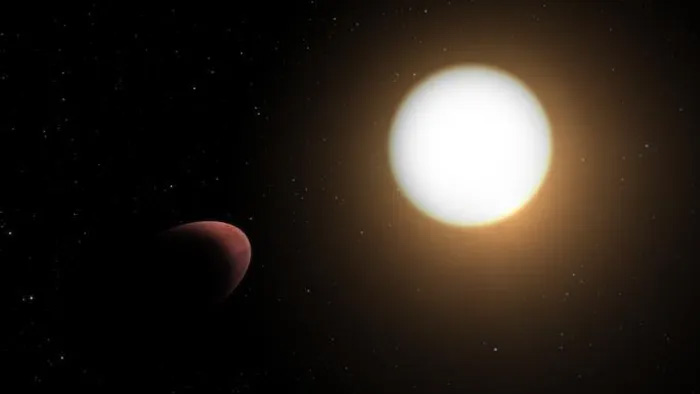

Graphic depicting the newly discovered oval-shaped planet – (Image: ESA).

WASP-103b is classified as a “hot Jupiter”, which refers to a giant gas planet similar to Jupiter, existing unreasonably close to its parent star.

Theoretically, regions near stars with strong gravitational forces, radiation, and stellar winds should prevent gas planets from forming. Despite this, hot Jupiters, which possess powerful gravitational forces like Jupiter, exist in many star systems and often engage in fierce competition with their parent stars to “claim” their atmospheres.

WASP-103b has a mass 1.5 times that of Jupiter from our Solar System and is twice its size, with temperatures reaching up to 20 times hotter. This enormous size is due to the entire planet being inflated by the heat from its star.

Typically, hot Jupiters that are too close to their parent stars tend to spiral inward and will eventually be consumed by the star. However, observations show that WASP-103b is gradually expanding its orbit.

Despite its struggle against the deadly gravitational pull of its parent star, this tug-of-war has resulted in the planet’s unusual shape, causing it to stretch into an elliptical form rather than the traditional spherical shape, and in this case, a perfect oval.

The deformation of a planet will be reflected in a set of parameters collectively known as Love numbers. This seemingly romantic parameter can reflect the characteristics of the planet, as the way a planet deforms is closely related to its material composition, thus providing scientists with a “magic door” into distant worlds that cannot be observed directly.

This research was recently published in the scientific journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.