Scientists are using gene-editing technology to create all-male or all-female litters of mice and are now targeting chickens, aiming to prevent unnecessary killing.

This technique opens a new era for the livestock industry, potentially stopping the mass culling of unwanted male animals, which incurs high production costs and low productivity.

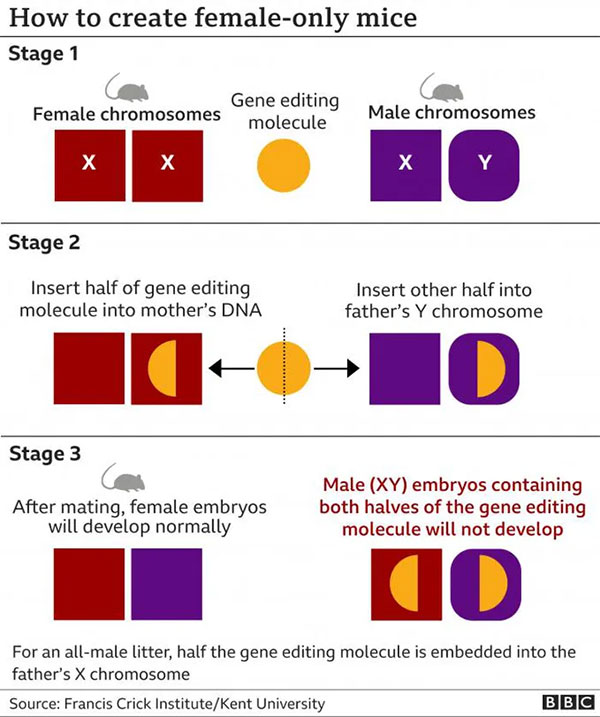

Genetically modified mice have been created to produce only male or female offspring for scientific research. (Image: BBC)

Initially, scientists in the United Kingdom successfully manipulated the sex of mice used in research through gene-editing techniques. The research team stated that they would move on to trials in the poultry industry, which could help prevent the slaughter of millions of innocent male chicks in the UK, culled simply because they… cannot lay eggs.

The UK government is currently considering granting permission for gene editing to be used in domestic livestock.

This innovative technique has been published in the scientific journal Nature Communications, allowing the deactivation of a gene related to embryonic development. The system can be programmed to activate male or female embryos at the very early stage of development, when they consist of about 16 to 32 cells.

Researchers believe that this technique can be widely applied to livestock species raised for protein, and they are discussing with the Roslin Institute to establish pilot studies, marking a pioneering global move in gene editing for livestock.

Dr. Peter Ellis from the University of Kent stated that if the results are permitted to transition from the lab to commercial application, they could have a “far-reaching” impact on animal welfare.

A diagram illustrating the research stages to create mice with the desired sex. (Source: BBC)

“It is estimated that between four to six billion chicks in the poultry industry are killed each year worldwide. In principle, we could establish a system so that instead of having to cull millions of chicks right after they hatch, suffering painful deaths, these eggs simply wouldn’t be placed in an incubator,” said Mr. Peter.

Dr. James Turner from the Francis Crick Institute in London reported that from 25,000 scientific research papers published in the past five years, there is a need for either male or female mice. “The number of mice used in each specific case varies, but often reaches hundreds of thousands. This gene-editing technique for sex selection has had an immediate and valuable impact in scientific laboratories,” Mr. James noted.

An independent report released earlier this week stated that animal welfare must be the focus of any relaxation of regulations allowing gene editing in farm animals.

One of the authors of the report, Mr. Peter Stevenson, a senior policy advisor at Compassion in World Farming, expressed that he is “cautious” about gene editing in general, as it could be misused to manipulate livestock facilities. However, he strongly welcomed its potential application for sex selection in chickens.

“We support its use to improve animal welfare, such as ensuring that hens only produce female chicks, as this would prevent the killing of millions of unwanted chicks in the UK each year.”

Barney Reed from the RSPCA stated that this technology must be tightly regulated. “This is particularly relevant when many of the ‘potential benefits’ being touted are to address animal welfare or environmental issues created by humans,” he remarked.

Dr. Ellis agreed with this viewpoint, stating: “Any potential use in agriculture will require broad dialogue and debate, as well as changes in legislation. Scientifically, there is still much work to be done in the coming years. Further research is needed, first to develop gene-editing toolkits specific to different species, and then to test their safety and effectiveness,” Dr. Ellis added.

How does it work?

The sex of mammals is determined by their sex chromosomes. Females have a pair of X chromosomes—one inherited from their mother and one from their father. However, males have one X chromosome from their mother and one Y chromosome from their father.

The poultry industry may be the first to apply this technology. (Image: BBC)

Using this principle, researchers can prevent the development of XX or XY mouse embryos by deactivating a gene, effectively stopping the embryo’s progression from a very early stage of about 16 to 32 cells.

They can select the sex by embedding one half of a gene-editing molecule, known as Crispr-Cas9, which will deactivate the gene into the mother’s DNA, and the other half into the father’s X or Y chromosome, depending on the desired sex.

The gene can only be deactivated if both halves of Crispr-Cas9 are combined. If one half of the gene-editing molecule from the father is on the Y chromosome of a male, once it combines with the mother’s DNA containing the other half, the resulting XY male embryo will possess both parts of the molecule to deactivate the gene, preventing further development. But all female embryos, which do not inherit the molecule from the father, will develop normally. For a litter of all-male offspring, one half of Crispr-Cas9 is embedded into the father’s X chromosome.