It turns out that the term Crusade does not mean Europeans or individuals who fought in the name of Christ during the Middle Ages. Scholars have long expressed extreme dissatisfaction with this outdated term and proposed abandoning it.

Debunking Common Stereotypes

Most people, upon hearing the name Crusade, imagine knights in iron armor from some medieval monarchy in Europe. Ideally, the Crusaders are envisioned as tall, solemn young white men. However, this established stereotype, like some others in history, has been debunked by geneticists. Experts have demonstrated that the widely accepted concept that “Crusaders means Europeans” is not true.

According to Wikipedia, the Crusades were a series of religious wars, called upon by the Pope and conducted by kings and nobles who volunteered to take up the cross, primarily aimed at restoring Christian control over the Holy Land… The Crusades mainly occurred between the Roman Catholic Church and Muslims, as well as Eastern Orthodox Christians in Byzantium, with smaller campaigns against pagan Slavs, pagan Balts, Mongols, and heretical Christians. Eastern Orthodox Christians also fought against Islamic forces in some Crusades. However, the Crusades were influenced by extensive political, economic, and social factors in Europe: originating from calls for help from Byzantine Empire leaders against the expansion of Islam, with the initial goal of reclaiming Jerusalem and the Holy Land from Muslim control.

The Crusades had some temporary successes, but ultimately the Crusaders were forced to leave the Holy Land.

Crusader Army.

Archaeological Discoveries

In the fall of 2023, off the coast of Israel, a diver accidentally made a remarkable discovery: a medieval sword covered in barnacles, but overall perfectly preserved. Archaeologists carefully cleaned the weapon. It turns out this sword belonged to a knight from the Crusades, and while all media hailed this artifact, very little information is available about it.

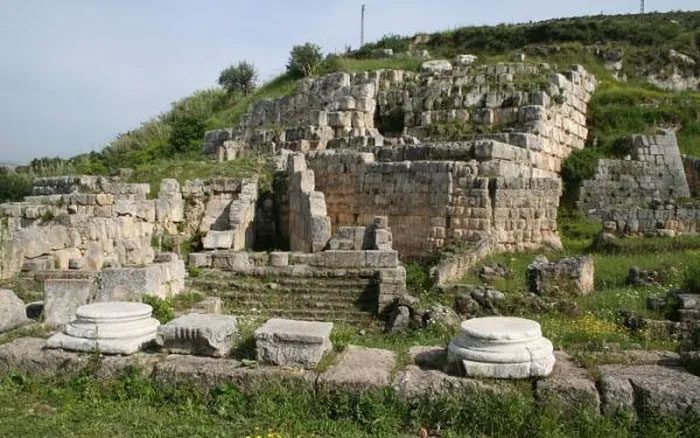

Further evidence came from archaeological discoveries made during excavations in Sidon, located on the Mediterranean coast, 36 km from Beirut, Lebanon, and 34 km from the border with Israel.

The earliest settlements at the site of present-day Sidon emerged in the 4th century BC. However, three centuries later, this city-state achieved real power and glory and was then referred to as Sidon.

By the mid-7th century, the city was one of the provincial centers of the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire, which was conquered by Arabs. The Romans repeatedly attempted to reclaim it. Sidon is mentioned over a dozen times in the Bible, and its name is associated with the firstborn son (also named Sidon) of the Canaanites (the ancient region encompassing Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, western Jordan, and southwestern Syria, also known as the crossroads of Western Asia). This history of Sidon made it one of the main targets of the Crusades in Europe. In 1110, the Crusaders, led by King Baldwin I of Jerusalem and King Sigurd I of Norway, expelled the Arabs from the city and captured it. Sidon remained under Christian control until 1249 when it was destroyed by the Saracen forces of nomads.

In 2019, during excavations at the ruins of the ancient fortress in Sidon, scientists discovered two pits, each containing human remains. A total of 25 male skeletons were identified. Paleontologists began studying this discovery.

However, the identity of the remains was quickly determined. After examining the engravings on belt buckles and some coins found in the grave, archaeologists concluded that these skeletons belonged to Crusader soldiers. Radiocarbon dating established that the remains dated back to the 13th century. At that time, the Crusades were ongoing. Researchers believe the deceased could be “soldiers of Christ,” who defended Sidon against a fierce attack by Saracen armies. All the remains belonged to men, and they showed clear signs of violent death.

Genetic Studies Against Conventional Patterns

9 out of the 25 skeletons were sent for genetic testing. The scientists were meticulous in their work, even examining some data closely, yet the results remained unchanged. DNA analysis showed that one of the skeletons belonged to a middle-aged man from the island of Sardinia. Two of the deceased exhibited genetic markers from Middle Eastern and European ethnicities – immigrants from Anatolia, southern Italy, and Ashkenazi Jews. Two others were from northern Italy or the Basque region.

However, the most interesting part was the genetic makeup of the last four skeletons. It turned out they were remains of individuals with DNA characteristic of Middle Eastern and North African peoples. Genetically, these four men were closest to the inhabitants of Lebanon in the 2nd-6th centuries as well as modern Lebanese people.

Of course, one could assume that during (or after) the bloody battle, Christians and Muslims were hastily buried in the same mass grave. Theoretically, this is possible. However, scientists consider an alternative version of what occurred.

What ethnic group were the main opponents of the Crusaders in the 13th century? To fully understand the situation, a brief excursion into the history of the medieval Crusades is necessary. Thus, from the vast number of documents (both Christian and Islamic) from the 12th-13th centuries that researchers can use, one can identify which ethnic groups were fighting against the Crusader armies at that time.

Therefore, the primary opponents of “the warriors of Christ” were the Bedouin tribes in the desert, as well as those from modern-day Egypt, Iraq, Turkey, and Syria. Naturally, DNA analysis would indicate the presence of genes from these nationalities. However, a group of internationally reputable geneticists found nothing of the sort.

Ancient Ruins of Sidon (now Saida) on the Map of Lebanon.

Typical Mercenaries

And now for the most important point: the four Middle Eastern individuals buried in a pit near Sidon share genetic signs in common with modern Christian populations in Lebanon. Therefore, researchers suggest that the Crusader army was often recruited from local residents in the areas where battles took place.

As for the remains belonging to “mixed-breed” individuals, scientists generally agree that these warriors were likely descendants of European or Middle Eastern visitors from mixed marriages (or regular relationships) with local women. Moreover, it is highly likely that the parents of these men could have been among the first Crusaders who participated in the conquest of Sidon in 1110.

Thus, the long-held idea that “Crusaders were primitive European warriors” has been debunked by geneticists. “The army of Christ” was mostly a temporary armed force, and the Crusades were a good way to make money, to receive feudal allocations from the church when the war ended, or to engage in looting from Muslims.

Consequently, ordinary Crusaders were typical mercenaries, with absolutely no racial or genetic connections. Not all Christians were “Crusaders.” The Crusades were not only conducted against Muslims but also against Jews and even against fellow Christians who shared similar beliefs.

|

The Holy Land is an area located between the Mediterranean Sea and the eastern shore of the Jordan River, often considered synonymous with the Kingdom of Israel as defined in the Tanakh. The term “Holy Land” is also used by both Muslims and Christians to refer to the entire region between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea. Part of the significance of the Holy Land comes from the religious importance of Jerusalem (also known as Yerushalayim in Hebrew, and Al-Quds in Arabic). For Jews, this is where King David established the capital of the united kingdom of Israel, and King Solomon built the First Temple. For Christians, this is where Jesus was crucified, second only to Mecca and Medina in importance. According to the Quran, Jerusalem is a stop in the Night Journey of the Prophet Muhammad. For these reasons, Jerusalem has become an important holy site for all three religions.

Leave a Reply |