Fireworks, also known as firecrackers, are a type of explosive that uses propellant, explosive materials, and special additives to create a magnificent display of colorful lights and diverse shapes, designed to bring communities together during collective cultural activities such as the opening and closing ceremonies of festivals, New Year’s Eve, national holidays, and sporting events at various levels.

As a traditional festive firework with a long history, fireworks have been popular among Eastern cultures, particularly in China, since ancient times. However, today, fireworks have become a global phenomenon and are primarily manufactured in industrial factories.

Firecrackers and fireworks differ only in regional pronunciation, and essentially, they are the same. Some definitions suggest that firecrackers are small handheld explosives while fireworks are launched during celebrations, which is incorrect, as their nature is identical.

The fireworks display is an art form that creates grand and colorful landscapes with rich and diverse shapes. So, when were fireworks discovered by humans?

What led to the creation of this captivating masterpiece in the night sky? As the world prepares to enter 2014, we eagerly await beautiful fireworks displays happening in many places around the globe. In this spirit, we would like to introduce readers to the surprising discovery of fireworks and their development throughout history up to the present day.

The First “Firecracker”

The history of fireworks dates back thousands of years to China during the Han Dynasty (around 200 BC). Some even believe that firecrackers emerged before the invention of gunpowder. The first “firecracker” in history was created when someone accidentally threw hollow bamboo tubes into a roaring fire. The hollow bamboo, filled with air, would expand and increase in pressure as the temperature rose. Eventually, when the pressure became great enough, the bamboo shell would burst, resulting in a loud “pop.” The exploding bamboo, accompanied by the loud noise, is considered the first “firecracker” in history.

The bamboo segments were the first “firecrackers”

In ancient times, sounds that humans had never heard before would frighten both people and animals. The ancient Chinese believed that if strange sounds could scare living beings, they could also drive away evil spirits. Particularly, the Nian monster, known for destroying crops and eating people during the New Year, was feared. Thus, the Chinese developed the tradition of throwing fresh bamboo stalks into the fire during the Lunar New Year to scare away the Nian monster and other spirits, hoping for happiness and prosperity in the new year. Over time, ancient Chinese people began using “bamboo firecrackers” during special occasions such as weddings, coronations, and birthdays. This “bamboo firecracker” tradition continued for over a thousand years for exorcisms and special celebrations.

The Invention of Gunpowder

While the exact timing is uncertain, many historians believe that the first firework mixture (the precursor to gunpowder) was discovered in China during the Sui and Tang Dynasties (around 600 to 900 AD). It is likely that during the quest for immortality, ancient alchemists accidentally mixed substances containing sulfur, potassium nitrate, honey, and arsenic nitrite. Historical records indicate that when accidentally heated, the mixture would ignite violently, emitting a bright light and producing a loud explosion that burned the hands and face of one alchemist.

Ancient Chinese gunpowder

Despite the dangers, these alchemists were fascinated by the mixture and continued experimenting to create more powerful explosions. Although the primitive mixture was not as explosive as modern gunpowder, it could still burn brightly and emit light. The first mixture was named “Yaozhou” (Huo Yao) or “fire medicine” or “chemical fire.” Later, it was discovered that if “fire medicine” was placed inside bamboo tubes and thrown into the fire, it would create a much stronger explosion than merely using fresh bamboo to burn. Thus, the firecracker filled with gunpowder was born.

Over time, it became clear that the key to creating explosive gunpowder was using oxygen-rich nitrate salts. They quickly found ways to increase the nitrate content in the gunpowder mixture, enabling it to ignite faster and produce powerful firecrackers with louder sounds. Eventually, they recognized the drawback of bamboo tubes, as incomplete combustion would produce charcoal, limiting the power of the firecracker. Instead, they used honey and other formulas to create the casing for the firecracker.

Experience showed that the explosive effect varied depending on the shape and structure of the casing. Many types of firecracker casings were made from different materials and shapes, including bamboo tubes, wooden blocks, or metal pipes. When detonated, the firecracker created significant air pressure, causing the casing to explode and scatter in multiple directions. When placed in an open-ended tube, the gunpowder would ignite and shoot out large flames along with thick smoke.

Image of “Flame Spear”

The Chinese gradually became aware of the powerful destructive capabilities of gunpowder in explosive devices. By the 10th century, they began using gunpowder for military purposes, creating explosive weapons such as crude bombs and “fire arrows” (bamboo tubes filled with gunpowder attached to arrows, which were then lit and shot at enemies). However, these early weapons were primarily intended to create loud noises to intimidate the enemy rather than cause lethal damage.

Ultimately, the use of explosive weapons for intimidating enemies transitioned to breaching fortifications and destroying enemy forces. In addition to using “fire arrows” and crude bombs, they also developed the “Flame Spear.” A bamboo tube, open at one end, was filled with gunpowder and attached to the tip of a spear. When ignited, the bamboo would emit a powerful and long flame, akin to a primitive flamethrower. Later, fragments of stone, metal, and broken ceramics, even arrows, were added to the “Flame Spear” to enhance its destructive capability. By the 11th century, the nitrate ratio in the gunpowder mixture was increased to 75%, with the remaining 15% charcoal and 10% sulfur (similar to the composition of gunpowder used today).

Chinese cannonball

With the rapid development of gunpowder, fireworks underwent significant improvements. Instead of using bamboo tubes as casings, they were replaced with sturdy paper to encase the gunpowder. A strip of silk was also inserted inside, leading outside to serve as a fuse, allowing for controlled timing of the explosion. Another variant of fireworks, known as “ground rat,” was discovered around the year 1200 AD. It consisted of a paper firecracker with one end open, containing gunpowder and a rat affixed to a wooden body. Similar to the “Flame Spear,” when ignited, the firecracker would explode and launch the rats inside into the air. The “ground rat” was quickly implemented in military tactics to intimidate enemies and disrupt horse herds.

This was the first model of a rocket. Civilian firework developers adopted this method to launch fireworks, creating bright explosions in the sky. These are considered the first fireworks.

Use in Warfare

From the original Flame Spear, the development of cannons began. Gunpowder was mixed with small stones or spearheads, rolled into spherical shapes. The “projectile” launched from the cannon’s barrel, propelled by the explosive pressure, carried small weapons inside, causing significant damage to the enemy forces. The first cannons were made from bamboo tubes, which were later replaced with metal tubes to withstand the immense pressure of explosions. At this stage, the use of gunpowder in military applications spread throughout Asia and the Middle East. By the 1200s, cannons and rockets were utilized in the Mongol conquests across Asia.

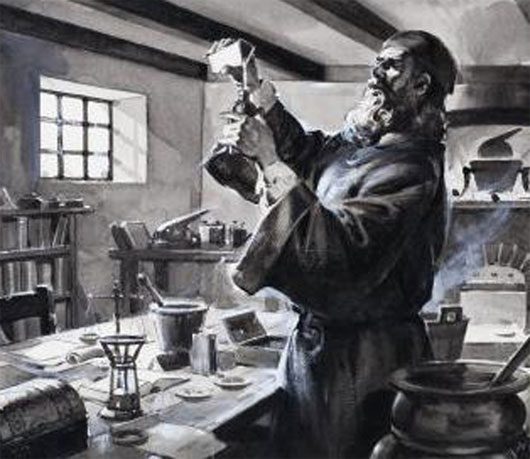

Monk Roger Bacon (1214-1294) was the first to study gunpowder in Europe

Around the mid-13th century, gunpowder began to spread to Europe through diplomats, explorers, and missionary monks. The Dominican and Franciscan monks were pivotal in introducing gunpowder to Europe. Monks returning from China brought gunpowder back to Roger Bacon, a Franciscan monk and professor at Oxford University. Bacon became the first European to study and document gunpowder. He recognized that nitrate was the source of the terrifying sound when gunpowder exploded. He began to refine the quality of natural nitrate to create larger explosions. In one of his writings, Bacon remarked that this weapon caused significant destruction and would revolutionize military warfare.

Cannons used in Europe

Based on Bacon’s research, European scientists worked to develop a much more powerful type of gunpowder. Larger, more powerful cannons were created to propel massive iron balls over great distances. This new weaponry marked the end of medieval-style warfare. Metal armor could be pierced by cannonballs, and the walls of fortresses could be destroyed by cannon fire. Soon after, hollow cannonballs filled with gunpowder and a fuse were designed to create an additional explosion upon reaching the target.

Gunpowder became widespread in the arms race among European nations. Gunpowder factories, known as powderworks, were established in each country to supply large quantities of gunpowder to the military. In these factories, mules and hydraulic power were used to compress and mix large stones to produce a uniform gunpowder product. After victorious battles, armies would often aim their cannons and rockets skyward to create aerial explosions accompanied by the cheers of soldiers, displaying their might.

From 1400 to 1600, advancements in metallurgy led to the creation of more powerful cannons, as well as smaller firearms known as “handguns”. Though firearms still lacked the accuracy and reliability compared to modern guns, they represented a significant advancement in military science over the crude weapons that preceded them, such as spears, swords, and bows. Ultimately, European weapon technology surpassed that of China.

The Flourishing of Fireworks

Marco Polo (1254-1324) – instrumental in bringing fireworks from the East to Italy

While European nations raced to apply gunpowder in military applications, the Italians were captivated by fireworks that explorer Marco Polo brought back from the East in 1292. During the Renaissance in Europe (1400 to 1500), Italians began to develop fireworks into a true art form. This creative period saw the first manufacturing of many types of fireworks. Military rockets were modified by adding metal powder and charcoal to create explosions that produced golden and silver sparks in the sky. The Italians invented the firework shell (a multi-shaped explosive containing materials inside) and launched them to great heights (the Chinese also created shells but were limited to spherical shapes).

However, the most stunning fireworks displays depended on how ground-based launchers were arranged to create the most beautiful effects. Open-ended firework tubes placed on a wheeled wooden frame could rotate while performing, creating sparks that shot out in a circular pattern like a fountain of light. Designers arranged the tubes in various shapes on the ground to create aesthetically pleasing scenes. Fireworks displays generated excitement and captivated crowds during festivals. Quickly, fireworks became an entertainment staple across Europe during religious ceremonies and special occasions.

Fireworks displays grew larger and more complex, involving carpenters, welders, builders, and artists to create beautiful arrangements. Fireworks experts discovered that when fireworks were placed on floating platforms on water, the shimmering light of the explosions would reflect on the surface, creating dazzling visual effects for spectators. From the 1530s, those who lit the fireworks were called “green men” because they covered their faces with soot and wore clothes adorned with leaves to shield themselves from sparks emitted by the fuses.

During the 1500s to 1700s, the most popular firework shape was that of a dragon. When lit, explosions from its mouth created the illusion of a real dragon breathing fire. Performances often depicted two dragons breathing fire against each other.

Fireworks display on the River Thames, London

By the 1730s, fireworks officially became public displays for everyone in England, not just for royalty. People from across Europe flocked to amusement parks in England to enjoy spectacular fireworks displays. Later, fuses were linked together in a chain to create a continuous series of explosions called “quick match,” leading to various performance scenarios. Displays often depicted images of famous characters printed on silver paper.

Modern Fireworks Today

In the 1600s, migrants from Europe to America also brought fireworks to continue using them for special occasions and to frighten and ward off indigenous people. On July 3, 1776, the day the American Congress announced the Declaration of Independence, the public witnessed a spectacular fireworks display organized by the government to celebrate this significant holiday. In the years that followed, fireworks were showcased in America during presidential coronation celebrations or on New Year’s Eve.

Today, the methods of manufacturing and displaying fireworks have been significantly improved with advancements in science and technology. Fireworks are now designed to create more beautiful and vibrant shapes, colors, and sounds. Additionally, fireworks are controlled by electronic systems to ensure precise and safe ignition. Various metal powders are mixed with gunpowder to achieve desired colors. Furthermore, they have developed burning particles (stars) to define the patterns of explosions in the sky. These stars, the size of a coin, can be spherical, cubic, or cylindrical, containing a combustible mixture inside. This component determines the shape and color of fireworks when they explode in the air. Today, a typical firework consists of four main components: the shell, burning particles, core, and fuse.

The imagery created by fireworks depends on the arrangement of burning particles inside the shell. If the burning particles are evenly spaced in a circular pattern within the gunpowder, when exploded, they will create an explosion with evenly spaced sparks forming a circle. To create specific shapes in the sky, the number of burning particles and their positions within the gunpowder must be carefully planned, along with their distance from the core, so that when the firework explodes, the burning particles ignite at precise moments and locations, resulting in the desired imagery.

The typical structure of a modern firework

Additionally, there is a type of firework known as multibreak, which has a complex structure with multiple layers. When ignited, these fireworks can explode in 2 or even 3 stages. Multibreak fireworks are set off in a chain reaction to create distinct, consecutive effects, which can vary from soft to bright lights, few sparks to many sparks, and different colors. Some types of fireworks even have the ability to produce unique sounds as the burning particles explode.

The process of fireworks display is meticulously arranged and supported by a computerized system and electronic launch pads, allowing for precise presentation of predetermined images based on various themes. Sound and background music are also employed to enhance the excitement for viewers, resulting in a grand fireworks display complete with visuals and audio.

Conclusion

Over thousands of years of history, from bamboo tubes accidentally thrown into a fire, to cannons originally intended for warfare, traveling across continents and undergoing significant improvements, fireworks have ultimately been transformed into a vibrant and colorful feast for humanity. They have even evolved into a performance art, showcasing various manufacturing and display techniques. Furthermore, we realize that an item closely associated with war, such as gunpowder, can become a masterpiece of art when used correctly. Today, fireworks have become an exciting and lively spectacle that adds to the festive atmosphere during special commemorative occasions.