What is a Nuclear Shelter? What is its history, and how has it evolved over time? Read on to learn more.

It all began in Japan in the 1940s, shortly after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, with images of hibakusha (survivors of the bomb) and cities reduced to ashes appearing in newspapers. Since that time, Japan’s popular culture has been haunted by nuclear bombs, from genbaku bungaku (literature about nuclear disaster) to Godzilla (1954), and the global success of anime masterpieces like Akira (1988) and the works of Studio Ghibli.

Each nation has had a different cultural response to the bomb. In the United States, the Federal Civil Defense Administration (FCDA), established in 1951, set out to reassure Americans that if a nuclear bomb were ever dropped, they could survive. For a decade, this agency went to great lengths to ease public anxiety about the potential for a U.S.-Russia nuclear retaliation through various community education campaigns, guidance on how to avoid bombs in schools, and many other activities.

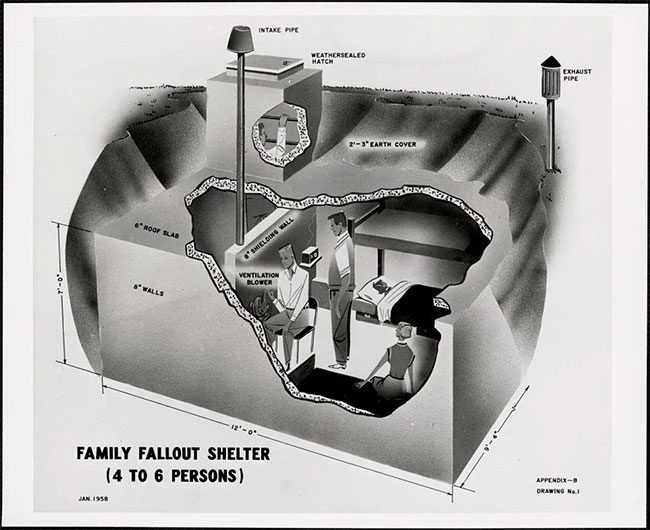

Nuclear Shelter.

Nearly half a billion handbooks released by the FCDA depicted American families hiding in bomb shelters, creating an iconic image in the minds of Americans whenever the topic of nuclear war was raised. These middle-class white families living in suburbs were often illustrated filling their bomb shelters with industrial food supplies or holding their children’s hands as they descended into the bunker, with a strong belief in the government’s promise: as long as the family stayed together, prepared everything, and were ready to respond, they could survive the impending war. Of course, this message was primarily political, serving as a way for the U.S. government at the time to promote traditional values regarding marriage and family.

Furthermore, the survival guides indirectly shifted responsibility away from the state. Placing responsibility on individuals helped America lighten its financial burden and made its nuclear war response policies more appealing—however, with the development of hydrogen bombs and the discovery that a nuclear explosion could cause cancer and heart disease, by the 1960s, the first generation of Americans raised under the shadow of nuclear fears began to doubt the so-called “victory” if a nuclear war were to occur.

This was also the time when the anti-nuclear movement emerged, and with it, the image of families huddling into nuclear shelters, once popular in the culture, became increasingly surreal. In a 1961 episode of The Twilight Zone, a quiet dinner party turns into a horrifying brawl as suburban residents fight for the sole entrance to the town’s bomb shelter. Before the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Saturday Review documented a town hall meeting in Hartford, Connecticut, which descended into chaos when a community member threatened to shoot anyone who approached his shelter.

The image of nuclear shelters continued to evolve, reflecting people’s attitudes toward the upheavals of the Cold War era. As Vietnam became a frequently mentioned name in newspapers by the late 1960s and 1970s, references to family bomb shelters nearly vanished. However, a generation later, with Ronald Reagan’s election as President of the United States, the specter of nuclear war re-emerged.

The image of nuclear shelters continues to change over time.

Nuclear shelters made a comeback—though the image of families joyfully living underground in the 1950s had become a relic of a bygone era. By the 1980s, as the number of nuclear warheads globally exceeded 50,000, the visual culture surrounding shelters became increasingly grim. With the rise of the anti-nuclear movement, the image of shelters resembled nothing more than desperate fortresses in a world where hope was a luxury.

In the UK, where NATO stockpiled cruise missiles in 1979, filmmakers produced two notable works about families living in bunkers waiting for the end of the world. The animated film When the Wind Blows (1986) tells the story of an elderly couple, Jim and Hilda Bloggs, living in the Cotswolds after a nuclear attack turns the UK into a radioactive wasteland. Prior to that, the documentary Threads (1984) depicted the horrors of nuclear war in Sheffield, leaving an entire generation traumatized.

The end of the Cold War also turned nuclear shelters into historical monuments, later becoming centers of nostalgia, as reflected in films like Blast From the Past (1999), “I Love Lucy,” “The Honeymooners,” and the game “Fallout” (1997).

Recent events have brought the image of nuclear shelters back. It is difficult to predict what will happen next. One thing is certain: the image of those shelters still has the power to evoke fear. Will this encourage today’s generation to work together to create a new world where nuclear shelters once again become harmless?