Science has made significant strides in the fight against infectious diseases. Russia during the Tsarist and Soviet eras was one of the most advanced countries in vaccination and protecting its population from infectious diseases.

From History

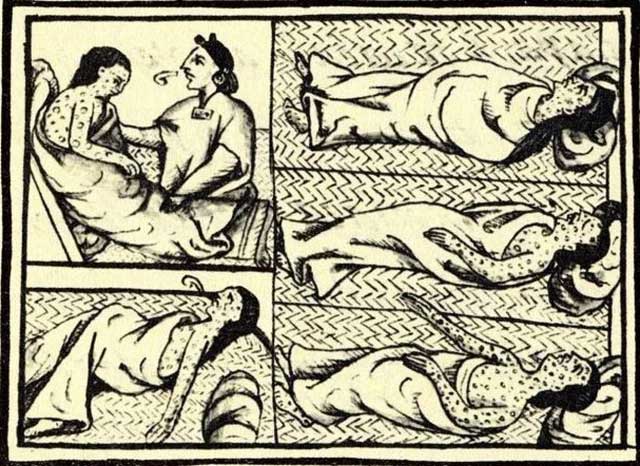

For most of its history, humanity has been powerless against major epidemics. Smallpox affected millions of people each year. This disease killed 20-30% of those infected (90% of infants), often in agony, and survivors were frequently left with disabilities, blindness, and deformities. In Europe, smallpox was responsible for 10-20% of deaths. In America, it was used as a genocidal weapon—clearing “living space” from indigenous peoples.

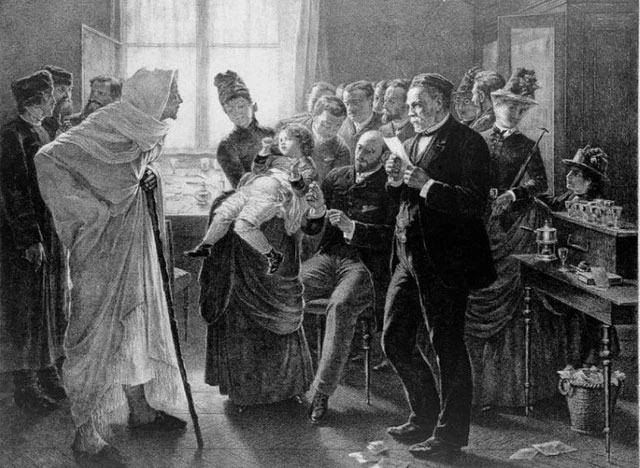

Rabies vaccination at the Pasteur Clinic in Paris. (Source: topwar.ru)

In the 20th century alone, this disease killed over 300 million people. Scientists observed that those who had survived smallpox did not get sick again, paving the way for humanity to create a vaccine. Attempts were made to induce a mild form of smallpox to prevent the risk of severe illness and death. During the Middle Ages, efforts to prevent infectious diseases were known in India and China.

Artificial infection methods were employed—introducing fluid from the pustules of patients with a mild form of smallpox into healthy individuals, or through a method called “nasal insufflation,” where powdered material (often scabs) was inhaled through the nose. Similar folk methods to combat smallpox were used in Africa, Turkey, and Russia.

Smallpox affected everyone—rich and poor, commoners and nobles alike. Thus, in the 18th century, artificial infection became a “trend” among the upper class. When King Louis XV of France died from smallpox in 1774, his grandson Louis XVI was vaccinated. Shortly before another smallpox outbreak, Russian Empress Catherine II sought the help of English doctor Thomas Dimsdale.

In October 1768, Dr. Dimsdale successfully inoculated the Empress and her heir, the future Emperor Paul I, with the smallpox virus. This marked the beginning of mass vaccination in Russia. As a token of gratitude, the English doctor received the title of Baron and a lifetime pension. Catherine even planned a comprehensive vaccination program for the entire population of the empire, but it did not materialize. The state lacked the resources for this, and the population faced a new epidemic.

Defeating Smallpox

For a long time, English doctor Edward Jenner (1749-1823) collected data on smallpox infection rates among farmers. It was noted that cowpox was not harmful to humans, and those who had contracted it rarely fell ill with smallpox. Jenner concluded that it was possible to artificially infect a person with cowpox to protect them from the natural disease.

In 1796, Jenner conducted an experiment—he vaccinated an 8-year-old boy with the cowpox vaccine (from the Latin word vacca, meaning cow). After some time, the boy contracted smallpox, but the disease did not progress. Others also conducted similar experiments, but Jenner was the one who published his method. This method began to be practiced worldwide. In England, smallpox vaccination became mandatory for the army and navy. In Russia, Jenner’s vaccine was first produced by Professor Efrem Mukhin in 1801.

A smallpox patient. (Source: topwar.ru)

Since the material used for vaccination was taken from the pustules (abscesses) of vaccinated children, there was a high risk of secondary infections with diseases such as syphilis. Therefore, in 1852, A. Negri proposed using vaccine material from calves that had been vaccinated. At the 11th World Health Organization Congress, the proposal to eradicate smallpox was put forward by the Soviet delegation in 1958. In 1967, the WHO launched a large smallpox vaccination program, significantly reducing mortality rates, especially among children.

Rabies, Plague, and Cholera

In the latter half of the 19th century, science made significant advancements. In particular, experimental immunology helped study the processes occurring in the body after vaccination. Louis Pasteur (1822-1895)—the renowned French scientist, chemist, and microbiologist, founder of microbiology and immunology—concluded that vaccination methods could be applied to treat other infectious diseases.

Using the model of chicken cholera, this scientist experimentally concluded that a new disease could protect against a subsequent disease. He defined the case of no recurrence of infectious disease after vaccination as “immunity.” In 1881, a French immunologist discovered the vaccine for anthrax. Subsequently, a vaccine was developed to combat rabies. In 1885, the first rabies treatment station was established in Paris.

The second rabies treatment station was founded by Ilya Mechnikov in Russia. In 1886, a “Pasteur station” was established in Odessa. This station became the first bacteriological research center in Russia. Soon after, antirabies-Pasteur stations were created in other cities in Russia. They were established with private funding, so the country could only fully meet its needs in the 1930s. This success allowed Pasteur to combat the wave of criticism against his methods.

In 1888, a special institute for rabies and other infectious diseases was established in the French capital, later named after its creator. The discoveries of Mechnikov and Ehrlich contributed to understanding the nature of individual immunity to infectious diseases. They created a unified doctrine of immunity and were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1908.

Postage stamp honoring the Soviet scientist. (Source: topwar.ru)

In 1892, another student of Mechnikov, Vladimir Khavkin, created the first vaccine against cholera. In 1893, with assistance from Britain, he launched a mass vaccination program against cholera in British India, where the epidemic was rampant. When the plague pandemic began to spread in India, Khavkin developed a vaccine against the plague. The Central Immunology Institute in Mumbai is named after this scientist.

Another Russian scientist, Magdalena Pokrovskaya, developed a vaccine against the plague using live virus. During the Civil War, she investigated outbreaks of plague and malaria in southeastern Russia. In 1934, a vaccine was created. During the Great Patriotic War, Pokrovskaya developed a treatment technology for severe infectious diseases using bacteria—a special virus that destroys bacteria.

The Soviet Victory on the Invisible Front

In 1919, the Soviet government issued a decree mandating smallpox vaccination. After the Civil War ended, when many died from epidemics and weakened immunity (malnutrition, famine, poor sanitary conditions…), the spread of smallpox in the Soviet Union was reduced and ultimately eradicated by the 1930s. In 1925, mass vaccination for children against tuberculosis was initiated. Mass vaccination against polio in the Soviet Union began in 1959, and by the end of 1960, all Soviet citizens under 20 years old had been vaccinated against this disease.

In 1958, a preventive vaccination schedule was implemented and has been in effect in Russia to this day. Initially, the program included vaccines for smallpox, tuberculosis, whooping cough, diphtheria, and polio. Later, vaccines for tetanus and mumps were added to the schedule. Over the past 30 years, several vaccinations have been added to the schedule: against hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae, influenza, and HIB infections.

Today, there are 8 mandatory vaccines in Russia: against hepatitis B, tuberculosis, pneumococcal infections, DPT (against tetanus, diphtheria, and whooping cough), polio, hemophilia infections (for at-risk children), measles and mumps, and influenza. Additionally, there are vaccinations conducted according to medical guidelines, such as for tick-borne encephalitis, plague, rabies, anthrax, typhoid, cholera, etc. Tsarist and Soviet Russia was one of the most advanced countries in vaccination and protecting its population from infectious diseases.