In an era where science and spiritualism intersect, one of the most famous confrontations between magician Harry Houdini and spiritualist Mina Crandon captured public attention. This event not only exposed the conflict between reality and supernatural belief but also reflected a turbulent period when scientific discoveries ran parallel to the desire to reach the afterlife.

On a day in July 1924, O.D. Munn, editor of Scientific American, along with six other scientists, gathered in a stuffy room in Boston. They were not there to conduct a typical scientific experiment but to investigate the supernatural claims of Mina Crandon – also known as “Margery” – a woman with the ability to summon spirits who was causing a stir in American society at the time. This event, featuring Harry Houdini, the world-renowned magician and skeptic of spiritualism, became one of the most notable confrontations between the realms of science and superstition.

Spiritualism spread throughout the Western world during the 19th and early 20th century.

This meeting was the result of a wave of interest in spiritualism, a cultural movement that proliferated throughout the Western world in the 19th and early 20th centuries. This movement not only captivated the public but also attracted the attention of leading scientists such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Believing that science could prove the existence of an afterlife, Doyle even invited Munn to witness Crandon’s abilities to help her win a $5,000 prize for anyone who could demonstrate the existence of supernatural phenomena.

The Age of Science and Belief in the Supernatural

The 19th century is often referred to as the “Age of Science,” when natural laws increasingly shaped human understanding of the world. This was also a period of impressive scientific and medical discoveries, such as James Prescott Joule’s contributions to the Law of Conservation of Energy and the first use of anesthesia in surgery. Yet, despite significant advancements in science, spiritualism persisted and thrived, captivating both the public and intellectuals.

The spiritualist movement began in the 1840s when the Fox sisters in New York claimed to communicate with the dead through knocks and strange sounds. Although they later admitted it was a hoax, at the time, these sèances drew large followings. Spiritualism gradually evolved into a cultural branch, spreading throughout Europe, even encompassing scientists and renowned artists. Such séances became a “laboratory” for exploring spiritual phenomena.

Richard Noakes, a professor at the University of Exeter, remarked that the 19th century was a time when the boundaries between science and spiritualism were not yet clear. Many scientists, in their efforts to understand the afterlife, employed research methods that today might be considered pseudoscientific. Advocates of spiritualism believed that the phenomena of séance were not “super” natural but merely aspects of nature that science had yet to uncover.

The advent of the telegraph laid the groundwork for spiritualism.

The Telegraph and the Desire to Connect Two Worlds

Advancements in communication, especially the invention of the telegraph, created a foundation for spiritualism. Since the telegraph was invented and developed, information could be transmitted over long distances almost instantaneously, something previously unheard of. For contemporaries, if information could travel at the speed of light across vast distances, why couldn’t the living connect with the afterlife in a similar manner?

Consequently, many spiritualists regarded these inventions as evidence that there might be invisible means of communication we had yet to fully understand. They believed that if technology could connect continents, then it could also bridge two worlds, acting as a “telegraph” to communicate with the spirits of the deceased. Séances became a place to test this theory, as mediums often requested “guests” from the other side to respond through knocks or sounds.

The Impact of Photography and the Quest for Evidence of Souls

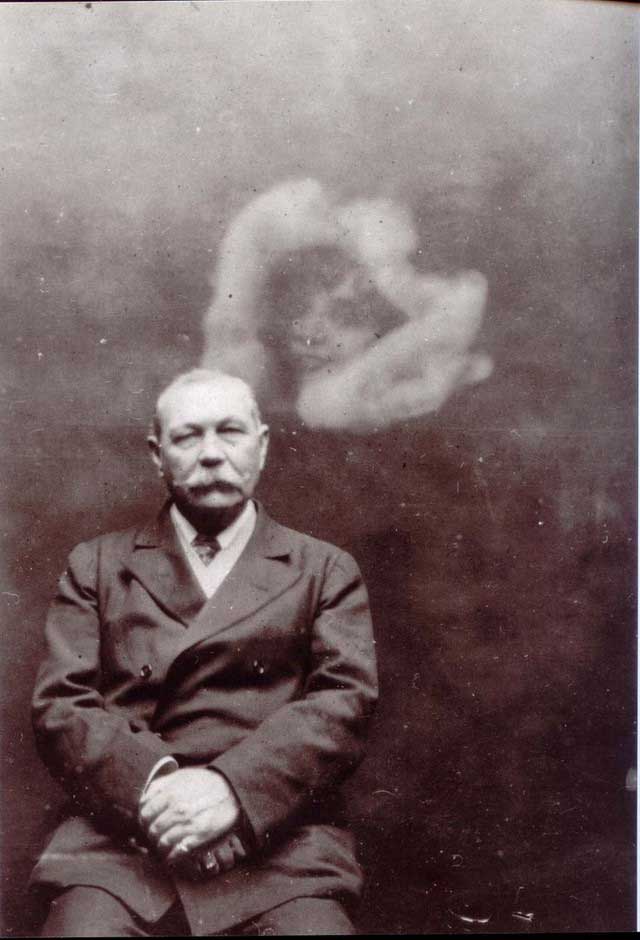

As photographic technology advanced, it was quickly utilized by spiritualists as a tool to “capture” evidence of souls. It was believed that if photography could capture things invisible to the naked eye, it could also capture images of spirits. Many famous “spirit” photographs from the 19th century were created based on this idea, but in reality, photographers used techniques like photo manipulation and lighting effects to create ghostly images.

William H. Mumler and Frederick Hudson were among the photographers who employed these techniques to produce images containing “ghosts.” The appearance of these photographs led the public to have greater faith in photography’s ability to capture evidence of the afterlife. However, with the advancement of technology, “spirit” photographs gradually lost their allure as people began to realize they could be created artificially.

The emergence of these photographs increased public belief that photography could capture ghosts.

The Decline of the Spiritualist Movement and Modern Science

By the early 20th century, the spiritualist movement began to wane as figures like Mina Crandon and other mediums were discovered to be fraudulent. At the Scientific American examination in 1924, Harry Houdini publicly replicated Crandon’s tricks, demonstrating that no supernatural elements were involved. This shattered public trust in Crandon and dealt a significant blow to spiritualism, transforming it from a major cultural movement into a fringe topic within science.

Although enthusiasm for spiritualism faded, the movement had sparked a wave of interest, connecting some of the most curious minds of the era. Those seeking the truth about the afterlife believed that science, rather than mysticism or superstition, would be the pathway to revelation. While today science and spiritualism no longer coexist, the story of scientists pursuing spiritualism is an intriguing part of the history of science. Thus, the ghosts of the past should not be forgotten but understood, so we can reflect on the past and the world around us with openness and tolerance.