Few people realize that, in addition to mummies and pyramids, ancient Egyptians left behind another very special legacy for today: taxation and principles of administrative management.

The ancient Egyptian civilization developed the world’s first tax system around 3000 BC when Upper and Lower Egypt united to form the First Dynasty.

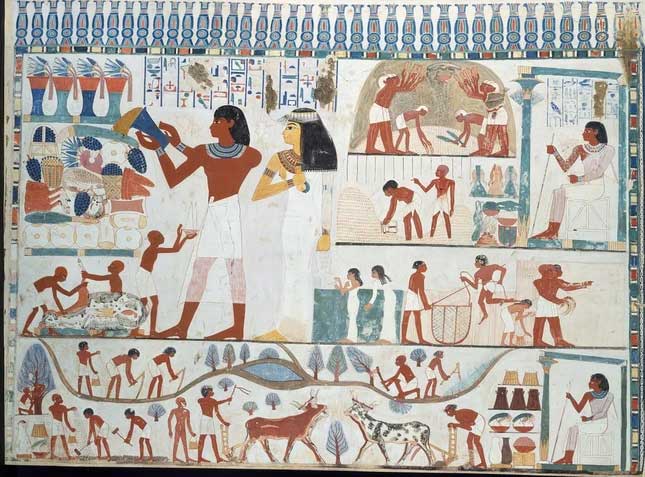

A replica of a drawing about agriculture found in the tomb of Nakht, a scribe and astronomer who lived during the reign of Pharaoh Thutmose IV. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

The ancient Mesopotamia region also learned from Egypt early on. The tax system has existed for millennia and remains “sturdy” even after the fall of ancient Egypt in the 1st century BC and up to today.

Although the tax system of ancient Egypt evolved and diversified throughout the civilization’s existence, the basic concept remained unchanged: the state taxes to fund its operations and maintain social order.

Egyptologist Toby Wilkinson at the University of Cambridge (UK) assesses that the legacy of the ancient Egyptian government and its diverse tax system, from income tax to customs duties, is clearly visible in modern versions.

Mr. Wilkinson explains: “The fundamental framework of human society has not changed in the last 5,000 years. You can recognize many management techniques invented in ancient Egypt that remain unchanged today.”

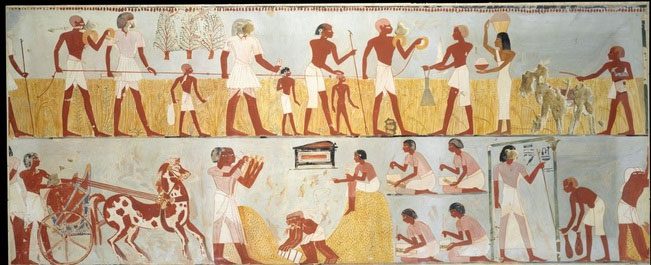

Illustration of grain threshing in ancient Egypt. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

For most of its history, ancient Egypt taxed goods. Tax officials collected taxes in the form of grains, textiles, labor, livestock, and other commodities. The amount of tax owed was often related to agriculture, with a certain percentage of harvested crops required to be delivered to granaries or administrative storage centers operated by the dynasty.

Interestingly, taxes were adjusted according to harvest yields, similar to modern income tax brackets, with different categories established based on the amount of wealth generated. Juan Carlos Moreno Garcia at the French National Centre for Scientific Research analyzes that, generally, fields with more successful harvests were taxed at higher rates.

He adds: “Fields were taxed in various ways and depended on productivity as well as the fertility and quality of the land. But the dynasty set a basic tax rate based on the height of the Nile River.”

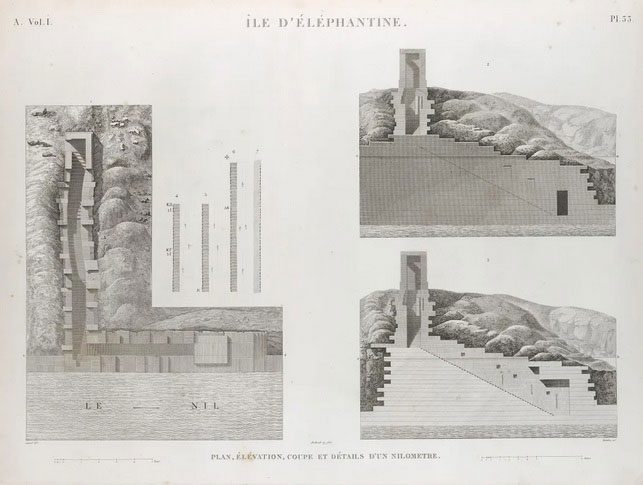

On Elephantine, an island in Upper Egypt, 19th-century archaeologists discovered a nilometer – a structure used to measure the water level of the Nile River. If the water rose above a marked line, it indicated flooding fields and poor harvests; if it fell too low, it signified drought and crop failure.

Mr. Wilkinson argues: “Egypt was fundamentally an agricultural economy and entirely dependent on the Nile River. We have records of the Nile’s height from the First Dynasty, so we believe this established the foundation for early taxation.”

A diagram of the nilometer on Elephantine. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Harvest taxes provided an important revenue source for the royal treasury. However, the Egyptian dynasty needed not only grains but also labor. This was provided through a corvée system, where the dynasty could compel all Egyptians below the rank of official to work on public projects, taking on tasks such as plowing fields, mining, and building temples and tombs.

In addition to determining tax rates and types, the ancient Egyptians also developed many methods of tax collection. During the Old Kingdom (from 2649 to 2130 BC), Egyptian pharaohs collectively taxed communities, ordering landowners to hand over products harvested by their servants. During this period, Egyptians pioneered the concept of a centralized government headed by the pharaoh, with smaller provinces known as nomes managed by local authorities.

To ensure that the nomarchs (governors) accurately reported local assets, the pharaohs of the Old Kingdom often conducted annual or biannual tours. These tours allowed the monarch to collect taxes directly rather than relying on third-party tax collectors or depending on the honesty of local governance.

By the time of the Middle Kingdom (2030 to 1650 BC), pharaohs began taxing individuals at a personal level. The annual tours of the pharaoh were no longer necessary; instead, there were scribes who meticulously kept records of tax debts and who still owed payments. This shift in tax collection strategy was achieved due to a surge in literacy rates among the population.

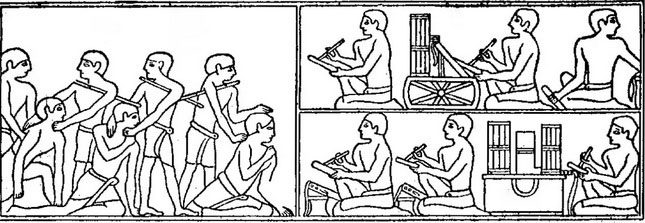

Illustration of officials arresting farmers for forced labor due to non-payment of taxes. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Most evidence of the ancient Egyptian tax system comes from the peak period of record-keeping – the New Kingdom (1550 to 1070 BC). During this time, there was always a strong force of tax collectors and scribes ensuring the Royal Treasury was well-stocked. Many pharaohs of the New Kingdom used tax money to build grand monuments and hold spectacular celebrations.

Notably, ancient Egyptians not only invented a tax management framework but also its pitfalls, which include the concepts of fraud, tax evasion, and corruption.

Scribes and nomarchs often colluded to report fewer figures to the dynasty and kept the surplus for themselves, or taxed farmers at higher rates than they were supposed to pay.

Meanwhile, taxpayers found ways to evade contributions, such as manipulating the weights of grains. Mr. Wilkinson states: “People would secretly add stones to their grains to meet the taxed weight of their fields. The problem became so severe that the royal family issued decrees prohibiting people from committing fraud.”

A depiction of harvesting in an ancient tomb. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

Around the beginning of the 13th century BC, Pharaoh Horemheb of the 18th Dynasty issued a decree stating that both tax extortion and evasion could be punished by amputation and exile. This declaration reaffirmed the public’s obligation to pay taxes to the pharaoh, as everything in the land was considered belonging to the pharaoh.

Although the social reality of ancient Egypt revolved around a strong belief in the pharaoh, who was viewed as the intermediary between humanity and the divine, common people at that time even openly protested against taxation. Some complaints centered on unfair tax appraisals.

The Egyptians’ dissatisfaction with the tax system increased after being occupied by other nations, combined with the introduction of strong foreign currency in the mid-first millennium BC. As Persians and later Macedonians occupied Egypt, they issued coinage and taxed the local population.

The Egyptians complained about paying taxes to the occupiers and also lamented the corruption of officials who embezzled funds. During the reign of King Ptolemy V around 204 BC, the Egyptians revolted against the Macedonian occupiers. To appease the Egyptian people, the Ptolemaic king sought to change tax levels for certain influential groups, such as high priests at major temples.