Before 1639, the astronomical community believed that Venus was behind and much larger than the Sun.

With skepticism and an infinite passion for astronomy, amateur researcher Jeremiah Horrocks (1618 – 1641) crafted his own telescope and personally observed the “black drop phenomenon.”

He reversed contemporary understanding, ushering in a new era of exploration that influenced many, including Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727).

A Teenager Passionate About Astronomy

Jeremiah Horrocks (1618 – 1641) was passionate about astronomy from his teenage years. (Image: Wikipedia.org).

Jeremiah Horrocks was born in 1618 in Lancashire, into a Puritan family that valued education. As a child, he often lingered in his grandfather’s clock-making workshop, a watchmaker, becoming familiar with astronomy since timekeeping was then based on sunlight.

The Puritans discussed astrology, witchcraft, and magic extensively. Horrocks doubted the credibility of astronomical claims and sought personal verification. In 1632, at just 14 years old, he walked alone from Lancashire to Cambridge, determined to enroll at the University of Cambridge to study the stars. That same year, Horrocks was admitted to Emmanuel College at Cambridge as a tuition-free student.

At school, Horrocks was greatly favored by two renowned lecturers, mathematician John Wallis and theologian John Worthington, who allowed him to study alongside them. During this time, the heliocentric theory (considering the Sun as the center of the universe) was just taking shape and causing significant debate in the academic community. Despite his youth, Horrocks was one of its supporters. He spent his days engrossed in the works of pioneering heliocentrists Johannes Kepler and Tycho Brahe.

In 1635, Horrocks abruptly left Cambridge without graduating. Some believed he was too impoverished to continue, while others speculated he had learned all that Cambridge had to offer and did not wish to waste any more time there.

The Most Shocking Discovery

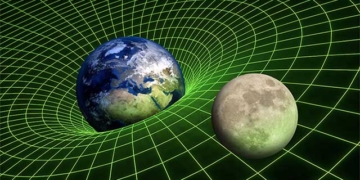

“The black drop effect” demonstrated that Venus was situated between Earth and the Sun and was significantly smaller than the Sun. (Image: Wikipedia.org)

After leaving Cambridge, Horrocks continued to seek out and read astronomical research. In 1638, at the age of 20, he personally crafted the best telescope of his time, allowing him to observe the Moon’s orbit and becoming the first to prove “the Moon moves in an elliptical orbit around the Earth.”

One of the astronomers Horrocks admired most was Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630, Germany). In 1627, Kepler published the Rudolphine Tables, predicting the transits of Mercury and Venus. According to his calculations, Mercury would transit the Sun in 1631, while Venus would do so in 1761.

According to Kepler’s Rudolphine Tables, in 1639, Venus was poised to transit the Sun. Starting in 1635, Horrocks had been studying the Rudolphine Tables and marked his doubts about this prediction. After three years of observing Venus, he made a completely different forecast: on November 24, 1639, around 3 PM, Venus would pass in front of the Sun.

On November 24, 1639, the weather was quite overcast and cloudy. At that time, Horrocks was in Many Hoole. Around 3:15 PM, he saw a small black dot appear on the Sun and knew his prediction was correct. Simultaneously, in Manchester, astronomer William Crabtree (1610 – 1644) also observed this “black drop effect.”

Crabtree was a close friend of Horrocks. Thanks to Horrocks’s prior notification, Crabtree was able to witness Venus transit the Sun firsthand. At that time, astronomers had only one way to measure the distance between the Sun and the Earth: by observing a planet positioned between the two, creating a triangle.

Before Horrocks, astronomers believed that the Sun was situated between Venus and Earth, and that it was smaller than Venus. By observing Venus transit the Sun, Horrocks successfully proved the opposite. Venus was indeed the planet situated in between; it was not only closer to Earth than the Sun, but also infinitely smaller than the Sun.

In addition to accurately predicting the date and time of Venus’s transit across the Sun, Horrocks also correctly anticipated that it would transit again on June 8 of the same year. Thanks to him, the astronomical community in England witnessed the “black drop effect.”

Early Death

The 17th century was a tumultuous time for astronomical research. During this period, religious fanaticism was not only at its peak but also extremely dominant. The church rejected scientific inquiry, dismissing any astronomical discoveries that contradicted the Bible. Even Galileo Galilei (1564 – 1642, Italy) had to bow before the court and repent for daring to claim that “the Earth revolves around the Sun.”

Horrocks’s discovery, similar to Galileo’s, disrupted religious beliefs. It served as the first work to prove that Earth was not the center of the universe as the geocentric theory suggested (considering Earth as the center of the universe with all planets revolving around it), but merely a planet within the Solar System, revolving around the Sun.

Throughout his pursuit of astronomy, Horrocks diligently recorded his observations and research methods. For reasons unknown, in 1640, he left his parents’ home in Toxteth and moved 18 miles away to Hoole. Also for unknown reasons, on January 3, 1641, at the age of 23, Horrocks passed away suddenly.

After Horrocks’s death, his parents’ home in Toxteth was searched by royalist forces. Fortunately, his close friend Crabtree had collected all of Horrocks’s letters and astronomical observations and hidden them away, later compiling them into a published book.

Two years after Horrocks’s death, Isaac Newton (1643 – 1727) was born. From his teenage years, Newton showed a keen interest in astronomy and read all of Galileo’s and Kepler’s works.

By chance, Newton discovered materials about “the error in Kepler’s Rudolphine Tables” that Horrocks had pointed out. Immediately, Newton searched everywhere for Horrocks’s materials and felt as if he had been “enlightened.”

According to scientists’ conjectures, the reason Horrocks was forgotten may likely be due to his early death. Had he lived longer and personally published his astronomical discoveries, Horrocks might have achieved fame comparable to that of Galileo.