Known as the “Crystal Eye” of the Inuit, the Pingualuit Crater was once a destination for explorers searching for diamonds. However, the true treasure of this place lies in the stories that its deep waters can tell.

This is the far northern region of Quebec, in an area known as Nunavik. Back in 1950, this area was featured in newspapers worldwide and was considered the eighth wonder of the world. Not because of its barren landscape or any man-made structures, but due to its unique geological features.

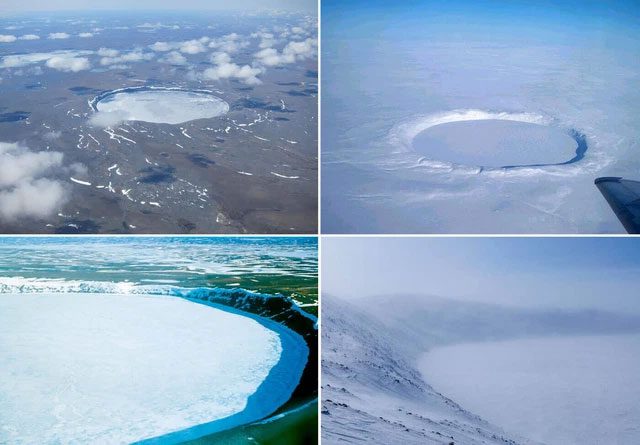

Pingualuit Crater in Nunavik, Quebec, one of the youngest and best-preserved craters on the planet. With a diameter of nearly 3.5 km and a circumference of over 10 km, this crater is not only remarkable in size but also impressively shaped like a nearly perfect circle. Markusie Qisiiq, director and guide of Pingualuit Park, stated, “The Inuit knew about the existence of this crater long before Westerners came to search for diamonds. They call this place the Crystal Eye of Nunavik.”

The Pingualuit Crater, located in Canada, nestled within the tundra of the Ungava Peninsula in northern Quebec, is known for its perfectly round crater formed by the impact of a meteorite that occurred over a million years ago. In addition to being one of the deepest lakes in North America, it is also considered the clearest and purest lake in the world, with visibility exceeding 35 meters.

On June 20, 1943, a U.S. Air Force plane on a meteorological flight over the Ungava region of Quebec captured a photo showing the wide crater rim rising above the landscape. In 1948, the Royal Canadian Air Force mapped the remote area as part of Canada’s photomapping program, although these images were not widely published until 1950.

This vast basin was first identified by the crew of a U.S. Air Force plane in June 1943, but its images were only made public in 1950. Prior to that, the crater was known only to the local Inuit, who named it the “Crystal Eye of Nunavik” or simply “Crystal Eye”.

According to studies, scientists believe that a meteorite approximately 120 meters in diameter fell through the atmosphere, traveling at speeds over 30 km/second, striking the Earth in the past, causing rocks to be ejected in all directions and creating a hole in the planet. Over time, rain and melting ice filled this hole with water. As a result, about 1.4 million years later, when we fly over the Nunavik region of Quebec, looking out the window reveals an endless tundra. We will see a blue eye with a nearly perfect circular shape, which is the Pingualuit Crater. When viewed in the light from above, it looks like a sparkling and mysterious crystal eye.

However, shortly after the modern world became aware of its existence, the crater underwent several name changes. Initially, it was called “Chubb Crater” by a diamond hunter and the first person to organize an exploratory mission here – Frederick W. Chubb. Chubb hoped that the crater was that of an extinct volcano, in which case the area could contain diamond deposits similar to those in South Africa. Thus, he and geologist V. Ben Meen from the Royal Ontario Museum took a short flight to the crater with Chubb in 1950; it was during this trip that Meen proposed the name “Chubb Crater” and “Museum Lake” for the unusual water body located about 3.2 km north of the crater (now known as Lake Laflamme).

After returning, Meen organized a proper expedition in collaboration with the National Geographic Society and the Royal Ontario Museum. They reached the site on a PBY Catalina flying boat in July 1951, landing on the nearby Museum Lake. The search for nickel-iron fragments from the meteorite was conducted using a mine detector borrowed from the U.S. Army. However, this search was unsuccessful due to the granite in the area containing high levels of magnetite.

Nevertheless, a subsequent survey found magnetic anomalies beneath the northern rim of the crater, indicating that a large mass of metallic material had been buried below the surface. The Quebec Geographic Board subsequently led a second expedition to the crater in 1954. That same year, its name was changed to “Cratère du Nouveau-Quebec” – “New Quebec Crater” at the request of the Quebec Geographic Board. It wasn’t until 1999 that it was renamed “Pingualuit”, which can be translated as “where the Earth rises.” The crater and its surrounding area are now part of Pingualuit National Park.

The crater rises 160 m above the surrounding tundra and is 400 m deep. Lake Pingualuk is 267 m deep, filling the depression and is one of the deepest lakes in North America. The lake also contains some of the purest freshwater in the world, with a salinity of less than 3 ppm (for comparison, the salinity of the Great Lakes is 500 ppm). It is one of the clearest lakes in the world, with no groundwater or connecting channels to surrounding waters, meaning the water here accumulates only from rain and snow and is lost only through evaporation.

Professor Reinhard Pienitz from Laval University led an expedition in 2007 to this crater and extracted sediment cores from the lake’s bottom, which were filled with fossilized pollen as well as algae and fossilized insect larvae. It is hoped that these findings will provide information about climate changes from the last interglacial period 120,000 years ago. Preliminary results indicate that the 8.5 m sediment core above contains records of two interglacial periods.