By the end of this decade, as it is set to be decommissioned, the International Space Station (ISS) will be guided into the atmosphere by a spacecraft and will ignite.

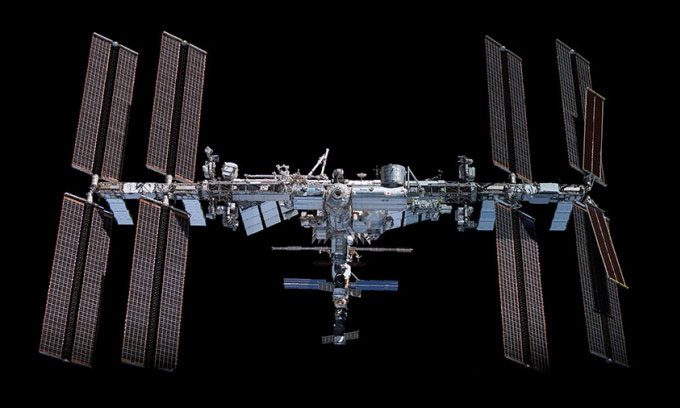

International Space Station (ISS) taken from SpaceX’s Crew Dragon. (Photo: NASA).

Currently, NASA and most international partners plan to operate the ISS until 2030. By this time, the station’s basic structure will become “exhausted” and unable to safely accommodate astronauts. Therefore, experts must find the most appropriate way to manage this massive structure, which weighs about 420 tons, as reported by New Atlas on September 24.

Five space agencies, including the Canadian Space Agency (CSA), the European Space Agency (ESA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), and Russia’s Roscosmos, have been operating the ISS since 1998, with each agency responsible for managing and controlling the hardware it provided. The station is designed for interdependent parts and operates based on contributions from its partners. The U.S., Japan, Canada, and ESA are committed to operating the station until 2030, while Russia is expected to participate in its operation at least until 2028.

When the ISS is decommissioned, pushing the station to a higher orbit will not be feasible as it would require massive amounts of energy, and the pressure on the station could cause it to break apart. The alternative solution is to bring the station down into the atmosphere in a controlled manner, allowing it to ignite, with any remaining debris falling into an uninhabited ocean area.

Initially, experts planned to use a group of Russian Progress cargo ships to push the ISS into the desired orbit. However, after thorough research, NASA and the ISS operational partners found this method to be insufficiently effective. Additionally, Russia’s planned withdrawal from the station in 2028 and the declining relationship with other partners rendered the previous plan uncertain.

As a replacement, NASA proposed that American companies develop a U.S. Suborbital Deorbit Vehicle (USDV), which would be used for the final deorbit phase after the ISS naturally descends. The vehicle could be a modification of an existing model or a completely new design. The USDV must be operational on its first flight, equipped with backup capabilities and the ability to recover from unusual incidents to continue the critical deorbiting process, bringing the ISS down into the atmosphere and igniting it. The USDV will require several years for development, testing, and certification.