1. Youth and Education

Copernicus was born in Torun, Poland, into a family of merchants and officials. His uncle, Bishop Lukas Watzelrode, took great care in ensuring that his education was solid at the finest universities.

Nicolas entered the University of Krakow in 1491, studying liberal arts for four years but did not obtain any degree. He then traveled to Italy to study medicine and law, as was common for Polish individuals at the time. Before leaving, his uncle appointed him as a canon at Frauenburg, now known as Frombork, a position responsible for financial matters without religious duties.

In January 1497, Copernicus began studying canon law at the University of Bologna and was tutored by a mathematics professor, Domenico Maria Novara (1454-1504). The professor was one of the first to accurately adjust Ptolemy’s geography and greatly encouraged him in the fields of geography and astronomy. Both observed a lunar eclipse and the star Aldebaran on March 9, 1497, in Bologna.

In January 1497, Copernicus began studying canon law at the University of Bologna and was tutored by a mathematics professor, Domenico Maria Novara (1454-1504). The professor was one of the first to accurately adjust Ptolemy’s geography and greatly encouraged him in the fields of geography and astronomy. Both observed a lunar eclipse and the star Aldebaran on March 9, 1497, in Bologna.

In 1500, Copernicus organized an astronomical conference in Rome.

The following year, he was allowed to study medicine at Padua (the university where Galileo would study nearly a century later).

In 1503, he earned a doctorate in law and returned to Poland to complete his administrative duties (without finishing his medical studies).

2. Works

From 1503 to 1510, Copernicus lived in his uncle’s bishopric castle in Lidzbark Warminski, participating in the administration of the diocese.

He published his first book, a translation from Latin of a moral treatise by a 7th-century Byzantine author, Theophylactus de Simocatta.

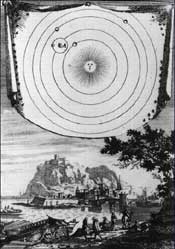

From 1507 to 1515, he completed his work on astronomy: De Hypothesibus Motuum Coelestium a se Constitutis Commentariolus, known as the Commentariolus, which was not published until the 19th century. In this work, he presented the principles of his new astronomical theory: the heliocentric theory with the Sun at the center.

After returning to Frauenburg in 1512, he participated in the work of reforming the calendar (1515).

1517: He wrote a treatise on currency and began his major work: De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres). He completed this work in 1530, but it was not published until 1543 in Nuremberg. Copernicus received a few copies just hours before his death (May 24, 1543). He sent one copy to Pope Paul III, presenting his system as a purely theoretical framework to avoid the Church’s condemnation.

3. The Copernican System and Its Influence

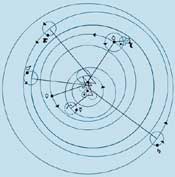

The Copernican system is based on the assertion that the Earth rotates on its axis once every day and revolves around the Sun once a year.

The Copernican system is based on the assertion that the Earth rotates on its axis once every day and revolves around the Sun once a year.

Additionally, other planets also orbit around the Sun. Thus, the Earth experiences precession on its axis as it rotates (much like a top that spins while also revolving).

The Copernican system retained some ancient theories, such as solid spheres carrying the planets and making the stars stationary.

Copernicus’s theory had advantages over Ptolemy’s by explaining the daily motion of the Sun and stars (due to the Earth’s rotation) and the annual motion of the Sun (due to the Earth’s revolution around the Sun). He explained the apparent retrograde motion of Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Mercury, and Venus maintaining their distance from the Sun.

Moreover, the Copernican theory provided a new order of planets based on their orbital periods.

One significant difference between the Copernican and Ptolemaic systems is that the larger the orbital radius of a planet, the longer it takes for that planet to complete one orbit around the Sun.

However, the concept of a moving Earth was difficult for 16th-century readers to accept in understanding Copernicus’s theory. Some of his ideas were accepted, but the idea of the “Sun-centered” model was rejected or unknown.

However, the concept of a moving Earth was difficult for 16th-century readers to accept in understanding Copernicus’s theory. Some of his ideas were accepted, but the idea of the “Sun-centered” model was rejected or unknown.

From 1543 to 1600, he had only ten followers. Most of them worked outside the university, in royal courts. The most notable among them were Galileo and Johannes Kepler. These individuals had unique arguments supporting the Copernican system.

In 1588, the Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe studied a unique intermediate position where the Earth appeared to be stationary while all other planets revolved around it.

In 1633, despite Galileo being tried by the Roman courts, several philosophers of the time still accepted (internally) the Copernican theory.

By the late 17th century, as celestial mechanics advanced thanks to Isaac Newton, most scholars in England, France, the Netherlands, and Denmark accepted Copernicus’s ideas, while other countries resisted Copernican theory for nearly a century.

————————————-

Stay tuned for more: “Nicolas Copernicus – Questions from the Vineyard”

Continue reading: “Nicolas Copernicus – The Destruction of a Great Work”