The ancient and mysterious writing system of the Elamite people, from the region that is now southern Iran, was used approximately from 2300 BC to 1800 BC.

Finally, science has managed to decode it, although some experts remain skeptical about these results.

Only about 40 artifacts containing Elamite writing still exist today, making the task of deciphering this writing system extremely challenging. However, researchers report that they have completed much of this work and published their findings in the journal Ancient Near Eastern and East Asian Script Studies archaeology.

The key to the researchers’ success was the analysis of eight inscriptions carved on silver cups.

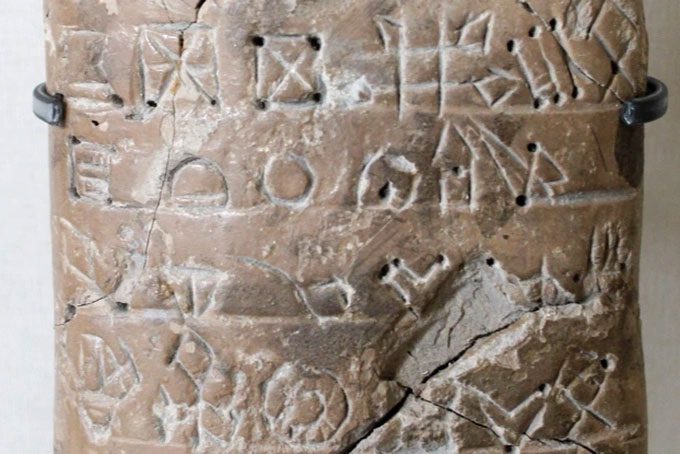

Inscription on an Elamite engraved tablet.

Previously, another research group had decoded other Elamite inscriptions, and this time the scientists relied on those findings to compare with the writing system in the eight Elamite cuneiform inscriptions (a form of writing that has been deciphered and was used in what is now the Middle East) from the same period, which recorded the names and titles of the same lords, as well as many similar phrases describing these lords. From this, they inferred the meanings of other symbols.

However, approximately 3.7% of the Elamite characters remain undeciphered.

The research team translated a passage stating: “Puzur-Sušinak, king of Awan, is favored by the god Insušinak.” The passage also stated that anyone who revolts against Puzur-Sušinak would be destroyed. They indicated that they would publish further translations of other passages at an appropriate time in the future.

Some experts not involved in this research declined to comment on the results. However, Jacob Dahl, a professor of ancient Near Eastern scripts at the University of Oxford, expressed uncertainty about whether the research team had successfully deciphered the writing.

Professor Dahl studies a different script called primitive Elamite, and he disagrees with the research team’s claim in their article that primitive Elamite and linear Elamite are closely related.

Moreover, he is also unsure whether the team used texts found at the Bronze Age archaeological site of Konar Sandal (in Iran), as these texts have dubious characteristics and may be forgeries.

He emphasized that the artifacts at Konar Sandal are not among the eight newly discovered inscriptions that the research team focused on, but all studies questioning the deciphering of Elamite writing have used artifacts from Konar Sandal.

Where do these inscriptions come from?

Experts are uncertain about the origins of these eight Elamite inscriptions. Seven of them are in the collection of collector Houshang Mahboubian, while the eighth belongs to Norwegian businessman Martin Schøyen. Mr. Schøyen is also an antiquities collector, with a team dedicated to searching for artifacts across continents and frequently collaborates with scholars.

The eighth inscription, along with hundreds of other artifacts in his collection, was temporarily seized by Norwegian police on August 24, 2021. A report from the Oslo Museum of Cultural History, published in March 2022, stated that Mr. Schøyen could not provide documentation proving the legal export of this artifact from Iran nor transparent financial records regarding the costs of acquiring it. This suggests that the artifact may have been smuggled.

In July 2022, Mr. Schøyen denied the aforementioned report, claiming that at least one of the report’s authors harbored bias against him and that the report’s assertion labeling his collected items as smuggled was “completely unfounded.” He asserted that his Elamite inscription originated from the ancient city of Susa in Iran.

His lawyer stated: “In 40 years of practicing law, I have read countless reports. I have never seen a report so poorly constructed that it was surprising.”

Researchers also noted that the origins of the seven inscriptions in Mr. Mahboubian’s collection have not been fully clarified.

François Desset, one of the study’s authors and an archaeologist at the University of Tehran and a member of the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS), stated that Mr. Mahboubian claims the artifacts were found during excavations conducted by his father in 1922 and 1924 in the two cities of Kam-Firouz and Beyza in Iran and were brought to Europe before 1970.

According to another study in 2018 from Iran published in the Journal of the Institute for Persian Studies in the UK, metallurgical and chemical analyses of Mr. Mahboubian’s artifacts found no evidence of forgery. The layer of rust indicates that these objects had been buried for a long time, proving their authenticity.

Additionally, the production process and the silver content in these objects also affirm their authenticity. Technical reports indicate they are ancient artifacts, not sophisticated forgeries.

In the 1980s, Mr. Mahboubian and part of his collection became the focus of media attention. In 1987, he was convicted of hiring a thief to steal some antiques from his own collection for insurance money. This conviction was overturned in 1989, and previous allegations became subjects of investigation. The appeals trial did not take place, and all charges and penalties were dropped.

When asked about the research results mentioned above, representatives of Mr. Mahboubian did not comment.