In the mid-16th century, the scientific revolution began with the astonishing discovery by Nicolaus Copernicus that the Earth and other planets orbit the Sun in perfect circular paths. Johannes Kepler believed that Copernicus was mistaken about the shape of these orbits and argued that they were not perfect circles.

Kepler had access to relatively accurate measurements of Mars’ movements in the sky, conducted by his mentor, astronomer Tycho Brahe. Using these measurements, Kepler manually calculated the orbit of Mars, but his calculations were endless, and he consistently made errors without being able to find the correct answer.

After four years, Kepler finally completed his lengthy 900-page calculation—and he had to repeat it 70 times. Fortunately, Kepler was unaware that there were still errors in these calculations, but remarkably, these errors canceled each other out, making the calculations still valid.

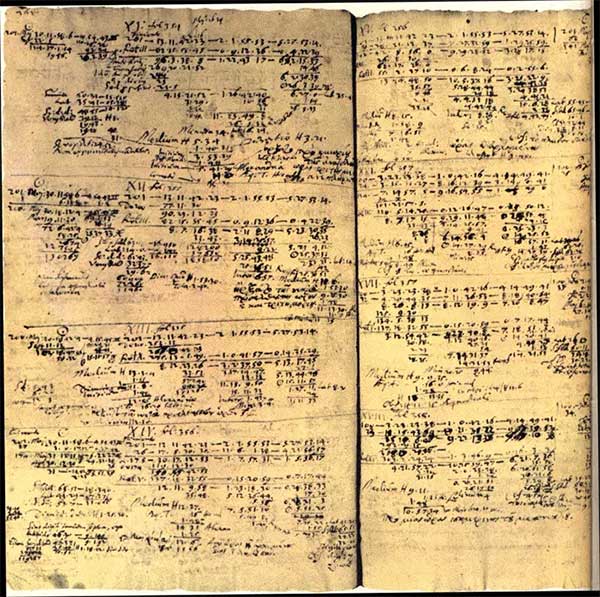

One of Kepler’s 900 pages detailing calculations of Mars’ motion. During that time, the decimal point had not yet been invented, so Kepler continuously had to write fractions in his documents.

Kepler’s case is not unique. Throughout history, difficulties in performing complex calculations have caused many troubles for scholars and hindered the development of human knowledge. These challenges paved the way for the invention of a revolutionary calculating tool in human history: the slide rule.

The Birth of the Slide Rule

As the scientific revolution progressed, calculations became increasingly difficult to perform. Researchers and engineers required precise scientific measurements, and with the development of mathematics, scientists needed to carry out longer and more complex calculations. Then, a miracle happened.

Scottish mathematician and astronomer John Napier discovered a function he called “logarithm”, which allowed complex multiplication and division to be transformed into simple addition and subtraction.

Portrait of John Napier

For instance, if (10^3) equals 1,000, then the logarithm base 10 of 1,000 is 3, or Log(1000) = 3. Similarly, Log(100) = 2. Adding these together gives 5, which corresponds to the fifth power of 10 = 100,000. More generally, this calculation can be expressed as adding two real numbers: Log(ab) = Log(a) + Log(b).

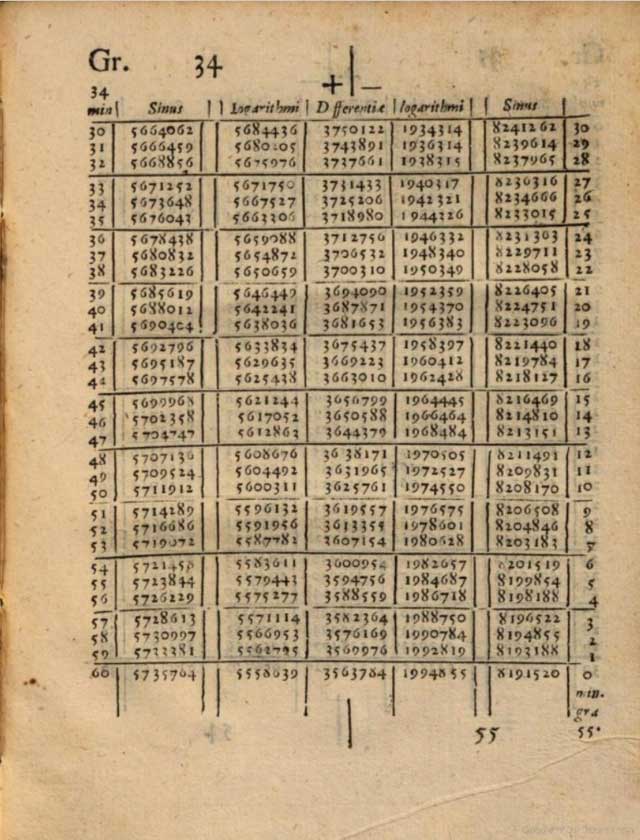

In 1614, after nearly 20 years of hard work, Napier published his discovery in a 90-page table—an index listing logarithms of about 10 million numbers. It allowed users to find the product of two numbers by looking up the logarithm of each number in the table, adding the two logarithms together, and finding the number whose logarithm matched this result, thus obtaining the product.

For example, when astronomers needed to multiply two trigonometric values: 0.57357 and 0.42261, using the logarithm table, they could find the two closest logarithmic values to be -0.24141 and -0.37406. Adding these logarithmic numbers together gives -0.61547, and the corresponding number in the table for this logarithm is 0.242399. This number is approximately equal to the result of the aforementioned multiplication.

A page from John Napier’s logarithm book. The leftmost column lists angles from 30 to 60 degrees (to the right are angles from 0 to 30 degrees), beside it is the sine of those angles, followed by the natural logarithm of that sine. The middle column shows the difference between these two logarithms, or the natural logarithm of the tangent function.

At a time when calculators had not yet been invented, this was the easiest way to perform relatively accurate complex multiplication and division. However, mathematicians still had to sift through a lengthy 90-page table to find the numbers they needed, which remained a time-consuming process.

In 1620, English astronomer and mathematician Edmund Gunter developed a special slide rule that could calculate the product of two numbers by measuring lengths on the rule, rather than searching through a lengthy 90-page table. The rule was designed so that the length from its start to any number x corresponds to its logarithm.

Edmund Gunter’s logarithmic slide rule

This rule starts at number 1, with Log(1) = 0, making the distance to 1 equal to 0. The distance from 1 to 3 is half the distance from 1 to 9 because Log(3) = ½ Log(9). To calculate the product of any two numbers a and b, the user measures the distance from the start of the rule to that number to find its logarithm and then adds them together, subsequently comparing this distance on the rule to find the result of the calculation.

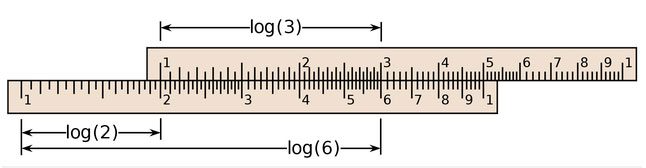

Then, by 1622, William Oughtred invented the first slide rule. It was a simple and user-friendly calculating tool, featuring two logarithmic scales that could be aligned and slid parallel to each other. To calculate the product of two numbers a and b, one simply needs to align the number 1 on the upper scale with the number a on the lower scale and then check which number on the lower scale aligns with the number b on the upper scale.

Example of using Oughtred’s slide rule. To perform the calculation (2 times 3), align number 1 on the upper scale with number 2 on the lower scale, and the number on the lower scale aligned with number 3 on the upper scale is the result of the calculation: number 6.

Since the distance of Log(ab) = Log(a) + Log(b) is measured from the start of the lower scale to this number, this is indeed the result of the product calculation between a and b. Conversely, this process yields the result of dividing two numbers. For example, to divide ab by b, place number b on the upper scale aligned with ab on the lower scale, then find the number aligned with number 1 on the upper scale to obtain the result of the division.

350 Years of Service in Calculating for Humanity

This simple slide rule sparked a revolution in performing multiplication and division calculations. It became a popular tool among mathematicians, scientists, engineers, doctors, geographers, military personnel, pilots, tax officials, and many others. This tool appeared alongside nearly every invention, every design of historical structures, and in every scientific advancement for almost 350 years.

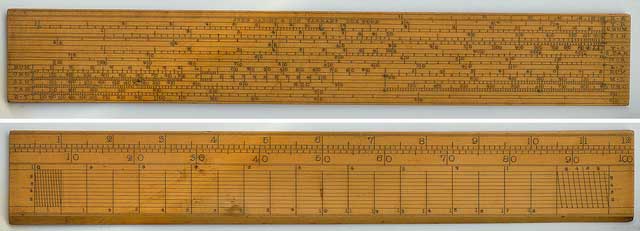

As it became more widely used, it also became increasingly complex. Alongside the “standard” logarithmic scale, the slide rule was supplemented with many other calculations, such as calculations for sine, square roots, and exponentials.

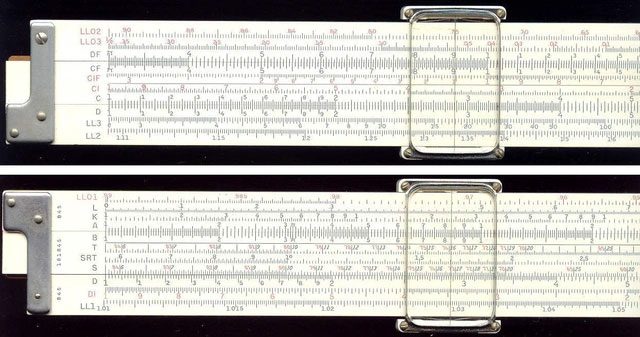

Front and back of the Keuffel & Esser 4081-3 slide rule, which, in addition to calculating many more functions, features a slider on top for easier visibility of numbers.

In addition to calculating common operations, some special types of slide rules with specific scales were designed for specific calculations. For example, they were used to convert between different units of measurement, calculate bank loans, perform engineering calculations, and even a complete flight measure used for calculations related to aviation. There were also circular and cylindrical slide rules.

A technician on a British bomber is using a slide rule to calculate the aircraft’s fuel consumption, October 1941.

Although regarded as an advanced tool for centuries and even used in the invention of numerous other mechanical calculating tools, the rapid development of digital computers with their superior computational abilities has made these slide rules increasingly difficult to find a place in modern use.

In fact, as early as 1972, an article lamented the death blow from electronic computers that led to the near disappearance of slide rules: “When an engineer or scientist needs a quick answer to a problem involving many multiplications, divisions, or complex functions, he often turns to his slide rule. However, before long, that loyal stick will have to retire. Now, a pocket electronic calculator can provide answers more easily, quickly, and accurately.“

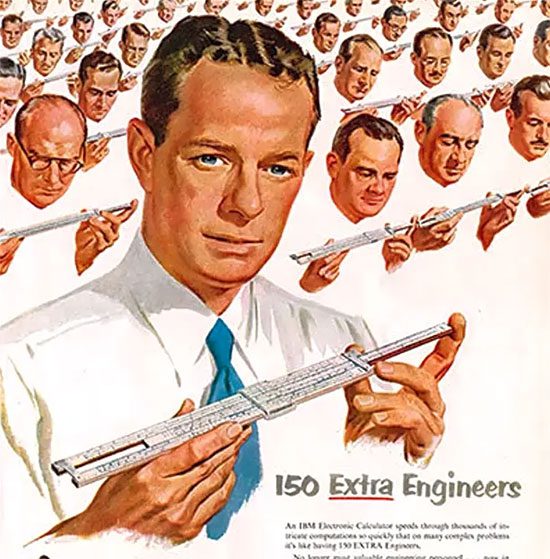

Image marking the end of the slide rule era: An IBM computer advertisement from 1951 promoting that each computer could replace 150 engineers using slide rules.

The emergence of electronic computers, followed by digital computers, marked the end of a significant chapter in the history of science and humanity – a period lasting over 300 years that relied on a simple calculating tool for groundbreaking discoveries that changed the course of world history.