When it comes to mummies, people immediately think of the pyramids and the embalming techniques of the Egyptians.

However, several other cultures around the world also have methods that help preserve bodies for centuries. Notably, Japan has a mysterious technique of self-mummification.

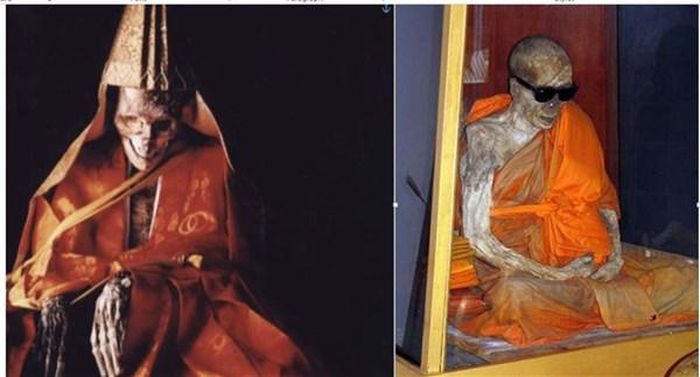

Mummies of monks that have lasted for centuries.

Originating from Beliefs

Although Japan’s climate is not entirely conducive to mummification, somehow, some monks of the Shingon sect discovered a way to self-mummify through rigorous training. Between 1081 and 1903, about 20 monks in Japan self-mummified while still alive. This process is known as Sokushinbutsu, meaning “to become a Buddha in the body of a monk.”

Many cultures have practiced mummification, not just Egypt and Japan. The question arises: why do people want to preserve their bodies after death? The answer is found in the beliefs of many religions around the world. An immortal corpse is seen as a symbol of divine power.

In Egypt, royal mummification represents the power of rulers. Many believe that mummification is an important ritual to help the deceased’s soul pass through the afterlife. The discovery of jars containing essential items such as food, clothing, and even jewelry in Egyptian tombs alongside mummies is evidence of this.

However, this is very different from the mummification practices in Japan. Here, the monks self-mummify while still alive, with boundless will and courage.

A Long and Grueling Process

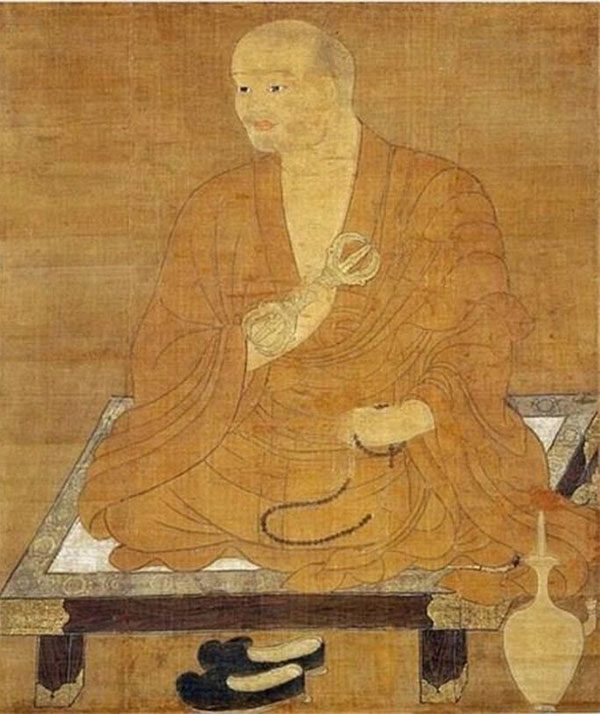

Master Kukai, founder of the Shingon sect.

The practice of Sokushinbutsu was initiated by Kukai, a monk who lived in the 9th century and founded the Shingon Buddhism sect in 806 AD.

According to a document about Kukai that appeared in the 11th century, he did not die at the time of his passing (in 835 AD) but entered his tomb, meditated deeply, and chanted. Legend has it that Kukai will reappear in 5.67 million years and guide some souls toward salvation.

Monks practicing the living mummification ritual see this as a sacrifice for humanity. They believe that living mummification will lead a person to the path of becoming a Buddha in the body they receive in this life.

Many believe that this ritual also allows monks to reach Tusita Heaven, living there for 1.6 million years and gaining the power to protect humanity on our planet. However, only a few succeed in this ritual after undergoing an incredibly challenging process that often lasts more than three years.

Actively embracing death, including three years of preparation to ensure the body does not decay, requires perseverance and courage from the practitioner. Monks practicing Sokushinbutsu must follow a strict diet, avoiding grains, eliminating wheat, rice, millet, and soybeans.

Instead, they will eat items such as nuts, berries, pine needles, tree bark, and tree resin (which is why the Sokushinbutsu diet is called mokujikyo, or “tree eating”).

Spiritually, this diet aims to enhance spiritual strength while helping the practitioner increasingly detach from the human world. The diet and meditation rituals of the monks will eliminate moisture, fat, and muscle. These changes in the body will resist decay even after death.

Many monks complete a thousand-day cycle with the mokujikigyo diet. However, some wish to undergo two or even three cycles before feeling fully prepared.

In the final stage of the Sokushinbutsu process, monks stay in a sealed tomb. Their only connection to the outside world is a small bamboo air tube and a bell. They ring the bell daily to let those outside know they are still alive.

If there is no sound from the bell, it means the monk has died in a meditative state, chanting the name of the Buddha, known as nenbutsu. At that time, the air tube will be removed, and the tomb will be sealed. After a thousand days, the tomb is excavated to see if the body has decayed. If the body is still intact, it means the deceased has achieved

Sokushinbutsu, will be dressed in a robe, and taken to a temple for worship. If the corpse shows signs of decay, the disciples will perform an exorcism ritual, then seal the tomb again, and the monk will rest here forever.

Many Sokushinbutsu mummies have been found in northern Japan, some of which are centuries old and are revered by many devotees.

This self-mummification practice was carried out in Japan from the 11th century until the 19th century. In 1877, Emperor Meiji decided to end this form of “self-mummification.” A new law was enacted prohibiting the opening of the tomb of someone who had practiced Sokushinbutsu. However, this ritual continued, albeit very rarely, until the 20th century.

The last monk to illegally practice Sokushinbutsu was Bukkai in 1903. In 1961, researchers at Tohoku University excavated his tomb, finding the body nearly intact. Currently, the mummy rests at Kanzeonji, a Buddhist temple built in the 7th century in southwestern Japan.

The most famous for Sokushinbutsu is Daijuku Bosatsu Shinnyokai-Shonin, a monk who self-mummified at the age of 96 in 1783. His mummy is currently housed at the Ryusui-ji Dainichibou temple in Tsuruoka City, Yamagata Prefecture. Most monks underwent the self-mummification process near this sacred temple.