|

H5N1 Virus captured by the Central Institute of Epidemiology |

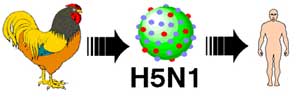

Why is it called bird flu? Because it is a virus that causes flu in birds; these viruses naturally occur in bird species. Wild birds around the world carry the virus in their digestive tracts but often do not get sick from this virus. However, the flu can spread extensively among birds and can cause domestic fowl such as chickens and ducks to become ill and die.

Typically, avian influenza viruses do not infect humans, but there have been many cases of human infection with avian influenza viruses since 1997.

How do avian influenza viruses differ from human influenza viruses? The avian influenza A virus has many subtypes; these subtypes differ due to the presence of certain proteins on the surface of the influenza A virus (hemagglutinin HA and neuraminidase NA).

Influenza A virus has up to 16 HA subtypes and 9 NA subtypes; there may also be many other combinations of HA and NA proteins, each combination creating a different subtype. All subtypes of the influenza A virus can be found in birds.

However, when discussing “avian influenza,” it refers to the subtypes of influenza A primarily found in birds. These subtypes usually do not infect humans but still have the potential to do so. When referring to “viruses that cause flu in humans,” it pertains to the subtypes that commonly occur in humans.

So far, only 3 subtypes of the virus causing influenza A in humans have been identified (H1N1, H1N2, and H3N2), and it is likely that some genes of the human influenza A virus originated from birds. The influenza A virus frequently changes and can adapt over time to infect and spread among humans.

What are the symptoms of avian influenza in humans? Symptoms may resemble typical flu symptoms (fever, cough, sore throat, and muscle aches) or eye pain, pneumonia, severe respiratory illness (such as acute respiratory distress), and many other life-threatening complications. The symptoms of avian influenza in humans depend on which virus is causing the illness.

How does avian influenza spread? Saliva, nasal secretions, and feces from infected birds/domestic fowl all contain the virus. Birds and domestic fowl become infected when they come into contact with these excretions or contaminated surfaces. It is believed that most cases of human infection with avian influenza viruses are due to contact with infected birds or contaminated ground. The transmission of avian influenza virus from infected humans to healthy individuals remains rare and has not been observed to spread beyond one person.

What is the risk of a human pandemic caused by avian influenza? The H5N1 virus typically does not infect humans. However, the first case of transmission from birds to humans occurred in 1977 during an outbreak of avian influenza in Hong Kong. The virus caused severe respiratory illness in 18 individuals, 6 of whom died. Since then, there have been no further cases of H5N1 infection in humans.

Recent cases of H5N1 infection in humans have occurred in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam coinciding with major outbreaks of avian influenza. The World Health Organization has also reported human cases in Indonesia. Most of these cases occurred among individuals in contact with infected domestic fowl or contaminated areas; however, it is believed there have been a few instances of H5N1 transmission from person to person. To date, human-to-human transmission of the H5N1 virus remains rare and has not exceeded one person, but influenza viruses have the potential to mutate. Scientists are concerned that the H5N1 virus could one day infect humans and spread easily from person to person. Because these viruses do not frequently infect humans, they do not often produce immunity for protection. Once the H5N1 virus becomes easily transmissible and spreads from person to person, a pandemic could emerge; thus, experts are closely monitoring the developments of avian influenza in Asia.

Recent cases of H5N1 infection in humans have occurred in Cambodia, Thailand, and Vietnam coinciding with major outbreaks of avian influenza. The World Health Organization has also reported human cases in Indonesia. Most of these cases occurred among individuals in contact with infected domestic fowl or contaminated areas; however, it is believed there have been a few instances of H5N1 transmission from person to person. To date, human-to-human transmission of the H5N1 virus remains rare and has not exceeded one person, but influenza viruses have the potential to mutate. Scientists are concerned that the H5N1 virus could one day infect humans and spread easily from person to person. Because these viruses do not frequently infect humans, they do not often produce immunity for protection. Once the H5N1 virus becomes easily transmissible and spreads from person to person, a pandemic could emerge; thus, experts are closely monitoring the developments of avian influenza in Asia.

How is avian flu treated in humans? The H5N1 virus currently developing in Asia has caused illness and death in humans and has shown resistance to amantadine and rimantadine, two antiviral medications commonly used to treat influenza. Two other antiviral drugs, oseltamivir and zanamivir, may be effective in treating influenza caused by H5N1, but further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of these drugs.

Tamiflu is the brand name for oseltamivir, packaged as 75 mg capsules in light blue/yellow gelatin capsules or as a white suspension with a fruity aroma, and is the most talked-about medication for avian influenza. Antiviral medications inhibit the effects of the virus in the body; they are used to treat influenza in patients who have just begun to show symptoms; they are also used for the prevention of influenza virus infection and for other purposes.

If you have kidney, liver, chronic illnesses, or other serious conditions, you should not take the medication, or if you do, the dosage must be adjusted, and special monitoring is required. Tamiflu is classified by the FDA as Category C, meaning it is unclear whether the drug is harmful during pregnancy, so it should not be taken if pregnant unless advised by a physician. It is also unclear if Tamiflu passes into breast milk and poses a risk to breastfeeding infants; therefore, it should not be used while breastfeeding. The safety and efficacy of Tamiflu have not been established in individuals under 18 years of age for treating influenza virus and in children under 13 years for the prevention of influenza virus infection.

Possible side effects of Tamiflu include allergic reactions (difficulty breathing, throat constriction, swelling of the lips, tongue, or face, or rash). Less serious side effects may still allow for continued use, but you should inform your physician if you experience the following signs and symptoms: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea; abdominal pain; headache; dizziness; fatigue; or any unusual discomfort such as insomnia, cough, or other respiratory symptoms.

Concerns that Tamiflu may not be strong enough to combat an H5N1 pandemic continue to be raised. Strains of the virus resistant to Tamiflu may still be sensitive to other antiviral medications such as Relenza (zanamivir). Therefore, it is crucial to stockpile both Tamiflu and Relenza in preparation for a potential pandemic. Since viruses can mutate, excessive use of Tamiflu should be avoided; some individuals treated have produced mutated strains of the virus. These mutated viruses seem to be less transmissible than wild-type strains, raising hopes that these viruses will not spread easily. While the mutated strains are sensitive to Relenza, there is no guarantee that Relenza will be effective against avian influenza.

Is there a vaccine to protect humans against H5N1 infection? Currently, there is no vaccine that can protect humans against the H5N1 virus. However, efforts to create a vaccine are just beginning. Vaccine trials commenced in April 2005 and are still ongoing.

Dr. ĐÀO XUÂN DŨNG