Archaeologists have gained a deeper understanding of why tooth extraction rituals were practiced in ancient Taiwan and other parts of Asia, often for very… unusual reasons.

While tooth extraction has been documented worldwide, it is frequently associated with the Austronesian communities, including those in Taiwan, Southeast Asia, and Polynesia.

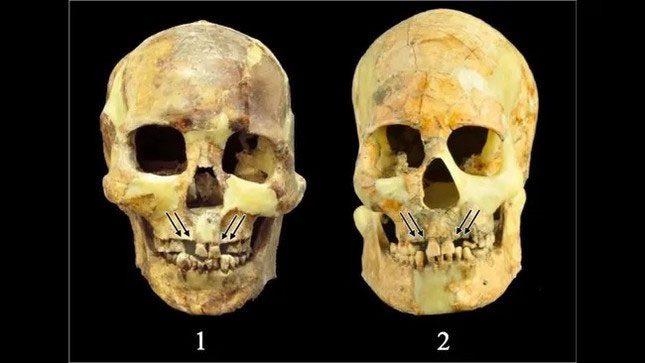

Example of tooth extraction on two skeletons. The arrows point to the extracted teeth. (Photo: Cheng-hwa Tsang)

According to a study published in the December 2024 issue of the Asian Archaeological Research journal, this practice was first introduced in the region around 4,800 years ago, during the Neolithic period, and continued until the early 20th century. It involved extracting healthy teeth, including incisors and canines, without anesthesia. Subsequently, the tooth sockets were filled with ash to prevent bleeding and inflammation.

After collecting data from over 250 archaeological sites across Asia, researchers found that 47 sites contained graves from the Neolithic period (4,800 to 2,400 years ago) to the Iron Age (2,400 to 400 years ago) where individuals had lost teeth. This ritual was uniformly applied to both males and females. However, by the 1900s, it became more common among the latter group. Additionally, it was not only adults who underwent tooth extraction; children did as well.

Aesthetic Expression

The primary reason people underwent this procedure was for aesthetic purposes—referred to as “aesthetic expression,” researchers indicate. They determined this based on examples provided in historical documents and more modern literature.

“The first and most cited motivation is beautification, stemming from the desire to differentiate oneself from the features of animal faces, as well as to enhance personal attractiveness, particularly to the opposite sex,” the authors wrote in the study. “An intriguing testimony emphasizes the pursuit of a deep red tongue protruding through the gap of shiny teeth.”

A Test of Courage

Researchers also suggested that tooth extraction was viewed as a “test of courage” as well as a precautionary measure.

Moreover, “Local people believed that tooth extraction could alleviate pain during tattooing or reduce difficulties in pronunciation,” the authors wrote. “In many cases, the visible results were considered evidence of bravery or a measure of maturity.”

Another reason, drawn from ethnographic records in Borneo and historical descriptions from southwestern China, might be that if a person experienced locked jaws, tooth extraction could facilitate easier feeding and medication.

“The most practical reason for saving a tooth-extracted patient can explain its persistence, despite the procedure being very painful,” the researchers noted. “Although cases of locked jaws may be quite rare, the preventive care involved in tooth extraction outweighed the prospects of mortality.”