A 200-ton asteroid plunged to Earth on a unique trajectory, creating a series of meteorite fragments scattered over a vast area.

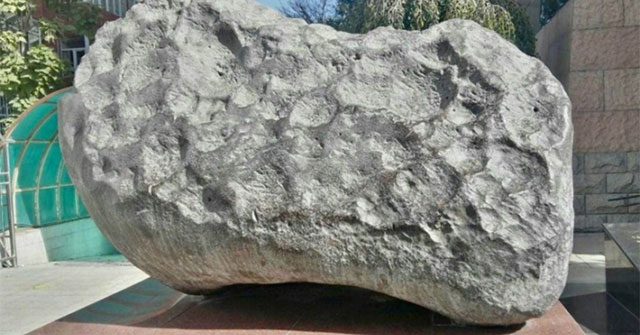

The largest Aletai meteorite weighing 28 tons discovered by a farmer in 1898. Photo: SCMP

A long time ago, the Aletai asteroid entered the atmosphere above what is now the Altai region in Xinjiang, China. The thermal shock ripped it apart into numerous pieces, resulting in one of the largest iron meteor showers ever recorded.

The fragments—some weighing 20 tons and others several dozen kilograms—are scattered over a vast area spanning approximately 430 kilometers, making it the longest meteorite field ever documented. This site is unlike any meteorite field previously observed by scientists: fragments from the same parent body typically do not lie more than 30 to 40 kilometers apart.

Using numerical modeling, an international team of scientists from China, the United States, and Europe discovered that Aletai may have entered the atmosphere at a low angle, following a trajectory similar to a stone skimming across the surface of a lake. This new finding was presented in the journal Science Advances at the end of June.

“This is the first time such a unique trajectory has been identified. This trajectory explains why the Aletai asteroid has the longest meteorite field ever recorded. A meteorite field is an elliptical area containing fragments from a single fall,” said Thomas Smith, a researcher at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who was not involved in the study.

The new research also helps explain why the meteorite fragments did not create impact craters upon striking the ground. This is because energy was dissipated during the long flight, Smith added.

The study’s results will aid scientists in better assessing the collision risks and hazards posed by asteroids based on their flight trajectories, as well as indicating potential locations for finding additional fragments from Aletai.

In the new study, the international team used various combinations of initial mass, speed, and impact angle to simulate the asteroid’s trajectory. They found that Aletai measured between 2.1 and 4.7 meters in diameter and weighed over 200 tons. It traveled at speeds of 43,200 to 54,000 km/h, entering the atmosphere at angles of 6.5 to 7.3 degrees.

“The impact angle plays a crucial role. If it were steeper or shallower, the asteroid would have created a much shorter meteorite field or bounced back into space,” explained Hsu Weibiao, a researcher at the Purple Mountain Observatory and a co-author of the study.

To date, over 74 tons of meteorite fragments from Aletai have been recovered. The largest, discovered by a farmer in a ditch in 1898, weighed up to 28 tons. Many iron meteorite fragments have been found in this area since 2004, but scientists initially did not recognize that they originated from the same asteroid. In 2015, Hsu and colleagues compared the mineral composition and trace elements in the three largest fragments. They found shared characteristics and collectively named them Aletai.

There is still much to investigate about Aletai, such as the timing of the meteor shower. “‘The terrestrial age’ of the Aletai meteorite fragments may be relatively short and difficult to quantify in the laboratory,” Smith noted. The research team also indicated that their model may change as more Aletai meteorite fragments are collected in the future.