Researchers have clarified the uneven distribution of animal species on either side of the mysterious boundary that runs through Indonesia, known as the Wallace Line.

A new study from scientists at the Australian National University reveals that a mysterious boundary emerged tens of millions of years ago after the collision of the continents of Australia and Asia, forming the Malay Archipelago and causing severe climate changes that led to the separation of animal species on each side.

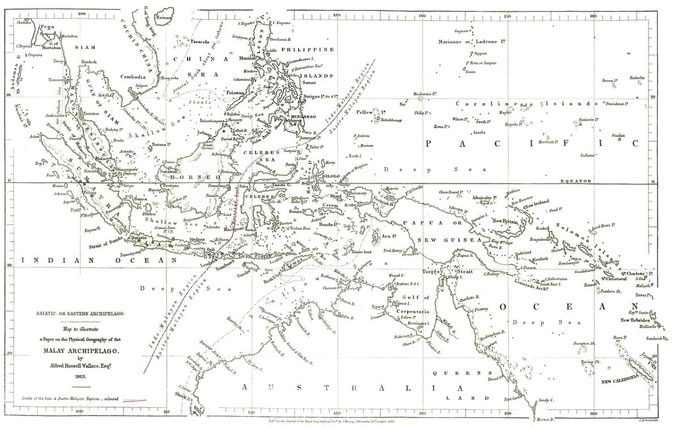

The Wallace Line, a broken red line, is likened to a biological barrier that existed tens of millions of years ago. (Photo: Live Science).

In 1863, English naturalist and explorer Alfred Russel Wallace (famous for proposing the theory of evolution by natural selection alongside Charles Darwin) observed during his travels through the Malay Archipelago that the distribution of animal species changed significantly after a certain point.

This boundary was named the Wallace Line, resembling a biogeographical barrier.

On the Asian side, species are exclusively of Asian origin. However, on the Australian side of the boundary, the animals are a mix of both Asian and Australian regions. For over a century, the asymmetrical distribution of species along the Wallace Line has puzzled ecologists.

They could not determine why Asian species could move in one direction while Australian species were prevented from moving in the opposite direction.

In recent years, a new hypothesis has emerged.

Researchers believe that the uneven distribution of animal species along the Wallace Line is due to severe climate changes resulting from tectonic activity that occurred around 35 million years ago, when Australia broke away from Antarctica and came into contact with Asia, forming the Malay Archipelago.

The researchers utilized computer models to simulate how animals were affected by climate impacts caused by continental interactions.

The model took into account dispersal abilities, ecological preferences, and evolutionary relationships of over 20,000 animal species found on either side of the Wallace Line. The results indicated that Asian species were much better suited to live in the Malay Archipelago at that time.

Climate Change

The climatic changes at that time were not caused by the movement of continents but rather stemmed from their impact on Earth’s oceans.

Map of the Malay Archipelago drawn by Alfred Russel Wallace in 1863, featuring the Wallace Line. (Photo: Alfred Wallace).

The lead author of the study, evolutionary biologist Alex Skeels from the Australian National University, stated: “As the continent of Australia drifted away from Antarctica, it opened up the deep ocean area surrounding Antarctica, where the Antarctic Circumpolar Current (ACC) flows.

This significantly altered the entire climate of the Earth, making our planet much cooler.”

The ACC, which surrounds Antarctica, is the largest ocean current in the world and plays a crucial role in regulating today’s global climate.

The model revealed that climate changes did not affect all species equally. The climate in Southeast Asia and the Malay Archipelago was much warmer and more humid compared to Australia, which was colder and drier.

“As a result, Asian organisms adapted well to life in the Malay Archipelago and used it as a ‘stepping stone’ to move to Australia.

Australian species, however, are completely different; they evolved in a cooler and increasingly drier climate over time, making it difficult for them to establish themselves in tropical islands compared to migrating species from Asia,” Skeels explained.

Researchers hope that their model can be used to predict how modern climate change will affect various species.

It could help scientists forecast which species might adapt better to new environments as climate change is intensifying globally, impacting global biodiversity patterns.

This research was published in the journal Science in July.