On a day at the end of 1959 or 1960, four outstanding CIA agents worked through the night to disassemble the Soviet spacecraft Lunik that had been captured.

They photographed everything, documenting every structural detail, before perfectly reassembling the spacecraft without leaving a trace. This audacious espionage operation took place in the early years of the space race. The goal was to level the playing field between the two superpowers, but it also carried the risk of turning the Cold War into a hot war.

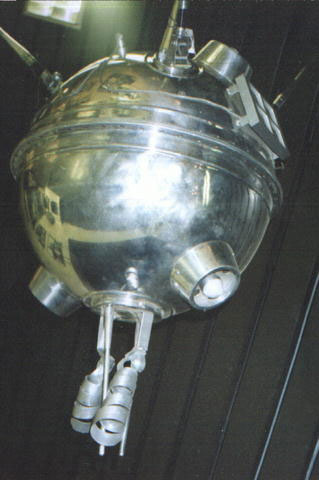

Luna 1 spacecraft of the Soviet Union eventually orbited the Sun. (photo: NASA).

On January 2, 1959, the Soviet Union launched the Luna program, referred to as Lunik by Western media, by launching Luna 1. Luna 1 did not reach the Moon, but the next spacecraft did reach its destination and became the first spacecraft to approach the Moon in September of that year. A month later, on October 7, Luna 3 sent back the first photographs in history of the far side of the Moon.

It was a glorious year for the Soviets in lunar exploration, while the achievements of the United States were limited to a few unsuccessful launches. This reality not only dealt a blow to national morale but also had a profound impact on the American psyche. No matter how excited Americans felt about space missions, they still faced the reality that their rival possessed larger rockets and more advanced technologies.

The technological gap between the United States and the Soviet Union sparked a CIA intelligence program. By studying Soviet spacecraft and their space flights, the CIA hoped not only to predict upcoming launches and increase public influence but also to adjust American launch plans to maintain a better pace than their rival. Even the insights from those familiar with Soviet plans could help the U.S. know where to focus efforts to surpass this nation in space. This intelligence operation would also prepare U.S. leaders to better respond to the Soviet Union.

The CIA’s intelligence operations focused on information that could be accessed remotely. This involved electronic intelligence, monitoring, and intercepting data to comprehensively gather information about Soviet space flights.

However, this was not without challenges. American agents had to accurately predict the timing of spacecraft launches, filter and search for information from afar. Post-flight analysis was also a crucial step. After obtaining the most comprehensive dataset possible regarding the altitude of the spacecraft, the target planet, and the landing points of each rocket stage after completing its mission, CIA agents would extrapolate calculations regarding the size and power of the launch vehicles. But all of this was just part of the equation, as space flights were not the same; each mission required extraordinary efforts to understand what was truly happening. At that moment, nothing was bolder or more visionary than the decision to kidnap Lunik.

The surface of the Moon photographed from Luna 3. (photo: NASA/Soviet Space Center).

From late 1959 to 1960, the Soviet Union organized a series of exhibitions showcasing its economic and industrial achievements in various countries. Among the exhibits were the Sputnik spacecraft and the upper body of Lunik, which had been freshly painted and equipped with observation windows at the nose of the craft. Initially, many CIA agents believed that the displayed Lunik was merely a model; however, some analysts expressed doubt, thinking the Soviets were proud enough to bring an actual spacecraft here. This suspicion was later confirmed when CIA intelligence agents attempted to approach Lunik one evening after the exhibition had closed. It was not a model. The agents were eager to examine the spacecraft more closely. They longed to explore inside Lunik.

But saying it was easy; doing it was difficult. Lunik was under tight security, making it impossible to study it before or after the exhibition closed. However, Lunik was also moved frequently, meaning it could be “temporarily borrowed” if there was a weak link. And indeed, there was a vulnerability. The spacecraft, along with all other exhibits, was packed in wooden crates before being transported by truck to the station, from where it would be moved by train to the next city. At the station, a guard recorded each crate being delivered and went home thinking he had completed his duty with the last shipment. A few CIA agents followed this individual throughout the night to ensure he did not arrive for work too early the next day.

Back at the old parking lot, the CIA agents drove through a narrow passage, closed the gate, and sealed off the area. They waited nervously for half an hour to ensure they were not being followed. Once they felt secure, the group shifted their focus to the main target of the evening. Earlier, they had thoroughly researched the crate, knowing that the sides were tightly sealed from the inside, meaning the only way to access Lunik was from the top. Two agents were tasked with finding a way to open the crate’s lid without leaving any traces on the wooden planks – fortunately, the crate had been opened and closed multiple times before, making the planks look worn – while the other two agents prepared to take photographs.

When the lid of the box was removed, the agents noticed that Lunik occupied almost all the space, meaning they could not move around inside the box. Therefore, the team was split in two; one half focused on the front section while the other half examined the tail of the spacecraft. The agents took off their shoes, used a rope ladder to climb down, and began exploring Lunik. They used an entire roll of film just to photograph the antenna before sending it for processing. They wanted to ensure that the cameras were still functioning properly. Fortunately, the returned information included perfectly clear photographs.

Two agents in charge of the tail section of the spacecraft removed the base to investigate the internal engine. Although the engine was not present, the mounting frames, fuel tanks, and oxidizer tanks were enough for experts to visualize the size and power of the engine. At the nose of the spacecraft, the agents discovered a rigid bar running along the body, secured by a four-way socket that resembled a screw. The socket was encased in a plastic component with a seal. This was the only ‘gateway’ to understand the inside of the spacecraft, but if the seal was broken, the Soviet guards would know that someone had tampered with their spacecraft. Unwilling to give up just because of a piece of plastic, the agents consulted with their colleagues at the CIA about whether the seal could be duplicated to reattach to the spacecraft in time. The confirmation from their colleagues gave them the confidence to cut the piece of plastic in half. The seal was then sent for duplication while the agents began to investigate the internal structure of Lunik.

Notably, during the operation, they had to unscrew nearly 130 four-sided screws and forge a Soviet seal. The agents worked through the night. By dawn, the team reassembled Lunik, trying not to leave any traces. They affixed the seal, closed the wooden box, and when the satellite was fully reassembled, it was placed back in the sealed box on the truck. The driver was returned to the cabin at 5 AM, and by 7 AM, when the guard started his morning shift, the truck was already waiting at the station. He had no suspicion and immediately added the box to his management list, while Lunik continued its journey to the next city.

According to the processed information received, the Americans realized that before them was the sixth lunar satellite manufactured (possibly the E-1A number 6 that was never launched). The collected data also helped the CIA identify three manufacturers of equipment for the Soviet space program, as well as many other details, the value of which to the American space program was still unknown or concealed in reports.

This abduction of Lunik by the CIA played a relatively important role. Knowing the dry weight and actual size of Lunik allowed experts to determine the weight of the spacecraft when fully fueled. From there, the Americans could calculate the actual power of the rocket, estimate the potential of the Soviet Union, and more importantly, determine the explosive mass limits according to current technology. Abducting Lunik helped the U.S. identify what the Soviet Union could not achieve without significant technological breakthroughs. This information was useful for American leaders and NASA heads to set reasonable goals and timelines to catch up with and ultimately surpass the Soviet Union in space.