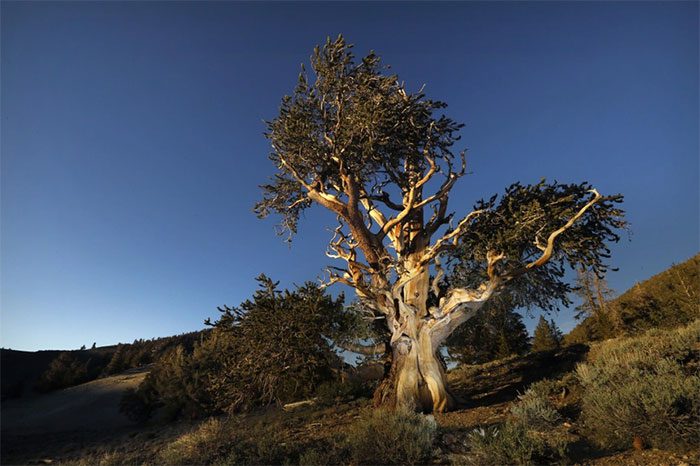

The bristlecone pines in California have survived for thousands of years, but now scientists are striving to keep them alive.

These ancient trees have stood tall here for over a thousand years. Their sturdy roots cling to the rocky mountainside, while their gnarled branches reach up into the desert sky.

The concentric rings within their trunks could tell humanity a chronicle of everything they have witnessed, every attack they have withstood, and every crisis they have endured.

The bristlecone pines in Death Valley National Park, California, have reached a “mythical” status among both the public and the scientific community. (Photo: LA Times).

Mass Deaths of Trees

Weather patterns change, empires rise and fall, other species are born, migrate, breed, and die. Yet in this part of California, one of the harshest environments on the planet, the bristlecone pines have always persisted. They seem to always survive.

Until one day in 2018, when Constance Millar hiked the trail to the summit of Telescope Peak—the highest point in Death Valley National Park—and discovered hundreds of bristlecone pines slowly dying. The horrifying sight extended as far as her eyes could see.

The needles on the trees turned a fiery orange, and the bark became gray like a ghost. Millar estimated that about 60-70% of the bristlecone pines at Telescope Peak had died.

“It felt like walking through the scene of a massacre,” shared Millar, an ecologist who has worked for the U.S. Forest Service for the past 40 years.

In a study published earlier this year, Millar and her colleagues concluded that over two decades of drought—considered the worst in 1,200 years in the western United States—had severely weakened the bristlecone pines.

Bark beetles, previously not a threat to healthy trees, now became a lethal blow to an immunocompromised population.

And after standing firm for millennia against disasters, these ancient trees are now unable to withstand the pressure of climate change driven by human activity. Scientists believe rising temperatures have led to a surge in harmful insect species, leaving the bristlecone pines unable to defend themselves.

While the bristlecone population in California’s Great Basin is not considered at risk of extinction, these particular individuals are struggling to survive.

In this crisis, bristlecone pines are not the only victims. Wildfires sweeping through Yosemite National Park threaten the survival of the giant sequoia population there.

Meanwhile, on the East Coast of the United States, cedar populations are also threatened by saltwater intrusion due to rising sea levels. Another rare oak species is struggling in the deserts of Texas as the weather becomes increasingly hot and dry.

A dead bristlecone pine in Death Valley National Park. (Photo: LA Times).

A new study published in mid-July in the scientific journal Nature shows that climate change has pushed nearly a quarter of the best-protected forests on Earth to a “critical threshold.” This is a point at which forests lose their ability to recover, and even a minor drought or heatwave can cause significant damage.

Standing amidst the deathly scene at Telescope Peak, Millar remarked: “This could be a harbinger of what may happen in the future.”

If bristlecone pines—considered some of the most resilient organisms in nature—cannot cope with climate change, what will happen to the rest of life on this planet?

And if humanity does not pay attention to these warning signs, what does that say about us?

Prehistoric Treasures

No other organism on Earth lives as long as the bristlecone pines in the Great Basin. The oldest tree here is named “Methuselah”—after the longest-lived character in the Bible.

When the ancient Egyptians began constructing their pyramids over 4,500 years ago, Methuselah was already a young pine. Even the relatively younger bristlecone pines in Death Valley were born before gunpowder, paper money, or the English language.

The secret to the bristlecone pines’ longevity is their ability to endure what other organisms cannot.

They thrive at higher altitudes than most other trees, flourishing in rocky, rugged terrain on steep mountains. Their fibrous root systems and tiny leaves help them make the most of the scant water available in this environment.

Moreover, the resin from their trunks is highly viscous, trapping insects that intrude, and enabling the trees to quickly heal wounds. The bristlecone pine’s genome is nine times longer than that of humans, containing numerous mutations that allow them to adapt better when environmental conditions change.

Few tree species have such resilience as the bristlecone pine. If conditions become too challenging, an individual tree will self-prune some branches, allowing the rest of the tree to continue to survive. The wood of the pine is so dense that it rarely rots. Even dead trunks can stand for hundreds of years.

This species truly requires such “supernatural” abilities to survive in Death Valley. This national park lies further south than any habitat of bristlecone pines, with higher temperatures and lower humidity than anywhere else in the United States.

The bristlecone pines help researchers better understand what has occurred on Earth over thousands of years. (Photo: AP).

Many other organisms also benefit from the bristlecone pines, providing shade for mule deer and bighorn sheep, while serving as shelter for chipmunks and rabbits from predators and harsh weather. These trees also help snow remain longer in the high mountain slopes of the park, retaining water for the brutal summer months.

Having lived for thousands of years, the data that bristlecone pines carry within them becomes invaluable to scientists. The annual rings in their trunks allow them to reconstruct climate records from millennia ago.

This is a new field known as dendrochronology—the science of studying the age of trees. The rings in the trunks can reveal when volcanic eruptions occurred, how long droughts lasted, or when solar storms took place.

Genetic Loss

In addition to recording what has happened, bristlecone pines also provide a key to understanding our future. They capture the interactions between greenhouse gases, rising temperatures, changing weather patterns, and ecosystems, allowing scientists to predict what happens as the Earth warms.

“The loss of these individuals could mean the disappearance of a natural data repository. I hope the public will realize how significant this loss is,” Millar shared.

Although bristlecone pines are not classified as endangered, Millar believes the death of some populations is still very regrettable. Each tree that disappears is not only a loss to the landscape but also a loss in genetic diversity.

Millar recalls another trip to Death Valley when she had to hike a long distance to reach an area where a population of bristlecone pines still lived. She only found one remaining tree, and it had just died.

After thousands of years of existence in one of the harshest environments on the planet, the bristlecone pines are now under threat. (Photo: AP).

If this tree possessed a gene that allowed it to survive in this harsh environment, there would be no chance to revive that gene. There is also no hope of replanting the tree from seeds or cutting a segment for asexual propagation. In other words, scientists have lost the opportunity to help other bristlecone pines survive.

“To me, witnessing a population go extinct is horrifying. All that unique genetic material, the product of thousands, if not millions, of years of evolution, has vanished forever,” Millar said.