Few people know that to conduct what is now a commonplace procedure like blood transfusion, scientists have invested considerable effort and undertaken numerous risky experiments…

The successful blood transfusions began in the 19th century and gained momentum in the 20th century. The story of the emergence of the field of hematology and blood transfusion is intertwined with thrilling experiments that resulted in the deaths of many individuals.

Daring Ideas and Deadly Experiments

The idea of blood transfusion first appeared around the mid-17th century, introduced by prominent physicians of that era and recorded by a man named Stefano Infessura. According to the records, in 1492, when a prominent figure fell ill and lapsed into a coma, the blood of three young boys was used by physicians to transfuse into the pope orally.

At that time, people did not have a clear understanding of the blood circulation process or the principles of blood transfusion; they merely regarded blood as a vital element sustaining human life. The boys selected for blood donation were only around 10 years old, and after a significant amount of blood was drawn for the pope, they tragically succumbed to blood loss.

In 1660, following William Harvey’s discovery of the blood circulation laws within the body, surgical experts in London, England, and Paris, France, began conducting blood transfusion experiments from calves and sheep into dogs, or from dogs into cows, or from goats into horses… However, the most notable experiment was a trial transfusion from sheep to a human. The participant chosen for this sheep blood transfusion was an Englishman named Arthur Coga.

The experiment was deemed successful by the scientists of the time, as the patient Arthur Coga managed to recover for a short period before ultimately passing away.

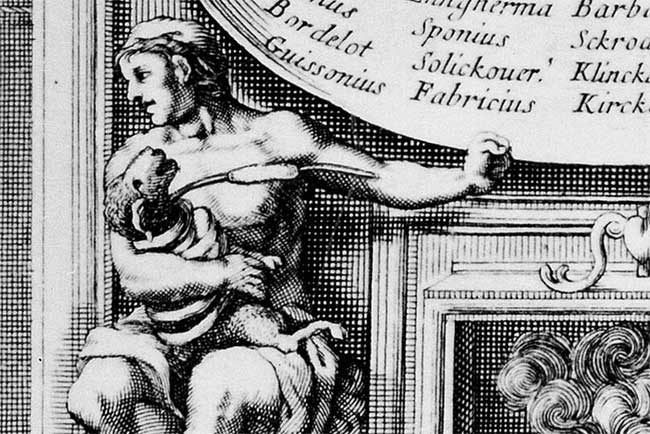

Blood transfusion experiments conducted on animals and between animals and humans.

After this audacious trial and Coga’s death, in 1667, refusing to abandon their hopes, the surgeons in London and their French colleague, Dr. Jean Baptiste Denis, continued with another experiment.

Dr. Denis simultaneously conducted a blood transfusion from a young sheep to a seriously ill 16-year-old boy and another transfusion from a calf to a patient named Antoine Mauroy.

Unfortunately, all of his patients died. For a long time after these blood transfusion experiments yielded no positive results for humans, there was a reluctance to undertake any further risky transfusion trials.

Success After 150 Years of Waiting

The first success in human blood transfusion truly came in the early 19th century. At that time, science had not yet discovered blood types. The brave individual who successfully conducted this experiment was obstetrician James Blundell, from England.

In 1818, Dr. Blundell performed a transfusion using blood from a husband of a woman suffering from postpartum hemorrhage to save her life, achieving unexpected success. Following this achievement, from 1825 to 1830, Dr. Blundell conducted 10 blood transfusions.

Five of those ten transfusions resulted in remarkable recoveries for the patients. Dr. Blundell also invented the blood transfusion apparatus that is still in use today.

Dr. Blundell performed a transfusion using blood from a husband of a woman suffering from postpartum hemorrhage to save her life, achieving unexpected success.

Following Dr. Blundell’s success, the field of hematology and blood transfusion truly flourished and achieved continuous advancements. In 1840, at George Medical School in London, with Dr. Blundell’s assistance, a student named Samuel Armstrong Lane conducted a life-saving blood transfusion for a patient suffering from hemophilia. However, the success rate of blood transfusions remained very low, heavily reliant on chance.

It wasn’t until 1901 that Austrian scientist Karl Landsteiner discovered blood types. This discovery is considered a significant milestone in science, as it enabled scientists to achieve what they had struggled with for two centuries and opened new avenues for the development of hematology and blood transfusion.

Matching the correct blood type is crucial in blood transfusions.

At this point, it became clear that the failures of previous experiments were due to the transfused blood not being accepted by the patient’s body and being rejected due to incompatible blood types. Thus, ensuring the correct blood type match is vital in blood transfusions.

Blood transfusion has become much safer, and the risk of death during transfusion has nearly vanished. Thanks to this important discovery, Karl Landsteiner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 1930.