While there is hope that the boom in electric vehicles and green energy will bring wealth, the people of this country remain apprehensive about past failures.

The Potosí Mountains in southern Bolivia were once among the richest locations in the Spanish Empire. In the 16th and 17th centuries, more than half of the world’s silver originated from a mountain in this region. The seemingly barren landscape of Potosí has since yielded many other valuable minerals, including aluminum, lead, and zinc.

In the 19th century, a British company built a railway to transport minerals from Bolivia to the Chilean coast, from where they were shipped to Europe. Potosí, with its railway junction connecting Bolivia’s administrative capital La Paz to Chile and Argentina, remains an important transportation hub.

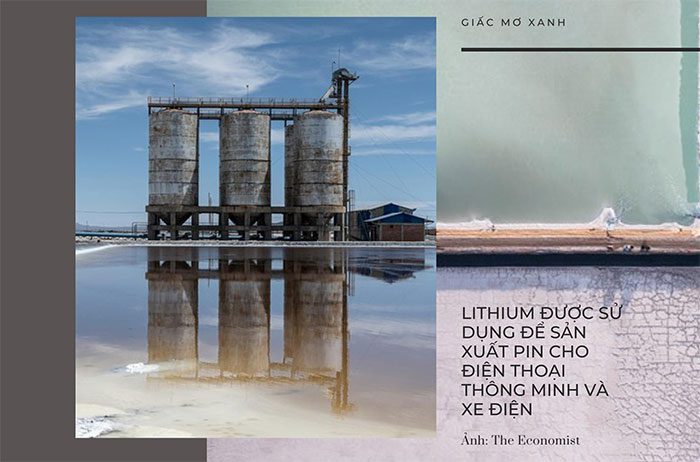

Lithium is a lightweight and soft metal used in batteries for smartphones, electric vehicles…

However, the wealth generated from the land of Potosí over the centuries has hardly remained in Bolivia. Potosí is the poorest region in Bolivia, and Bolivia is the second poorest country in South America.

More than two-thirds of Potosinos live in homes made of brick or mud. During the rainy season, when the red clay turns to mud, the unpaved roads in the area become impassable.

The local population lacks adequate healthcare, and children do not have consistent access to education. One-quarter of women still give birth at home. Nearly 40% of adults have only completed elementary school, and 20% have never been to school.

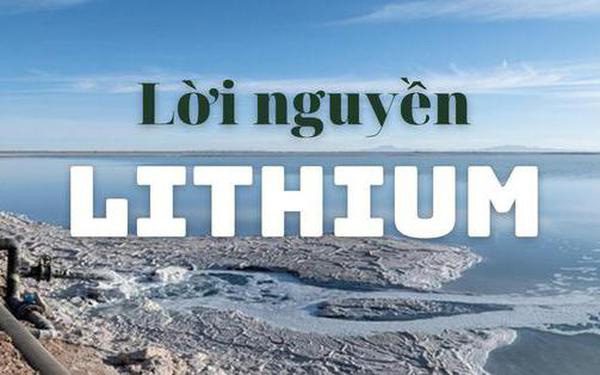

The poverty in Potosí is even more striking considering that it is home to the largest lithium deposit in the world. Lithium is a lightweight and soft metal used in batteries for smartphones, computers, and electric vehicles.

This mineral was discovered in the Uyuni salt flats in the 1970s. As the world shifts towards greener energy sources, this mineral has become increasingly sought after.

In search of profit from this rising demand, in 2013, the Bolivian government opened a lithium production plant on a corner of the salt flats. The solid white land stretches over 10,000 square kilometers atop the Andes, one kilometer higher than the neighboring Peruvian town of Machu Picchu.

The surrounding communities, which were already the wealthiest in Potosí, have yet to see any benefits from the mineral extraction. In many respects, their lives have become more difficult than ever.

Tourism, a source of income for many, dried up during the pandemic. Climate change has led to severe drought. As a result, traditional industries such as quinoa farming and llama herding have become precarious.

Some locals scrape by with meager earnings from salt. Harvesting salt is a labor-intensive process involving a truck, a tractor, and men wielding shovels, dressed in long sleeves to shield themselves from the harsh sun.

However, it no longer rains as much as it once did. Consequently, the annual layer of salt crystals is no longer as thick as before. Locals worry that the water-intensive process of lithium production will exacerbate the region’s water scarcity.

If Potosí is looking to escape poverty, its best bet is its nascent lithium industry. But can it avoid being exploited, as has happened so many times before?

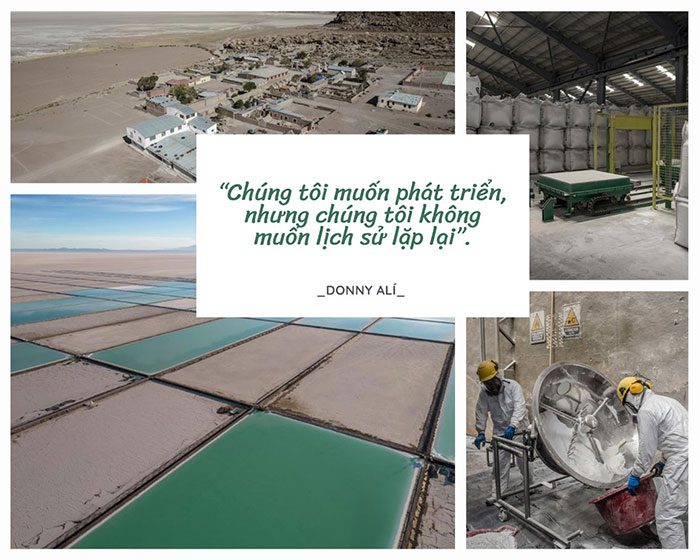

Donny Alí, 34, a lawyer and hotel owner in Rio Grande, a town of about 2,000 people on the southern edge of the salt flat, stated: “We want to develop, but we don’t want history to repeat itself.“

Alí recalls his parents teaching him as a child “not to trust any foreigners talking about our natural resources.” Greedy foreign companies permitted by the Bolivian government have rapidly developed, leaving Alí’s town impoverished for centuries.

In the 1990s, his family opposed the government’s decision to grant exclusive mining rights to the Canadian company LitCo for the entire salt flat area. Once again, it seemed the local community would lose everything. Thanks to their protests, the contract was eventually revoked.

Alí and his seven siblings were among the first residents of Rio Grande to attend university. He credits their education to their mother, who dropped out at seven to support the family by selling street food. She convinced her husband, a railway porter, to move the family to Uyuni, a larger town on the other side of the salt flat, where there was a high school unlike Rio Grande.

All seven siblings attended university in the nearby city of Sucre. At one point, six of them were crammed into shared accommodations. Each week, they received a package containing quinoa, bread, and jerky from relatives in Rio Grande, where staple items were cheaper.

It was a hopeful time in Potosí. Former President Evo Morales, who led Bolivia from 2006 to 2019, banned foreign companies from controlling shares in the mining sector. Instead, he pledged to help Bolivia create its own lithium industry.

In 2013, when the lithium processing plant opened on the outskirts of Rio Grande, locals were thrilled that their town was becoming “the epicenter of the white gold industry.”

As a member of the town council at that time, Alí helped negotiate a deal with the state-owned lithium company Yacimientos de Litio Bolivianos. The plant would have access to water supplies from the village in exchange for locals from Rio Grande becoming truck drivers transporting lithium carbonate and potassium chloride.

Planta Llipi is described as a massive complex surrounded by a high metal fence. The plant buildings, warehouses, laboratories, and 160 white salt ponds are spaced far enough apart for trucks to drive around.

When the plant opened, optimists believed that lithium would help usher Bolivia into the modern world, creating jobs and developing the region.

Many families in Rio Grande formed a cooperative, purchasing trucks in anticipation of a lithium boom. They believed they would also be transporting other goods besides lithium from nearby bauxite and ulexite mines. (Bauxite, essentially red mud, is used in industrial chemicals and construction materials. Ulexite contains boron, used in fertilizers and fiber optics).

In Rio Grande, construction also boomed. New homes sprang up. A modern town hall with large windows was built. A school and a stadium were also newly constructed. Alí built a two-story hotel on a busy street and named it Lithium. He also opened a store for future guests to buy snacks.

However, turning lithium into gold proved to be an unprecedented challenge.

Although the truck drivers’ association has helped Rio Grande prosper more than surrounding communities, contracts with the state lithium company have yielded less profit than the drivers had hoped.

Some of them drive trucks carrying lithium carbonate between buildings within the plant. But drivers from elsewhere often get preferential treatment for trips to major cities like La Paz and Santa Cruz, where potassium chloride and lithium carbonate are exported.

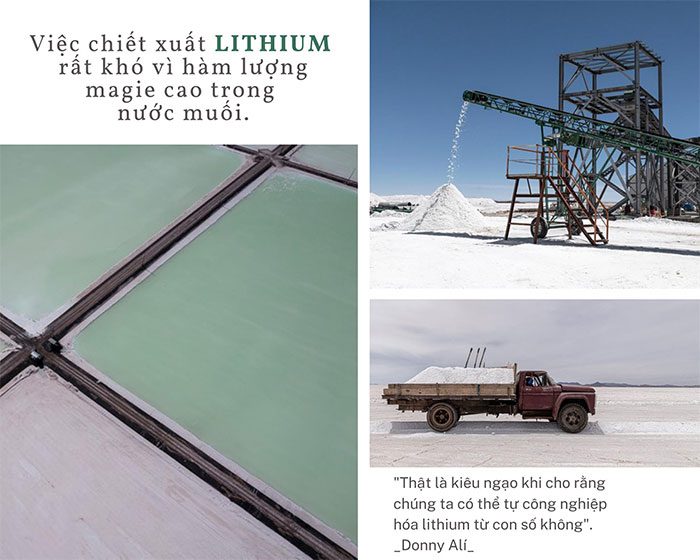

The foreign entrepreneurs Alí hoped for have yet to arrive. The plant produced 600 tons of lithium carbonate in 2021, while Chile and Argentina produced 134,000 and 36,000 tons, respectively. Lithium extraction is highly complex, especially in Bolivia, due to the high magnesium content in the brine and, more importantly, the lack of local expertise.

This is one reason why the jobs locals hoped for have not materialized. Natalio Cayo, a former mayor of Chuvica, a village near the salt flats, stated that in 2020, the government asked him to create a list of villagers suitable for jobs at the plant. However, those he recommended have yet to be contacted. Cayo remarked that it was naïve to think lithium would provide jobs for many locals.

In recent years, half the people in his village have left to seek work. On the dusty roads, weeds grow from abandoned vehicles.

Rio Grande has plans to build a new high school specializing in chemistry, hoping to train a new generation to work in the lithium industry. Truck driver Jonas, Alí’s cousin, expressed his desire to see his two sons wearing lab coats in a laboratory. He said: “I never had the chance to get an education.“

However, building a workforce with the right skills will take a significant amount of time. This is a reality that Bolivian President Luis Arce has acknowledged since 2020. Unlike his predecessor Morales, Arce aims to build partnerships with foreign companies that can help develop technology to enhance production.

Donny Alí, like many others in Rio Grande, has come up with the idea of foreign investment. He said: “It’s arrogant to think we can industrialize lithium from scratch.“

In 2021, Alí moved to La Paz to work on lithium policy for the national energy ministry, following the government’s concession to local demands for representation in the federal government. However, just a year later, he resigned and returned to Rio Grande, disheartened by the lack of progress.

He remains concerned that Bolivia may repeat the mistakes of the past. He believes that local communities must be consulted before any agreements are signed, and they deserve to share royalties fairly. Meanwhile, his Lithium Hotel remains empty.