The Solar Orbiter spacecraft has sent back to Earth the highest resolution images of the Sun’s surface to date, revealing many mysteries of our star.

On November 20, the European Space Agency (ESA) shared four images taken by the Solar Orbiter spacecraft in March of last year, when the spacecraft was 74 million kilometers away from the Sun. These images capture the intricate and textured surface of the Sun known as the photosphere, the layer that emits the light we see.

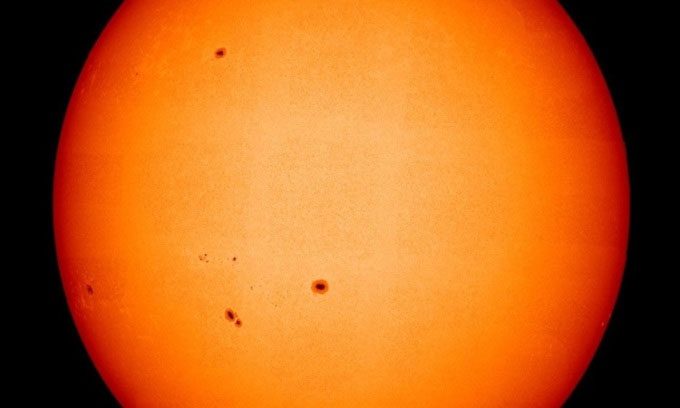

The sunspots on the smooth surface of the Sun. (Image: ESA).

The Polarimetric and Helioseismic Imager (PHI), one of six instruments aboard the spacecraft, captured the scattered particles on the surface. These are large, chaotic plasma cells, each spanning about 1,000 kilometers. They are created by convection, the process by which hot plasma rises from below while cooler plasma sinks from above, similar to bubbles forming and rising in a pot of boiling water. These cells cover the entire surface of the Sun, except for the sunspots, which are darker, cooler areas that appear like blemishes on the smooth photosphere.

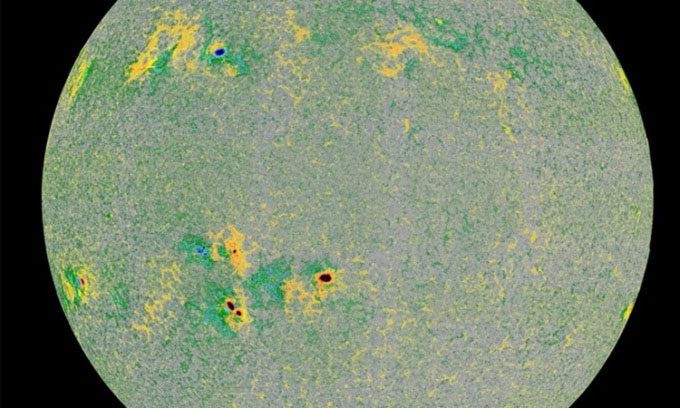

The image below shows a new map of the Sun’s magnetic field, also from PHI. It reveals a particularly strong and concentrated magnetic field in the sunspot regions. This helps explain why the sunspots are cooler than their surroundings. The extremely strong magnetic field in these areas restricts the normal convection process of plasma, forcing material to move along the magnetic field lines. As a result, some of the heat cannot reach the surface, making the sunspots cooler than other areas on the Sun’s surface, according to Daniel Müller, ESA’s Solar Orbiter project scientist.

The direction of the magnetic field on the Sun’s disc. (Image: ESA).

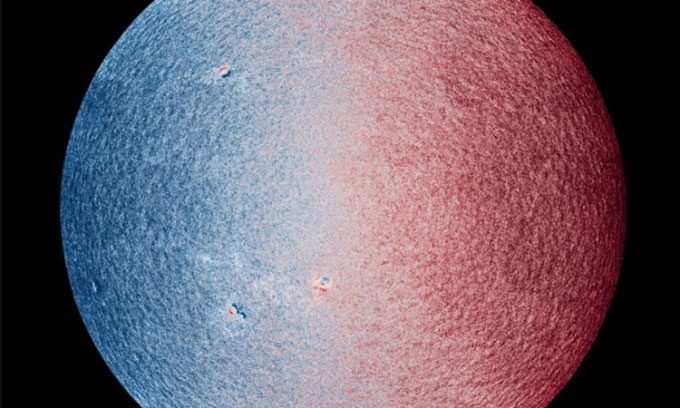

Another new map called a tachogram shows the speed and direction of material moving on the Sun’s surface. The blue region is moving towards the Solar Orbiter while the red region is moving away, revealing the Sun’s rotation around its axis. The solar wind escaping from the outer atmospheric layer known as the corona was also captured in March of last year using the Extreme Ultraviolet Imager (EUI) on the Solar Orbiter.

A map of the direction and speed of material on the Sun’s surface. (Image: ESA).

The Solar Orbiter is currently 120 million kilometers from the Sun, beyond the orbit of Venus. Together with NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, the spacecraft has recently provided new insights into the heating and acceleration processes of the solar wind to incredible speeds in space. The probe, launched in 2020, is part of a collaborative mission between Europe and NASA aimed at capturing unprecedented images of the Sun’s poles. By early 2025, the spacecraft’s orbit will allow it to achieve a higher inclination angle and directly observe the Sun’s poles.