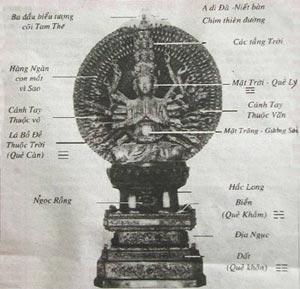

The famous statue of Avalokiteshvara, known as the Thousand Eyes and Thousand Hands, at But Thap Pagoda encompasses many “hidden meanings” and profound philosophies. It reveals much about the aesthetic perspective, worldview, and cosmic view of the Vietnamese people during the Later Le Dynasty in the latter half of the 17th century.

The famous statue of Avalokiteshvara, known as the Thousand Eyes and Thousand Hands, at But Thap Pagoda encompasses many “hidden meanings” and profound philosophies. It reveals much about the aesthetic perspective, worldview, and cosmic view of the Vietnamese people during the Later Le Dynasty in the latter half of the 17th century.

The statue of Avalokiteshvara at But Thap Pagoda in Bac Ninh was carved by Truong Tho Nam and completed in 1656 during the Later Le period. The pedestal of the statue bears the inscription: Nam Dong Giao, Tho Nam – Truong Xuan – phung khac (interpreted as: Nam Dong Giao refers to the location, Tho Nam is the courtesy name, Truong is the family name, and phung khac means to carve as commanded by heaven and earth). According to some researchers, the phrase “phung khac” is translated as carving according to the emperor’s wishes (however, if it were carved at the behest of the emperor, the statue would be located in the capital, whereas this statue is enshrined in a pagoda).

The statue of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion – commonly known as the Thousand Eyes and Thousand Hands, can be seen as a miniature universe, crafted according to a very strict system of rules. These rules reflect the principles of yin-yang, the five elements, and the eight trigrams, which always encompass pairs of opposing yet unified categories: Yang – Yin (good – evil, red – black, light – dark, heaven – earth). To help readers recognize these opposing aspects in the composition of Truong Tho Nam’s work, the following analysis is presented:

1. The Avalokiteshvara statue is designed according to the concept of the Three Powers, which represents the harmonious relationship between heaven, earth, and humanity. When observing the statue, the circle behind it is adorned with nearly a thousand hands, each hand carved with an eye, symbolizing Heaven. Here, Heaven is perceived as a miniature universe. In this universe, goodness is represented by the concept of “three illuminations,” which include the sun, moon, and stars.

Since ancient times, the Vietnamese have recognized the sun as the center of life, its miraculous power depicted at the center of the Dong Son bronze drum. In this statue, the artist has also placed the face of Avalokiteshvara at the center of the statue. The sun is  the most prominent, radiant face of Avalokiteshvara, full of compassion and benevolence. The sun here is represented as a dawn, with rays shining upward rather than spreading sideways, implying that goodness is on the rise, possessing the power to conquer, symbolizing social civilization. The brilliant sun also symbolizes the wisdom of Avalokiteshvara spreading everywhere to dispel darkness. Those with obscure behaviors cannot hide from the eyes of the Buddha. To express this profound meaning, the artist has carved an eye in the palm of a hand, symbolizing the thousands of stars in the galaxy. All numbers on the statue are odd numbers, with over 900 hands and more than 900 eyes. The artist believes that the number 1,000 is even, yin, static, and non-developing. Odd numbers are dynamic, yang, and continuously evolving. This means that in the universe, countless stars are observing the earthly realm.

the most prominent, radiant face of Avalokiteshvara, full of compassion and benevolence. The sun here is represented as a dawn, with rays shining upward rather than spreading sideways, implying that goodness is on the rise, possessing the power to conquer, symbolizing social civilization. The brilliant sun also symbolizes the wisdom of Avalokiteshvara spreading everywhere to dispel darkness. Those with obscure behaviors cannot hide from the eyes of the Buddha. To express this profound meaning, the artist has carved an eye in the palm of a hand, symbolizing the thousands of stars in the galaxy. All numbers on the statue are odd numbers, with over 900 hands and more than 900 eyes. The artist believes that the number 1,000 is even, yin, static, and non-developing. Odd numbers are dynamic, yang, and continuously evolving. This means that in the universe, countless stars are observing the earthly realm.

2. Above, there is heaven, represented by a circle, dynamic, and belonging to yang; thus, the earth is represented below, static, and belonging to yin; the square shape connects heaven and earth through humanity – the figure of Avalokiteshvara. Heaven, earth, and humanity represent three supernatural forces in the universe, possessing endless creative power. The black dragon beneath the lotus throne symbolizes evil. The Thousand Eyes and Thousand Hands statue of Avalokiteshvara sits upon the lotus throne, which is placed on the head of the black dragon, symbolizing that goodness always prevails over evil. The dragon’s two arms merely support the lotus throne, creating a cohesive composition, implying that evil also possesses extraordinary power, as a single head is enough to elevate the entire statue. On Avalokiteshvara’s crown are three tiers, each with three heads, with the ninth head being Amitabha Buddha – symbolizing the Pure Land of Nirvana. Thus, each head symbolizes a layer of heaven. Interestingly, Amitabha Buddha and the celestial bird behind are associated with two heads (the number 2 belongs to yin, symbolizing the souls of the deceased who have transcended to the Pure Land). The three heads converge to evoke the concept of the three realms: “past – present – future.”

3. In temples, the three figures of the three realms are always placed at the highest point. In the art of composition, Truong Tho Nam has interconnected the phenomena into a symbol: The large circle behind is connected to the celestial bird, forming the image of the Bodhi leaf, with the heart of the Buddha as the stem of the leaf. Buddhism uses the Bodhi leaf as a symbol. The image of the moon is placed before the Buddha’s heart as a mirror to reflect upon one’s actions daily, whether right or wrong, good or evil, light or dark… Above lies the Pure Land, the abode of Amitabha Buddha, while below is hell, depicted in the four corners by four plump figures suffering punishment, intended to deter anyone with malicious intent.

4. In the composition of this statue, the arms are arranged in a complex yet consistent manner according to the principles of expression. There are three fundamental methods to express the meaning of the hand positions: First, two hands clasped before the chest symbolize the human will and intention to do good. Second, the 42 arms attached to the sides of the statue radiate in multiple directions, implying that to overcome evil, one must employ both intellect and strength (the arms on the right symbolize intellect, while those on the left symbolize strength). Third, the hand of Avalokiteshvara cradles the moon before her heart, symbolizing introspective examination. To cultivate and attain enlightenment, sentient beings must have patience, practicing over lifetimes; the longer they nurture virtue, the greater the blessings. The two hands resting on the Buddha’s thighs symbolize unwavering determination to achieve results.

4. In the composition of this statue, the arms are arranged in a complex yet consistent manner according to the principles of expression. There are three fundamental methods to express the meaning of the hand positions: First, two hands clasped before the chest symbolize the human will and intention to do good. Second, the 42 arms attached to the sides of the statue radiate in multiple directions, implying that to overcome evil, one must employ both intellect and strength (the arms on the right symbolize intellect, while those on the left symbolize strength). Third, the hand of Avalokiteshvara cradles the moon before her heart, symbolizing introspective examination. To cultivate and attain enlightenment, sentient beings must have patience, practicing over lifetimes; the longer they nurture virtue, the greater the blessings. The two hands resting on the Buddha’s thighs symbolize unwavering determination to achieve results.

5. The statue of Avalokiteshvara emerged in a historically ripe context: The artist Truong Tho Nam absorbed and elevated the art of this statue to new heights through interaction with Indian sculpture and Cham sculpture, particularly the arms of the Buddha resembling the pure arms of Cham dancers. Avalokiteshvara’s attire is transformed into a sculptural form, with romantic lines and composition in the Vietnamese style that he absorbed from the Ly-Tran art through the depiction of the lotus. The lotus during the Ly dynasty was carved with dragons on its petals, while the lotus during the Le dynasty was sculpted with the flames of the Le tradition of resisting foreign invasions.

In Asia, Buddhism gave rise to the theme of “Thousand Eyes and Thousand Hands,” which has been carved in several countries, but the work by the genius sculptor Truong Tho Nam is renowned for its comprehensive content regarding the worldview and human outlook from the perspective of traditional Buddhism, achieving a remarkable artistic form. This statue received a special prize at the International Buddhist Art Exhibition in India in 1958.

Artist, Sculptor Le Dinh Quy