Among the individuals believed to have the rarest diseases in the world, particularly in the UK, is journalist David Rose. David suffers from a condition known as Occipital Horn Syndrome (OHS). According to global medical literature, there are currently only about 20 known cases of this disease.

David Rose, also known as David Edward Rose, is 34 years old and hails from Cambridge, England. He works for the Rare Revolution Magazine (RRM), a publication focused on rare diseases. Despite his unique condition, David remains actively engaged in his work and participates in speaking events to raise community awareness regarding this rare disorder.

Using his writing as a tool, David encourages others facing similar challenges and motivates the community to support those in need for a better quality of life.

According to David, when he was just 18 months old, he was taken to Great Ormond Street Hospital to treat recurrent bladder infections. It was later discovered that the issue was not related to his internal organs, and he was diagnosed with Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome, a group of disorders affecting connective tissue.

“The relentless infections plagued David Rose,” which led doctors to remove one of his kidneys when he turned 21. It was during this time that doctors recognized that David “did not meet the criteria for Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome” but was more accurately diagnosed with Occipital Horn Syndrome.

Journalist David Rose (center), the only person in the UK diagnosed with OHS, being interviewed by RRM in September 2021. (Photo: Ar.linkedin)

Since there is no known cure, David must take medications similar to those prescribed for Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome. Additionally, he has been using a catheter for the past 24 years, undergoing physical and occupational therapy, while relying on antibiotics to treat infections and other medications to manage bladder spasms.

Despite his illness, David Rose remains optimistic and works diligently to live a “normal” life, as he describes. Through his articles, David continuously encourages others with rare diseases to maintain a positive outlook and cherish life to lessen the burden on their families, loved ones, and society.

What is Occipital Horn Syndrome?

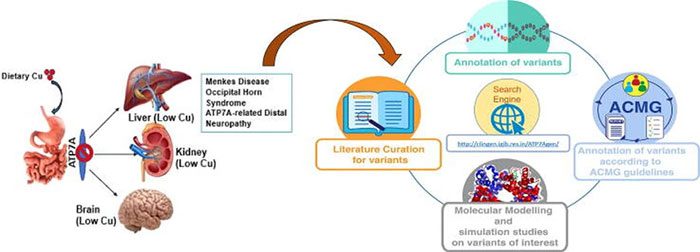

Occipital Horn Syndrome (OHS) is a connective tissue disorder and an X-linked recessive mitochondrial disease, typically occurring in early childhood. It is caused by a deficiency in copper transport, particularly related to ATP7A gene mutations.

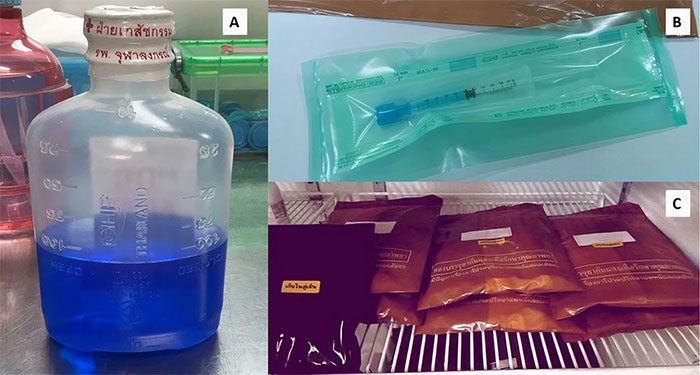

Currently, there is no specific treatment for OHS; early-life administration of histidine or copper chloride injections may help improve the condition in children. (Photo: Casereports.bmj)

About two-thirds of children with OHS are believed to have a genetic disorder; the remaining one-third do not have a family history of the disease. Since this disorder is caused by a recessive gene linked to the X chromosome, it affects more males than females. Females are more likely to be carriers of the disease. For a woman to be affected, she must have two defective X chromosomes rather than just one.

The hallmark of OHS is a deficiency in copper excretion through bile, leading to skeletal deformities. These include protrusions at the back of the skull (protrusions of the parasitic bones arising from the occipital bone, referred to as “occipital horns”), as well as deformities of the elbows, radial head dislocations, hammer-like clavicles, and abnormalities of the hips and pelvis.

OHS manifests in early to mid-childhood. Children may present with features such as intellectual development delays, long necks, high palates, elongated faces, high foreheads, loose skin, “double-jointedness,” inguinal hernias, vascular twists, bladder diverticula, loss of autonomic control, chronic diarrhea, coarse hair, low ceruloplasmin levels (9-29 mg/dL), central nervous system damage, and muscle weakness.

OHS – a genetic disease inherited in an X-linked recessive manner from the mother. (Source: Europepmc)

OHS has a later onset and is associated with much less severe central nervous system degeneration. The milder nature of OHS is often due to connector mutations that allow for 20-30% of the ATP7A messenger RNA to be processed correctly. Initial diagnosis is based on clinical symptoms.

Low serum copper and ceruloplasmin levels support clinical suspicion of OHS but require biochemical confirmation in tissue culture. Definitive diagnostic evidence is attributed to the ATP7A gene. The expression of bony protrusions on the occiput aids in diagnosis and may be palpable in some patients.

The long-term natural history of OHS is not well understood. Some patients have died suddenly at the age of 17, while one patient survived to 57 years old. Causes of death include respiratory failure, aortic aneurysm, and intracranial hemorrhage.

Treatment for OHS in children depends on the severity of the disease. Children with OHS often undergo physical and occupational therapy. Patients may require feeding tubes to supplement nutrition if they do not develop adequately.

In an effort to improve neurological conditions (seizures), histidine or copper chloride injections may be administered in early childhood. However, copper histidine injections have proven ineffective in treating the connective tissue manifestations of OHS.