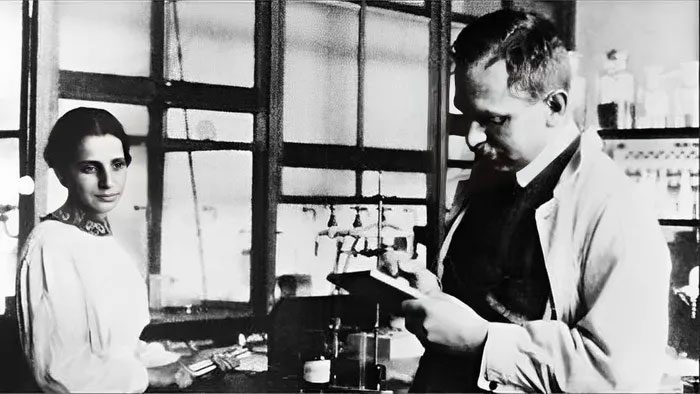

Lise Meitner was a distinguished physicist who made significant contributions to the field of nuclear physics, particularly in her groundbreaking work on nuclear fission.

Her accomplishments reflect an extraordinary effort as Meitner faced gender and racial discrimination throughout her life and career.

“Germany’s Marie Curie”

Lise Meitner is recognized as one of the greatest female scientists of all time.

The scientist Albert Einstein affectionately referred to Meitner as “our Marie Curie,” according to The Washington Post.

Lise Meitner was born in Vienna, Austria, in 1878. Her father was a lawyer, and her mother came from a prominent Jewish intellectual family. Meitner was the third of eight children in her family. From a young age, she showed a talent for mathematics and science, always receiving encouragement and support from her parents.

Meitner began her formal education at a girls’ school in Vienna. Despite her exceptional talent and endless passion for mathematics and science, she was denied admission to the University of Vienna because women were not allowed to attend at that time. However, with the help of her family and support from influential figures, Meitner eventually realized her dream of attending university, majoring in physics and mathematics.

She earned her Ph.D. in physics in 1905, becoming the second woman to achieve this distinction at the university.

Meitner then became an assistant to the physicist Max Planck, the founder of quantum mechanics and one of the most prominent physicists of the 20th century. Here, Meitner began to establish herself as a respected researcher in the field of physics.

49 Nobel Nominations, All Unsuccessful

Meitner faced severe gender discrimination throughout her career. Despite her achievements and talents, she was often paid less than her male colleagues and encountered barriers to career advancement.

When Meitner applied for a full professorship in 1917, she was rejected because university officials believed that physics was not a suitable subject for women.

However, Meitner did not let these injustices deter her. She continued to work diligently and pursue her passion for physics, ultimately becoming a professor of physics at the University of Berlin in 1926.

She also established a close collaborative relationship with Otto Hahn, a chemist who later became her partner in discovering nuclear fission reactions.

She and her collaborator Hahn discovered nuclear fission reactions, but only Hahn received the Nobel Prize.

Meitner and Hahn’s work on discovering nuclear fission reactions was groundbreaking, but she faced significant challenges in being recognized for her contributions.

In 1938, Meitner was forced to flee Nazi Germany due to her Jewish heritage. Later, Hahn received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1944 for discovering nuclear fission, while Meitner was not mentioned.

Meitner’s exclusion from the Nobel Prize is believed to be due to her gender and Jewish heritage. At that time, women and Jews were often not recognized in scientific fields, and Meitner’s exclusion from the award further reflects the discrimination and prejudice she faced throughout her career.

According to statistics from the American Nuclear Society (ANS), Meitner was nominated for the Nobel Prize 49 times over 43 years (1924-1967), including 30 times for Physics and 19 times for Chemistry. Ten countries nominated her, including Denmark, France, Germany, India, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Sweden, the United Kingdom, and the United States. However, Meitner never received a Nobel Prize for her work.

Despite these barriers, Meitner continued to work and made significant contributions to the field of physics. After leaving Germany, she settled in Sweden and continued her research in nuclear physics. She also became a mentor to many young physicists, including future Nobel laureate Hans Bethe.

Meitner missed 49 Nobel nominations despite her significant contributions to science.

Meitner’s work on nuclear fission has important implications for both science and society. The discovery of nuclear fission reactions paved the way for the development of nuclear energy and atomic weapons, profoundly impacting global politics and society.

Meitner was acutely aware of the potential dangers of nuclear weapons and strongly advocated for nuclear disarmament later in her life. Her legacy continues to be honored today. In 1997, element 109 on the periodic table was named Meitnerium in her honor.

Lise Meitner’s perseverance and dedication to her work serve as a tremendous inspiration, and her legacy has paved the way for generations of women pursuing careers in science.