Just like a sovereign nation with airspace above its territory, our brains also unconsciously create such buffer zones. It claims ownership of a space that extends beyond our skin.

Surely, you have experienced a situation where your personal space is severely invaded: parents suddenly entering your room without knocking, standing shoulder to shoulder on a crowded bus, or an unfamiliar elderly woman approaching you at a restaurant with a basket of chewing gum in hand…

However, the sense of personal space is something even more sensitive, to the point where your subconscious can vaguely feel when it is being stolen.

Try to recall your school days; we all know exactly when an invigilator is approaching us during an exam. While writing smoothly in a literature test, the teacher sneaks up behind you to peek at your paper. At that moment, you suddenly feel flustered and unsure of what to write next.

This sense of privacy follows us as we grow up, helping you know when someone is glancing at your phone in the elevator, when someone at the gym is paying attention to you, and again, when your boss is watching you work from behind.

“Our unconscious understanding of personal space is not only a fundamental means of self-protection. It is also one of the influences that shape us [throughout our lives], determining behavior between individuals and how we evaluate others,” said Professor and Dr. Michael Graziano, a neuroscientist from Princeton University.

But what is personal space? Why have we evolved to need it? What are the levels of personal space that others must respect, and you as well?

The “Personal Bubbles” Created by the Brain

Our physical bodies have a clear boundary, distinguishing what is inside that belongs to us from what is outside, which we do not own. That boundary is your skin.

But just like a sovereign nation with airspace above its territory, our brains unconsciously create such buffer zones, extending the claim of ownership of space beyond our skin.

You don’t have to wait for someone to touch you to feel your sovereignty being invaded. Just the sensation of someone approaching, an object flying towards you, or even a gaze is enough. So where does this feeling of personal space come from?

In the book “The Spaces Between Us,” Professor Michael Graziano explains that there are two brain regions responsible for extending body sovereignty into external space. These are the parietal cortex, which processes sensory information, and the premotor cortex, which plays a role in every movement you make.

“These areas of the brain contain neurons that, once activated, will inform you whether something or someone is getting too close. If so, these two brain regions will direct you to react by squinting, shrugging your shoulders towards your ears, or moving away from the danger,” Professor Graziano writes.

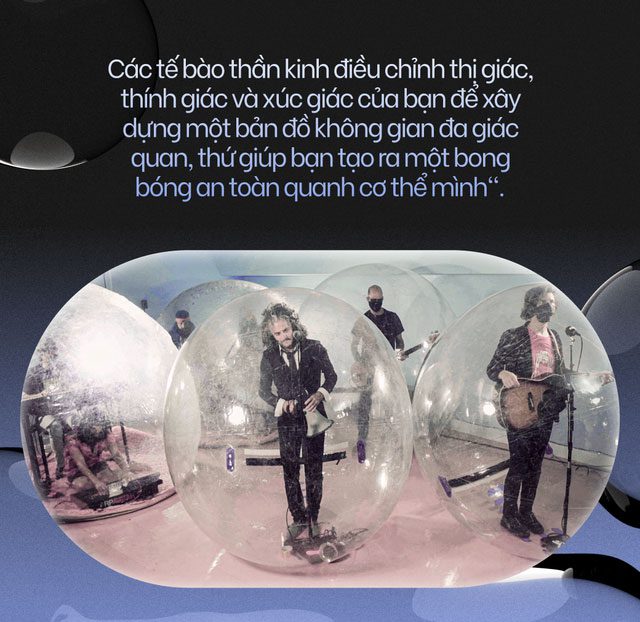

“I call them ‘bubble neurons.’ They adjust your vision, hearing, and touch to build a multi-sensory map of space that helps you create a safe bubble around your body.”

The brain then continues to process information about this bubble in two ways:

- It identifies external landmarks, such as the shape of the room or the position of chairs around a table.

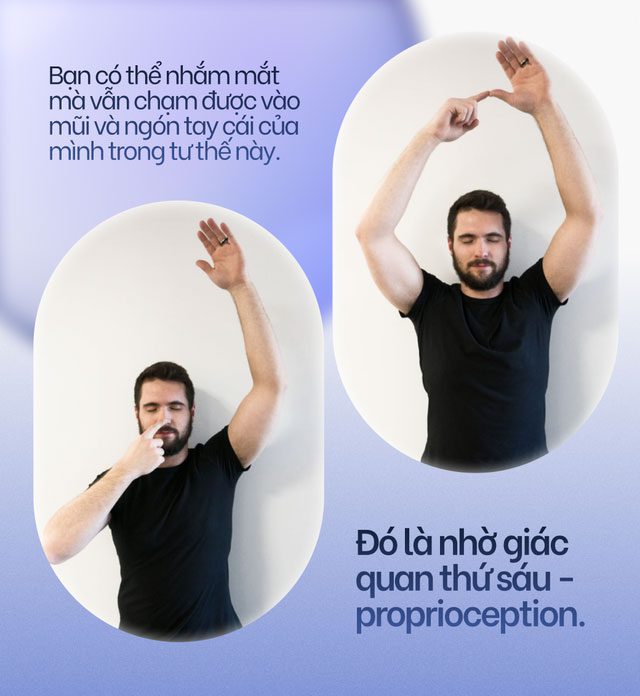

- It determines the location of objects or people within this safe bubble, using a sixth sense known as proprioception.

Proprioception is derived from the Latin word “proprius,” meaning “one’s own,” and “capion,” meaning “to seize.” Currently, there is no exact term in Vietnamese that can translate “proprioception.” However, I will explain this concept to you through an experiment:

First, place a cup of water in front of you. Next, touch the rim of the cup a few times with your eyes open. Now, close your eyes.

If I ask you to touch the rim of the cup with your eyes closed, you are likely to succeed. This is because when we close our eyes, the awareness of the world and our body’s position in space does not disappear.

An invisible sense remains that keeps track of where your hand is and where the cup is. This sense is called proprioception, allowing us to be aware of our body’s position in space.

Proprioception tells you where your coffee cup is on the table, allowing you to reach for it without looking. It helps you unconsciously gauge the position of chopsticks relative to your mouth while eating, so you don’t have to worry about the chopsticks poking your mouth. Without this sense, you would literally be “lost” in your own world.

However, what is particularly special about proprioception is that this sense can be activated even before vision and hearing. It helps you recognize when someone is approaching you, invading your safe bubble. It even informs you whether that person is a stranger or an acquaintance, before you see or hear them.

In summary, with the spatial planning abilities of the parietal cortex and premotor cortex, along with the predictions of proprioception, your brain creates a space that you control not only consciously but also subconsciously. As Professor Graziano explained, this is the space that you claim sovereignty over, being aware of what is intruding. This is your personal space.

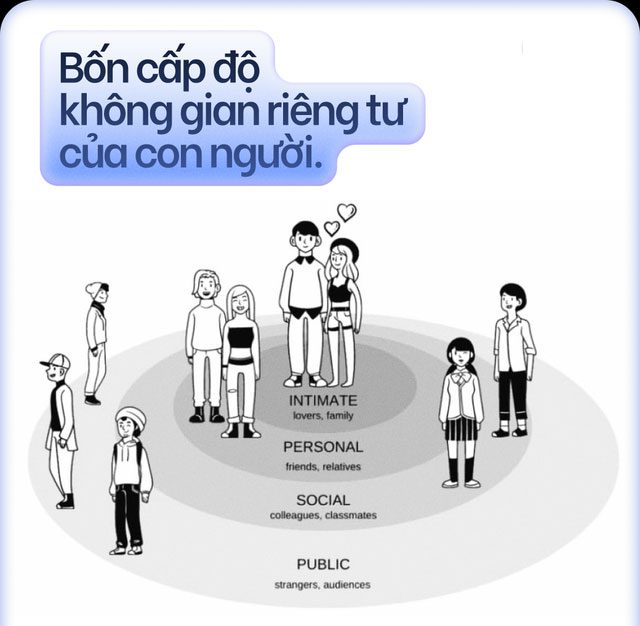

The Four Levels of Human Personal Space

Let’s take an example. Suppose you are standing at a party when a stranger approaches you. Although rationally you may tell yourself that a Homo Sapien, dressed in a black suit and tie in the 21st century, would not hide a large bone behind their back to hit you, subconsciously, your brain is still preparing for a scenario where that could happen.

We inherit this instinct from our ancestors, even those distant ancestors on the evolutionary branch alongside reptiles, birds, and mammals. This was confirmed in the 1950s by Swiss biologist Heini Hediger, who observed animals in his zoo in Zurich.

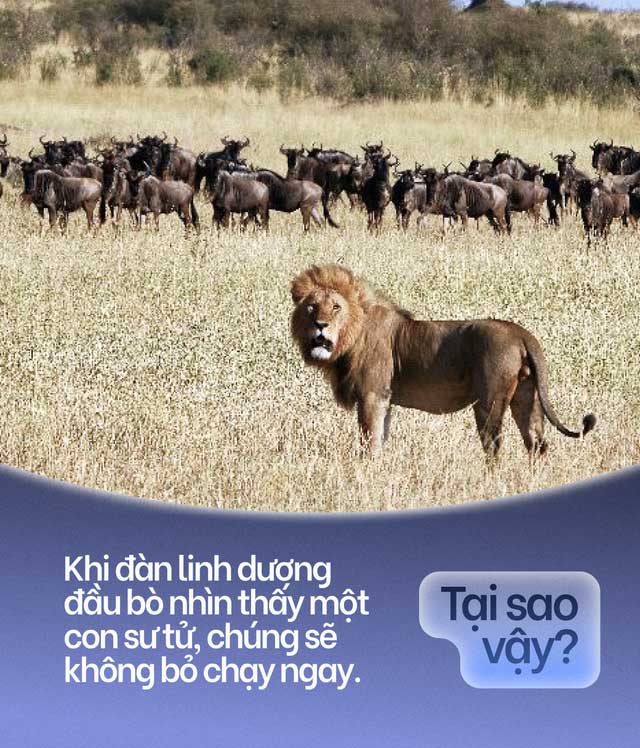

Hediger found that animals were only comfortable if their cages were spacious enough to create a buffer zone with the animal in the adjacent cage. This space was even established invisibly outside of their natural environment. For example, when a wildebeest sees a lion, it does not immediately run away.

Instead, the animal seems to perform a geometric estimation. The wildebeest remains calm until it realizes the lion is creeping into its space. Then, it jumps back a distance and regains space from the lion.

Hediger conducted experiments with many animal species to confirm their safe zones. Imagine him taking a measuring tape (or it could also be a basket of chewing gum) and approaching grazing wildebeests. When they jumped away, Hediger simply measured the distance he could approach. By summing these measurements and averaging them, Hediger would have a chart of numbers.

He discovered that larger animals have larger safe zones. For instance, a wall lizard has a safe zone of just a few meters before it recognizes a threat and runs away. But for a crocodile, this zone extends tenfold, up to 50 meters.

Domesticated animals, such as livestock, poultry, and pets, have smaller safety zones. Because they are so used to humans, the numbers Hediger measured in these cases often did not exceed 1 meter.

Heini Hediger’s work later attracted the attention of American psychologist Edward Hall. Hall argued that humans actually have the instinct to establish safe distances just like animals. The only difference is that we have domesticated each other to feel that a stranger poses less of a threat than a lion.

With the presence of laws, ethics, and mutual respect, we now allow a stranger to approach us, depending on the situation and circumstances. This distance can be shortened to a few meters down to several centimeters, similar to domesticated animals.

But how accurate are those numbers? Hall now wants to replicate Heini Hediger’s experiments to find out. He recruited pairs of volunteers who were family members, friends, or strangers to each other and asked them to move closer together until they felt uncomfortable.

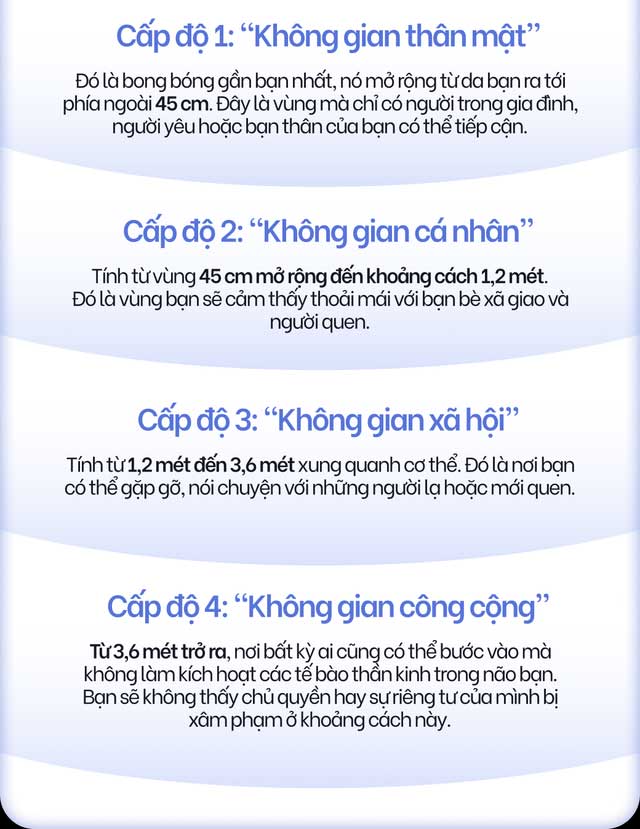

By repeating these experiments multiple times, Hall established 4 levels of personal space in humans. He described them in his book “The Hidden Dimension” in 1966. To this day, after numerous verifications and repeated experiments, the scientific community still agrees with Hall’s 4-level scale:

Of course, these distances are just averages. For each individual, it can vary based on gender, life experiences, culture, and personality. As Hall suggested, Arabs often have a smaller personal space at level 2. They may stand close together to talk. However, the British do not behave this way; they maintain a greater distance from strangers they do not know.

Studies show that introverts, those with psychological trauma, or anxiety tend to expand their safe zone. In contrast, extroverted, confident, and powerful individuals often exhibit behaviors that shrink their buffer without realizing that their actions may discomfort others.

The opposite is also true for women and men. For instance, women often tend to expand their personal space when a man approaches them. According to behavioral studies, women typically protect the space beside them, while men want to safeguard the space in front of them. This explains why you might want to sit next to her on a first date, but she may feel more comfortable if you both sit across from each other.

However, one thing holds true for almost everyone: emotions will influence our perception of these personal spaces. Essentially, when we feel anxious and stressed, we have a need to expand our safe space. When we are happy, especially with dopamine released in our brain, we tend to shrink our safe zone to allow others to enter.

“Think of these personal bubbles like a volume knob,” Professor Graziano says. “When your emotional volume goes up, your buffer expands further. When the volume goes down, it contracts.”

Protecting Your Personal Space While Respecting Others’ Space

Now that you have a basic understanding of personal space, you know you can control your behavior—not just by intuition, but also rationally.

For example, a girl who was willing to dance with you at a fun party the night before doesn’t mean she will be comfortable if you approach her at a distance of less than 45 cm the next day. Remember the dopamine effect that can shrink your safe space?

Similarly, never get too close to a stranger if you have a sense of respect for their personal space. In this way, elderly ladies selling chewing gum can effectively “up sell” simply by maintaining a distance of 1.2 meters from their potential customers.

But what if someone keeps invading your personal space intentionally? In some unavoidable situations, asserting ownership of your space is impossible. Here are some strategies you can use, according to psychology researchers:

Body Language: You can subtly use your instincts to alert someone that they are getting too close. A slight lean back, stepping back, or even running away can signal your discomfort. Some smarter strategies can even help you proactively prevent an invasion before it occurs.

For example, if someone wants to hug or kiss you on the cheek but you do not want your intimate space (level 1) to be violated, extend your hand to catch them, keeping them at your personal space (level 2).

If you think a neighbor or colleague tends to approach you too closely, try to stand and talk to them near a barrier, such as a mailbox or office chair, to maintain social space (level 3).

“Often, you can avoid unwanted touch or closeness just by saying ‘Step back!’ with your body language,” says Dr. Jane Adams, a psychologist and author of “Boundary Issues.”

Speak Up Politely: Suppose you feel uncomfortable when someone is unaware of personal spaces, and they do not even understand your body language. What then?

Dr. Tanya Menon, an organizational psychologist and professor at Ohio State University, suggests that the next step is to speak up politely. “You can say something like ‘I’m a germaphobe,'” Dr. Menon suggests if someone wants to hold your hand that you do not want.

Similarly, if you feel a supervisor is standing too close in an exam room making it hard for you to concentrate, sincerely state that you need space to think.

Sometimes You Have to Compromise: In some situations, invading your personal space is unintentional, non-sexual, and simply arises from cultural differences. For example, when meeting a foreign partner who greets everyone with hugs and cheek kisses, Dr. Menon advises that you should compromise.

In those cases, you might silently repeat a mantra to help yourself stay calm or simply remind yourself that the contact is harmless and just a short cultural interaction.

If the Invasion is Unavoidable: On a bus or in an elevator during peak hours, you may not be able to protect your intimate space of under 45 cm. Dr. Adams says there is a way to easily accept this issue: imagine you are in a bubble, which can help you feel calmer and safer.

Another tactic is to pretend that the people around you are just inanimate objects, like walls or trees, which can also alleviate anxiety about strangers getting too close.

When Should You React Forcefully? That’s when you notice your personal space is being invaded unreasonably. For example, when a colleague of the opposite gender intentionally massages your shoulders when you did not ask. Someone standing too close to you on a bus even when there are empty seats, or someone following you while keeping a distance of over 3.6 meters are confusing circumstances.

“If you are uncomfortable with someone’s touch or close proximity, you can absolutely ask them to step back,” Dr. Adams adds. React forcefully, even calling for help from others if you feel you are being clearly attacked in the space you have a right to own.