If you are familiar with the treasure trove of Vietnamese folklore, you are likely not unfamiliar with characters who specialize in humor to ridicule the ruling class. However, the tales of these characters are mostly fictional anecdotes, lacking in authenticity.

In contrast, European history has a “formal job” where one of the main roles is to humorously “poke fun” at kings and queens. This job is none other than that of a court jester. The court jester, or fool, is a real occupation in history.

The court jester is a real occupation in history.

However, the role of a jester is not simply to entertain the royal family. They also engaged in various other duties, such as advising, performing household tasks, or even accompanying their masters into battle. They were also the unfortunate individuals tasked with delivering bad news to the kings and queens.

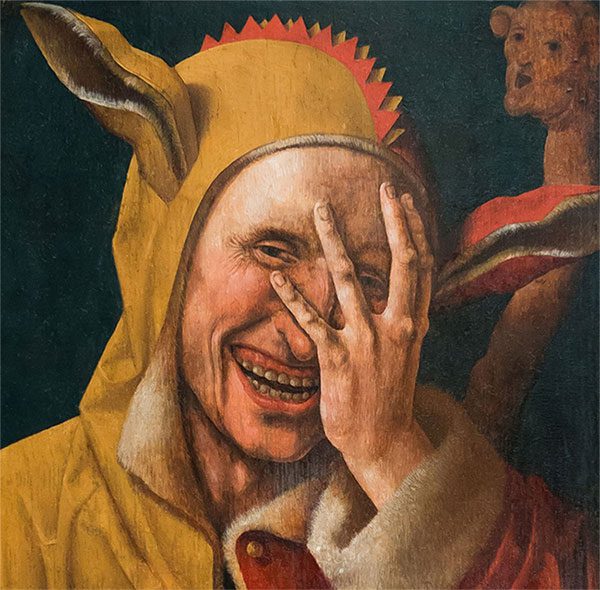

Most jesters were highly educated and very talented, capable of entertaining with jokes, juggling dangerous objects, or performing absurd artistic displays. Due to their close proximity to the royal family, they held significant political positions and often provided advice on various aspects of kingdom life.

Free to jest and provoke royalty

An important part of a jester’s career is finding ways to bring laughter to the palace. This could come from ridiculous performances or playful taunts that would make others feel “frustrated.”

In the 12th century in England, under King Henry II, there was a jester named Roland le Farterer, famous for his bizarre “talent”: producing music with flatulence. Every Christmas Eve, Roland would conclude his performance with “a jump, a whistle, and a fart” all at once.

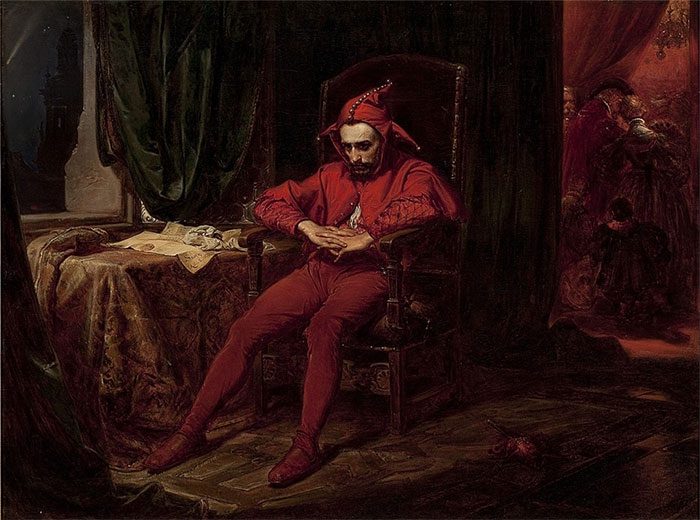

Jesters could publicly prank and mock kings and queens.

This “talent” itself, along with those who found it amusing, was quite peculiar, but it should not be underestimated. Thanks to this ability, Roland was awarded an estate in Suffolk along with 30 acres (about 12 hectares) of land.

Another privilege of jesters is that they could freely prank and mock kings and queens without the fear of severe consequences, unlike common subjects.

Crimes against the king did not exist in a jester’s vocabulary; on the contrary, they were encouraged. Of course, the “victims” were not limited to their masters but could also include other nobles if they felt inclined.

The reason they were often forgiven was that these jokes were rarely malicious; instead, they were typically meant to help their masters recognize their flaws or to bring harmless laughter to the banquet table.

A classic story involves King James VI, who ruled Scotland in the mid-16th century, and his jester George Buchanan. King James VI was exceedingly lazy, to the point of signing documents sent by officials without even reading them first. This became a serious issue in the kingdom.

To “address” this, George confronted James VI and tricked him into signing a document of abdication to hand over the throne to George for 15 days. From that point on, James VI never dared to overlook a line of documents presented for his signature again. If it had been any other courtier who dared to pull such a stunt, they would have certainly faced dire consequences.

Noble Privileges

Due to their closeness to powerful figures, court jesters enjoyed many privileges that commoners could only dream of. First and foremost was stable and decent housing within castles or estates. Notably, individuals like Roland mentioned above were even granted homes and land.

Another case is Archibald Armstrong, a royal jester in the 17th century. He was granted 1,000 acres (4 km²) in Ireland before being “retired” after going too far with his jokes.

Engraving of King Henry VIII, Queen Mary I, and jester William Sommers.

Additionally, court jesters were highly respected by the aristocracy, rather than being seen as mere servants. Contrary to popular belief, they did not don traditional jester costumes 24/7; instead, they dressed like nobles.

With their special role, they also enjoyed greater rights than commoners, even over officials and lords, particularly freedom of speech. They were allowed to express their opinions on various issues, gaining the trust of their masters with sincere remarks about decisions and actions within the kingdom, from which they could offer advice.

Another unique aspect is that the recruitment process for this job was not based on status or background. They could be an excommunicated clergyman or mere servants and slaves. Jesters often had unattractive appearances alongside sharp and clever minds.

Although intelligence was a common trait, many courts preferred jesters with physical or mental disabilities. They were referred to as “fools” and were only provided food and shelter without any privileges.

The Most Dangerous Job of the Medieval Era

Not only did they serve within the palace walls, but sometimes court jesters also participated in battles alongside their masters due to their close relationships. Occasionally, they even advised their superiors.

They even took part directly in psychological warfare, boosting the morale of their own troops while demoralizing the enemy. When formations were set, these special “soldiers” would stand in front of the ranks, hurling insults and taunts at the opposing side. This not only elevated the fighting spirit of their soldiers but also caused hasty enemies to break formation and charge recklessly to their demise.

The night before battles, they would also entertain and perform various acts, such as singing, storytelling, or juggling, to help soldiers relax and enter the battlefield with the best spirits.

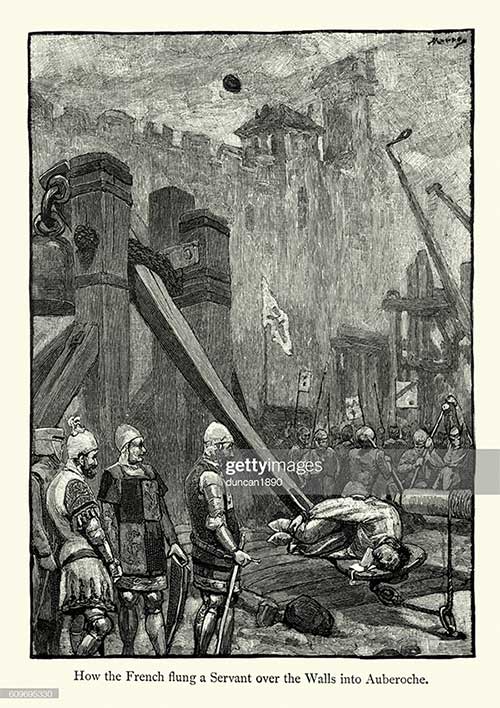

However, they did not only face arrows and spears; they also carried two extremely heavy responsibilities: that of a messenger and a newsbearer.

Court jesters were often very talented.

As messengers, their role was, of course, to deliver letters and demands from their masters to the opposing side. If the messages became too unpleasant, the unfortunate messenger would bear the brunt of the enemy’s wrath. A common fate for messengers was to be catapulted back to their starting point, sometimes whole or, in some cases, just their heads.

Unfortunate medieval messengers could be “flown” by catapult.

The second task was also crucial, albeit slightly less dangerous. Feudal lords were notoriously hot-tempered and had a habit of venting their anger on the bearer of bad news from the battlefield. In such cases, other courtiers would pass this heavy burden onto the jester.

To preserve their lives and ease their masters’ tensions, they would have to conjure up a joke from the grim news.

History recounts that in 1340, the entire French naval fleet was destroyed by the English at the Battle of Sluys. No one dared to report this to King Philippe VI except his jester. Upon meeting his master, the jester said: “The English sailors don’t even have the guts to jump into the water like our brave French soldiers!”.