Underestimated due to their gender and background, these women have proven to be indispensable pieces in humanity’s quest to conquer the Moon.

Exceptional Minds in Calculation but Undervalued

In 1965, Poppy Northcutt was the only female engineer at NASA’s Mission Control in Houston. Working in a major space agency, Northcutt was always confident in her intellect, but navigating an environment deemed a “man’s domain” was not easy.

As a result, Northcutt sometimes felt isolated in her workplace. Like thousands of other women working at NASA, she was responsible for calculating data. This task arose before the advent of electronic computers, and these women would use their mathematical talents to perform all necessary calculations for experiments.

Historically, women had held this position long before, as evidenced by groups of “computers” working at Harvard Observatory and Greenwich Observatory in the late 1800s. At NASA, these women would handle the most critical calculations to send astronauts to the Moon.

Not feeling as isolated as Northcutt, Sue Finley had many female colleagues working alongside her at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena, California. Not only were the supervisors female, but nearly all members of the computing team were women.

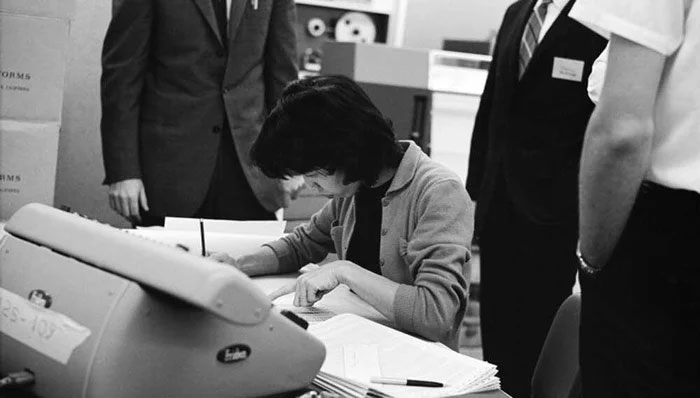

The computing staff at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

On the evening of January 31, 1958, when female observer Barbara Paulson announced that America’s first satellite, Explorer 1, had left the atmosphere and entered space, the entire room erupted in joy. This marked the moment when the United States had caught up with the Soviet Union in launching a satellite into space, and it was also the moment when the Moon became their next target for conquest.

Following this success, Finley began adjusting designs and trajectories to realize the goal of sending robots to the Moon. Her team focused on the Ranger project (1961-1965), aimed at sending cameras to the Moon to capture close-up images of its surface and select a safe landing site for Apollo.

Next came the Surveyor project (1966-1968), primarily tasked with gathering additional data on temperature and surface composition. Additionally, Finley was involved in the design of large radio antennas responsible for tracking and communicating with Apollo.

Talent Suppressed by Racial Discrimination

All the women working at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the 1960s were highly trained mathematicians, many of whom held advanced degrees.

Helen Ling in the laboratory.

Helen Ling, born in China and having experienced a tumultuous childhood during World War II, held a master’s degree in mathematics and managed the computing division at the laboratory for over three decades.

Janez Lawson, the first African American female engineer at the laboratory, held a bachelor’s degree in chemical engineering from the University of California, Los Angeles. With such qualifications in modern times, she would have been honored to become an engineer, but the racial discrimination of the 1950s prevented that, and she could only secure a minor computing position.

Moreover, the “human computers” who were African American women were segregated from NASA’s main work center and assigned to a group called “Western Area Computers.” This discrimination not only meant they were paid significantly less than their white counterparts but also that their working, dining, and restroom facilities were separate.

However, these racial discriminations could not diminish their importance. Author Margot Lee Shetterly wrote the book Hidden Figures (2016), telling the true story of three women who worked at NASA, which was later adapted into a famous film of the same name.

The three women mentioned in the book relied on their own talents to rise from computing staff to become legitimate engineers: Katherine Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, and Mary Jackson. Whenever the first human spaceflight is discussed, it is impossible not to mention these three talented women.

Katherine Johnson.

John Glenn, one of the first astronauts, once stated about Katherine Johnson, “If she says that the numbers are good, I am ready to go to the Moon.” Not only did Johnson calculate the numbers, but she also designed the trajectory for his 1962 Earth orbit flight.

The Indispensable Role of Women in Moon Exploration

To execute a lunar flight, NASA required multi-stage rockets, with the lower part providing thrust. Upon reaching a certain altitude, this section would automatically detach and fall back to Earth while the upper part of the rocket would head straight for the Moon. This operation was conducted at NASA’s laboratory in Ohio, led by Annie Easley, an African American woman with a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Cleveland State University.

Annie Easley at the research center in Cleveland.

Like other women working there, Easley began with computing tasks. However, by the mid-1960s, with the emergence of electronic computers that were faster and more flexible than manual calculations, employees like Easley had to shift to programming for the space agency.

This was also when Easley began programming the engines for the Centaur rocket, technology that would soon become a crucial part of Apollo.

Meanwhile, at the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the components of Apollo 11 were being assembled. Under the calculations of many female engineers across the country, the rocket was gradually being completed. Among the engineers was JoAnn Morgan, a young 28-year-old who specialized in operating measuring devices and had worked at the center since NASA’s establishment in 1958.

Similar to Northcutt, Morgan was the only woman working in the control room at Kennedy. Although she had participated in all previous Apollo launches, this 11th launch would mark her first time sitting at the control desk.

However, it seemed that journalists at the time were not pleased with a woman sitting in the control room, in such an important position as Morgan’s. One reporter even approached her and said to a male colleague nearby, “I hope you can let her out and put on some lipstick.”

JoAnn Morgan at the Kennedy Space Center.

Yet, lipstick was not what Morgan would think about on the morning of July 16, 1969, when Apollo 11 was officially launched into space.

Four days later, on July 20, Apollo began its descent to the Moon’s surface. But just three minutes before landing, the computer system issued a warning about an emergency, forcing engineers to make a decision: to press on despite the risks or abort the mission.

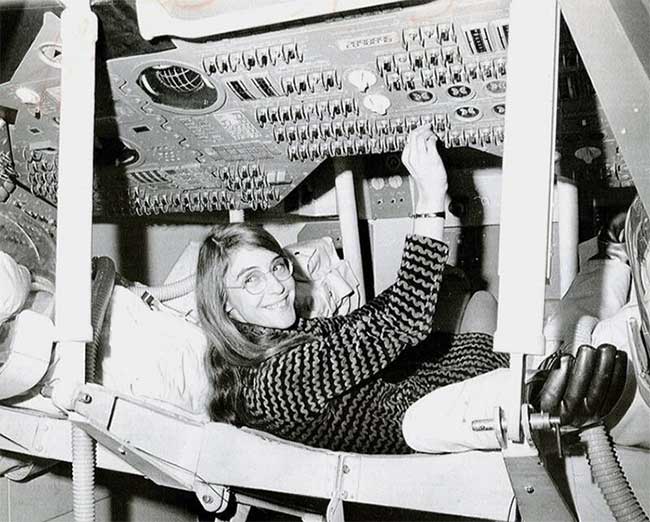

Fortunately, female engineer Margaret Hamilton had long prepared for this scenario. Thanks to the error detection and correction program she wrote, the software rebooted, and Apollo 11 landed successfully.

Margaret Hamilton.

The moment astronaut Neil Armstrong stepped down from the spacecraft before the eyes of all humanity, taking the first step on the Moon’s surface, became an iconic moment: “That’s one small step for man, one giant leap for mankind.” However, that moment was not solely created by men; it was the result of thousands of people, both men and women, from various races and nationalities, all striving to achieve one of humanity’s greatest accomplishments.

For the women working in the aerospace industry, their work was just the beginning. In the future, not only the Moon but also other planets in the Solar System will continue to be explored. For them, new missions are still ahead.