Dr. Thomas Hodgkin was the first to discover and describe Hodgkin’s disease, but received indifference from the research community.

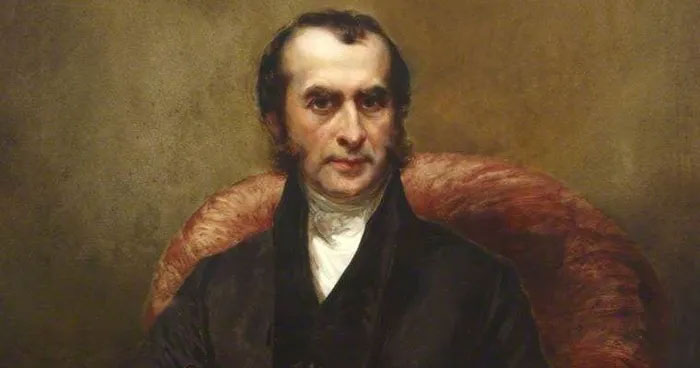

Hodgkin’s lymphoma emerged relatively late in the world of cancer. The discoverer of this disease, Thomas Hodgkin, was a thin, tall English anatomist in the 19th century, sporting a remarkable handlebar mustache and an astonishingly curved nose—a character who might have stepped out of an Edward Lear poem.

Born in 1798 into a Quaker family in Pentonville, a small village on the outskirts of London, Hodgkin was a precocious child who quickly grew into a knowledgeable young man with interests ranging from geology to mathematics and chemistry. He briefly apprenticed as a geologist, then as a pharmaceutical chemist, and eventually graduated from the University of Edinburgh with a medical degree.

Portrait of Dr. Thomas Hodgkin. (Photo: Findagrave).

An incidental event tempted Hodgkin into the world of pathology and led him to the disease that would bear his name. In 1825, a struggle occurred among the faculty of St. Thomas’ Hospital and Guy’s Hospital in London, splitting this esteemed institution into two opposing factions: Guy’s Hospital and its new rival, St. Thomas. This division, much like many marital disputes, was almost immediately followed by a heated debate over the division of assets.

The “assets” in question were a terrible collection—a valuable anatomical collection of the hospital: brains, hearts, stomachs, and skeletons preserved in formalin, stored as teaching tools for the hospital’s medical students. St. Thomas’ Hospital refused to share these precious specimens, prompting Guy’s Hospital to struggle for its own anatomical museum.

Hodgkin had just returned from his second visit to Paris, where he had learned to prepare and analyze cadaver specimens. He was quickly recruited to collect specimens for the new museum at Guy’s Hospital. The most creative academic privilege of this work was perhaps his new title: curator of the museum and expert in the morgue.

Hodgkin proved to be an extraordinary expert in the morgue, an indispensable anatomical curator who amassed hundreds of specimens within a few years. While collecting specimens was a rather monotonous task, Hodgkin’s special talent lay in organizing them. He became a librarian alongside a pathologist; he invented his own pathological classification system.

His method of organizing pathological specimens by organ system rather than by date or type of disease was a breakthrough. By doing so, “residing” conceptually within the body, climbing in and out at will, he frequently noted correlations between organs and systems—Hodgkin found that he could instinctively recognize patterns in patterns, sometimes without even intending to record them.

In early winter of 1832, Hodgkin announced that he had collected a series of cadavers, primarily of young men, who exhibited a strange systemic disease. The hallmark of the disease, as he described, was “an unusual enlargement of the lymph nodes.” To the average eye, this enlargement could easily be attributed to tuberculosis or syphilis—more common sources of lymphadenopathy at the time.

However, Hodgkin was convinced that he was encountering a completely new disease, an obscure pathology characteristic of young men. He wrote about the cases of those seven cadavers and presented a report to the Medical and Pathological Society: “Some manifestations of disease in the lymph nodes and spleen.”

The story of a young doctor […] did not receive much sympathy. It is said that only eight members of the society attended this report. They left in silence, not even bothering to sign the dusty attendance sheet.

Hodgkin was also somewhat embarrassed by his discovery. “A pathological article would likely be considered of little value unless accompanied by suggestions designed to support treatment, such as cures or pain relief,” he wrote.

Merely describing a disease without offering any therapeutic suggestions seemed to him a hollow academic exercise, a form of intellectual waste. Shortly after publishing his research, he began to drift away from medicine entirely.

In 1837, after a rather heated political dispute with his superiors, he resigned from Guy’s Hospital. He had a brief stint at St. Thomas’ Hospital as a museum curator—a failed return. By 1844, he completely abandoned academic pursuits. His anatomical research gradually ceased.

In 1898, thirty years after Hodgkin’s death, an Austrian pathologist, Carl Sternberg, observed through a microscope the lymph nodes of a patient and found special cell clusters: giant, disorganized dividing cells, with bilobed nuclei—“owl-eye cells,” as he described them, with a mournful gaze emanating from the lymphatic forests.

Hodgkin’s anatomical research had reached the cellular level. The owl-eye cells are malignant lymphocytes, lymphocytes that have turned cancerous. Hodgkin’s disease is a form of lymphoma.

Hodgkin might have been disappointed by what he thought was merely a descriptive study of this disease. However, he underestimated the value of careful observation—by forcing himself to study anatomy, he inadvertently made the most significant discovery regarding this type of lymphoma.