According to reports to date, approximately 56 individuals with Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) have been identified worldwide.

In recent years, the phenomenon of Highly Superior Autobiographical Memory (HSAM) has gained attention among the scientific community following the emergence of the case of AJ in 2005.

A study published in 2013 by psychologist Dr. Lawrence Patihis and his research team at the University of California stated: “Individuals with HSAM can remember what day of the week a specific date fell on and provide details about events that occurred on that day, and this applies to every day of their lives since early childhood. For verifiable details, those with HSAM have an accuracy rate of up to 97%.”

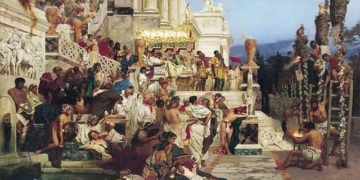

Individuals with HSAM have an accuracy rate of up to 97%. (Image source: Leonardo).

After researching AJ’s case, over 200 individuals claiming to have similar abilities contacted McGaugh’s team. The scientific community felt intrigued, as this ability might be more common than they had previously imagined. The surge of individuals volunteering for experiments signaled the potential for groundbreaking studies on memory.

However, as with many previous cases, one after another, individuals did not meet the criteria for true HSAM. While those who reached out had good memories, none stood out like AJ.

Just when researchers were about to lose hope, a miracle occurred. Another individual with HSAM emerged: Brad Williams. Then came another: Rick Baron. Next was Bob Petrella.

By 2010, the team even welcomed a famous member, actress Marilu Henner.

According to reports to date, there are still approximately 56 individuals with HSAM identified worldwide.

This remains a small group, but it is significantly more meaningful and useful than just a single case. Naturally, the question that arises in people’s minds upon seeing such an extraordinary group is “How is this possible?”

While it is still too early to provide a compelling and well-founded scientific explanation, there are some hypotheses to consider.

Perhaps memory functions like a recording device, capturing everything we do. And individuals with HSAM may be better at utilizing the playback feature than the rest of us.

A landmark work released in 1952 titled Memory Mechanisms, written by renowned American neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield, suggests there is some evidence supporting this notion. One of the research topics Penfield was most interested in was treating epilepsy patients by severing certain parts of the brain.

While performing surgery, he used an electrical probe to stimulate areas of the brain and asked patients (who were still awake) to recount their experiences. His technique clearly outlined sensory and motor cortex regions, and to this day, we still use that cortical map.

He found that when stimulating certain parts of the brain, particularly the temporal lobe, patients reported experiencing complex hallucinations (the temporal lobe is a large component of the brain located behind the ears on both sides). When electrical currents were transmitted across the left and right hemispheres in the area of the temporal lobe, patients stated they heard voices of loved ones or even heard singing. It seemed this region directly stimulated auditory memories.

Like many researchers of his time, he suspected the hippocampus played a mediating role, allowing or preventing us from accessing certain memories from the stream of consciousness. Thus, he referred to the hippocampus as the “access key” and discussed it in correspondence with Brenda Milner in December 1973. He claimed to have conceived this idea while studying a patient who had lost their memory after surgery.

If Penfield is correct, everything we remember is stored somewhere in the brain, which could explain the abilities of HSAM individuals as they may access this information more easily.