Once a mysteriously vanished civilization, the Trypillians were less focused on technical progress and more inclined towards spiritual awareness.

The land of Ukraine still holds secrets and mysteries about one of humanity’s most enigmatic civilizations that emerged here around 7,000 years ago and lasted nearly three millennia.

Ancient Civilization

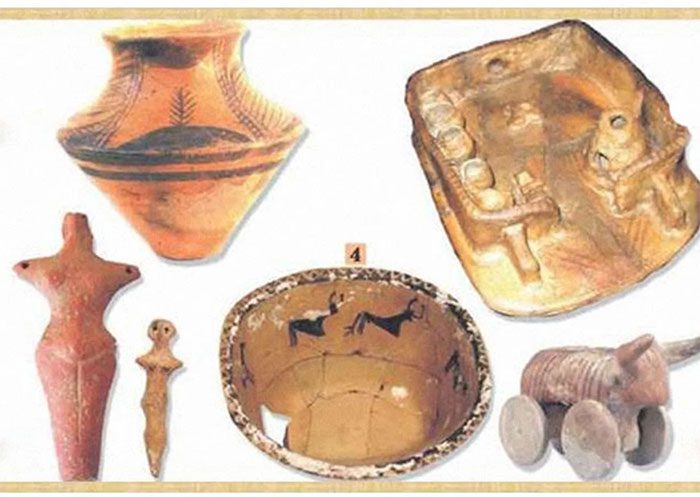

Artifacts of Trypillia culture. (Photo: kyivpost.com).

Scientists identify this as a branch of ancient European civilization that emerged after the Great Flood. Traces of this Bronze Age civilization were first discovered over 200 years ago near the small town of Trypillia, located 40 km south of Kiev, thus it was named “Trypillia Civilization.”

This civilization flourished from 5,500 to 2,750 BC over a vast area of 350,000 km2 stretching from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dnipro River. Most of this area is now Ukraine, with the remainder including Romania and Moldova. In different periods, estimates of the population of this civilization ranged from 400,000 to 2 million people.

The first person to discover traces of this ancient civilization was Vincenc Častoslav Chvojka, a Czech agronomist. In 1896, Chvojka purchased a plot of land in Trypillia, then a small village, for farming. During land cultivation, decorated pottery, bronze tools, gold jewelry, small statues, and other artifacts discovered by local hired farmers at a depth of nearly 1 meter caused a global sensation. In the decades that followed, archaeologists uncovered countless artifacts proving that this was a highly developed ancient civilization.

Houses, temples, figures of humans and animals, pottery, carts, sleds, chairs, and thrones were all made of clay. The Trypillians were skilled artisans. They had a profound understanding of materials and their properties, and could manipulate their uses so skillfully that modern potters can learn much from them.

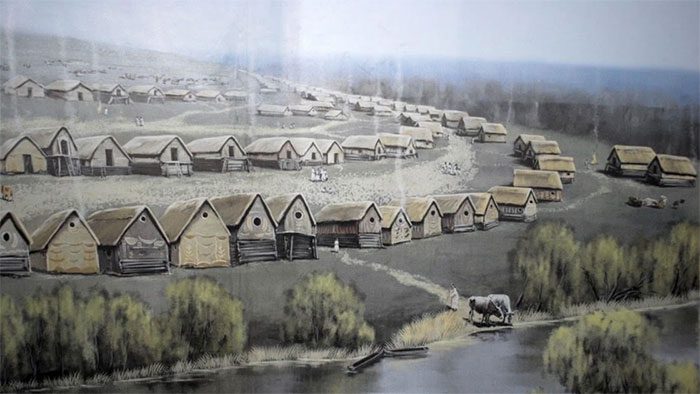

Model of Trypillia settlement. (Photo: kyivpost.com).

The Trypillians constructed their settlements in concentric circles, with some of these settlements housing populations exceeding 15,000 people—a colossal figure even for the Middle Ages. One of the largest known Trypillian cities was discovered in the village of Talyanki, Cherkasy region, Central Ukraine, covering an area of 450 hectares and a population of 30,000 people.

The Trypillians lived in unusual two-story houses, with the ground floor designated for household items and livestock, while the upper floor was for humans. The windows were round, the front door thresholds were high, and they never locked their doors. They painted the walls of their houses (both inside and out) along with their household items, agricultural tools, dinnerware, and small statues. They developed their unique style of painting animals and humans.

Trypillian women ground flour using heavy stone grinders, taking half an hour to produce nearly half a pound of flour from black barley, a technique that had not changed for thousands of years. Their lives were rich with sacred values and various rituals, where everything held special significance. Clothing, homes, social activities, and even everyday items were considered sacred. For instance, jars and pots were believed to protect everything they contained—from water to the ashes of the deceased, whom they cremated rather than buried.

Two-story house of Trypillians. (Photo: kyivpost.com).

Traditions and Symbols

The signs and symbols painted on the Trypillian pottery were not merely ritualistic images. They are prototypes of symbols—a form of primitive impressionism—and even a “germ” of written language. These signs represented a step forward, later evolving into writing and are indeed one of the very few sources of information about the Trypillia civilization that have survived through millennia of history. This civilization left no pyramids, stone churches, or stone monuments, only painted pottery.

The decorations of the Trypillians bore symbols that appeared millennia later in various parts of the world and became defining emblems in major religions: Yin-Yang, the Cross, and the Crucifix all originated from Trypillia culture. But the fundamental symbol is the universal, infinite spiral.

And like all women throughout the ages, Trypillian women loved jewelry, not only as trinkets and brightly colored adornments but also as amulets made from clay, shells, copper, and gold. They wore embroidered dresses and wove decorative patterns. Their clothing not only provided warmth but also carried protective significance against evil spirits and witches.

One of the countless artifacts discovered by archaeologists in excavations is a statue of a woman seated on a throne shaped like a bull’s head. In this culture, the bull symbolizes the male and the cow symbolizes the female as the beginning of “Mother Nature”, life, and all things (the cow is a sacred animal and a symbol of fertility).

The Trypillians also raised pigs, sheep, and poultry, and most scientists believe they were the first on Earth to domesticate horses. In addition to the comprehensible ceramic artifacts, there were other items whose purpose and meaning can only be guessed. For example, one of these is called “Trypillia Bincular”—a strange object resembling two vases fused together.

Trypillia Bincular. (Photo: kyivpost.com).

It remains unclear what the “Trypillia Bincular” was used for. Perhaps it was a drum, a vase, or a symbol of marital fidelity. Or it could have been used to catch rainwater. Such artifacts have not been found in any other civilization, while similar objects abound in Trypillia.

The Trypillians were very skilled farmers, yet they never improved their extensive farming methods. After the fields became depleted after six or seven decades, they would burn down their homes and move elsewhere to build new ones. Fire was very sacred to them. They believed that everything and everyone—land, homes, animals, and people—had to undergo a cleansing process through fire. That is why they burned their hometown cities after each generation.

Mysterious Cave

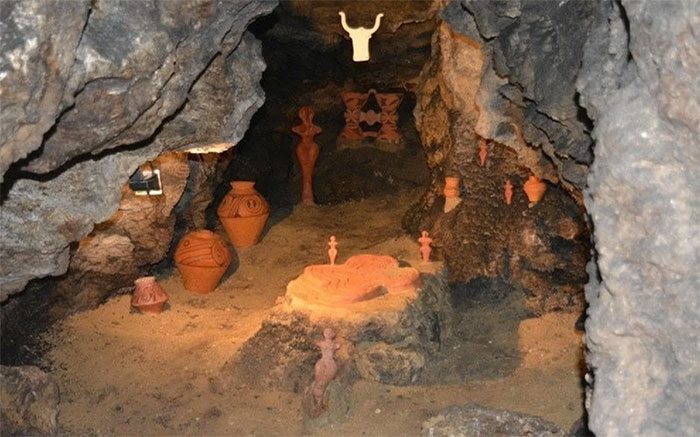

In 1828, farmers in the village of Bilche-Zolote in the Ternopil region of Central-West Ukraine accidentally discovered a cave that later became a pilgrimage site for archaeologists and tourists from all over the world.

Polish Prince Leon Ludwik Sapieha, the owner of the village at the time, amassed a large collection of thousands of Trypillia artifacts he found in the cave and restored them. He even had to use his large wine cellars to store them. Later, many of these artifacts were transferred to museums in Krakow, Vienna, and other cities in Europe.

The locals referred to the cave as Verteba, which in their dialect means “gutter” or “mountain cleft.” Hidden in the bushes, the entrance is quite hard to find. Remarkably, this place had remained unknown for thousands of years.

Verteba Cave is essentially a series of enormous underground corridors/tunnels supported by hundreds of columns and connected by maze-like passages. Scientists continue to debate its purpose. Some believe it was a type of sacred historical structure, akin to Stonehenge in England.

Others think it was a refuge for the Trypillians during the final centuries of their existence. As warring tribes from the North began to invade the fertile lands to the West along the Dnipro River, the Trypillians sought refuge in the underground cave where the temperature never exceeded +9° C. This raises the question of how so many generations of those people managed to live in Verteba Cave for decades.

Trypillia exhibition in Verteba cave museum. (Photo: kyivpost.com).

The Verteba Cave was not only a refuge for the Trypillians, like during World War II when Jews hid there to escape the Nazis and after the war.

There are thousands of artifacts that can be found in caves. Archaeologists have left some of them as they are, merely cleaning the surrounding space.

The Verteba Cave holds many secrets. For instance, how could humans have obtained light when they lacked lamps? The clues may lie in the numerous traces of hearths and soot marks on the walls. Some archaeologists suggest that if the Trypillia people lit fires spaced about 10 meters apart, they could have had light without any torches or lamps.

Today, we often wonder why the Trypillia people never seemed to care about technological advancement while forgetting the spiritual heights they achieved. Before their civilization ceased to exist, they had developed unique and highly sophisticated painting skills. Perhaps they found the meaning of their lives in the unchanging continuity, in the pursuit of immortality. Their art, culture, and way of life appear to have been millennia ahead of their time—a future that today’s human civilization is striving towards.