56 million years ago, a global warming event led to ocean acidification and the extinction of many marine organisms, significantly impacting the Gulf of Mexico—a region where life was once “protected” by the unique geology of the basin—according to research from the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG).

Published in the journal Marine and Petroleum Geology, this discovery not only sheds light on the mass extinction of ancient organisms but may also help scientists understand how current climate change will affect marine life and assist in the search for oil and gas reserves.

Marine organisms could not survive in many other areas, but the Gulf of Mexico remained unaffected.

“Although the Gulf of Mexico has changed significantly today, valuable lessons can be learned as we in modern times understand how climate change has impacted this gulf in the past,” said UTIG geochemist Bob Cunningham, the lead researcher.

Cunningham and his team investigated ancient global warming phenomena and their effects on marine organisms, as well as the chemical impacts, by studying sediments, mud, sand, and limestone found throughout the Gulf region.

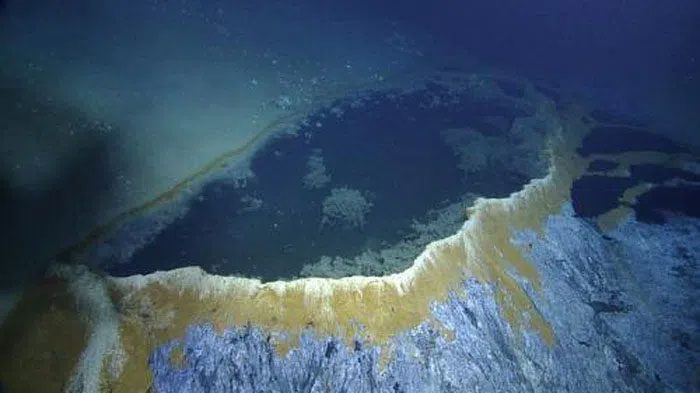

The researchers screened rock fragments brought up during oil drilling and discovered numerous bacteria from plankton species that thrived in the Gulf during the ancient warming period. They concluded that a stable supply of river sediments and oceanic circulation helped radioactive organisms and other microorganisms survive even when Earth’s warming climate threatened life.

“Marine organisms could not survive in many other areas, but the Gulf of Mexico seems to have been unaffected like other oceans,” said biologist Marcie Purkey Phillips of UTIG.

About 20 million years before the Earth warmed, the uplift of the Rocky Mountains redirected rivers into the northwest Gulf of Mexico—a tectonic change known as the Laramide Orogeny—leading most of the continent’s rivers through Texas and Louisiana into deeper waters of the Gulf. As global warming occurred, North America became increasingly hotter, and rain-fed rivers would draw nutrients and sediments into the basin, providing ample nourishment for plankton and other food sources for predators.

Studies also confirm that the Gulf of Mexico remains connected to the Atlantic Ocean, and the salinity of the seawater in this area has not reached extreme levels. According to Phillips, the presence of radioactive organisms alone confirmed that the Gulf’s waters did not become overly saline. Cunningham added that the organic content of sediments decreases as you move away from the shore—a sign that deep currents driven by the Atlantic are sweeping the basin’s floor.

These findings are crucial for researchers investigating the impacts of today’s global warming as they illustrate how the water and ecosystem of the Gulf have changed during periods of climate change.

For John Snedden, a co-author of the study, this is a perfect example of how industry data is used to address significant scientific questions.

“The Gulf of Mexico is a massive natural archive of geological history that has also been closely examined. We have used these databases to investigate one of the highest thermal events in the geological record, and I think it gives us an overview of a very important time in Earth’s history,” he stated.