Filled with intricate sketches and detailed notes, Leonardo’s notebooks reveal his passion and forward-thinking mindset that was centuries ahead of his time.

Video: Newsthink

Leonardo da Vinci is perhaps best remembered as a painter, with the Mona Lisa and the mural “The Last Supper” being among the most famous masterpieces in the world. However, in terms of quantity, painting may be the least prominent of his contributions to the world. Leonardo has only 22 paintings displayed around the globe and a few hundred other personal sketches. Instead, the genius lived during the glorious Renaissance period in Italy in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, excelling in various fields from architecture to science, mathematics, and engineering.

His notebooks are filled with scientific observations, reasoning, and hypotheses, many of which would be validated by independent researchers centuries later. He sketched designs for countless types of engines and machines, many of which have become a reality in the world. Some of the notebooks of the Italian genius showcase a vision, observational skills, and discoveries that transcend time.

Mathematics

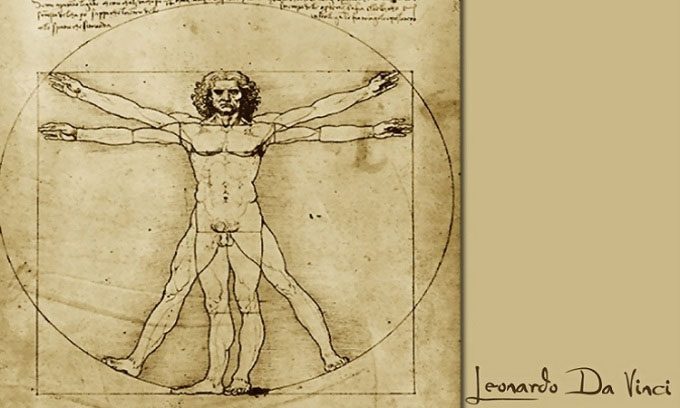

Obsessed with geometry, Leonardo conducted numerous measurements in nature, seeking relationships and patterns, which he then expressed through mathematics. He was particularly interested in the proportions of the human body. Based on the work of the Roman architect Vitruvius, Leonardo’s ink drawing “Vitruvian Man” from 1487 depicts a man in two overlapping positions with arms and legs extended within a circle and square, exploring the geometry of perfect proportions.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man. Photo: WordPress

Leonardo summarized the corresponding proportions of each body part with other parts in the notes below the drawing. The drawing also reflects his belief that humans are a miniature representation of the entire universe. Leonardo was also interested in the golden ratio, a mathematical ratio that creates aesthetic harmony. Defined by the length in relation to the width and equal to 1/1.618 (1.618 is known as Phi), this is “the divine proportion.” For example, in his unfinished painting “Saint Jerome,” the shape of the priest is accurately depicted according to the golden ratio. Leonardo also applied the golden ratio when painting portraits of young women, including the “Mona Lisa.”

Leonardo also enjoyed drawing ugly people. He was fascinated by contrast, placing the ugly next to the beautiful to highlight the latter. He always carried a sketchbook to draw many faces in crowds. In the late 1480s to early 1490s, Leonardo created numerous ugly, bizarre, and unusual sketches of men, women, and animals. Some images caricatured local people, while others were humorous. This is evidence of Leonardo’s keen observational skills and understanding of psychology.

Architecture

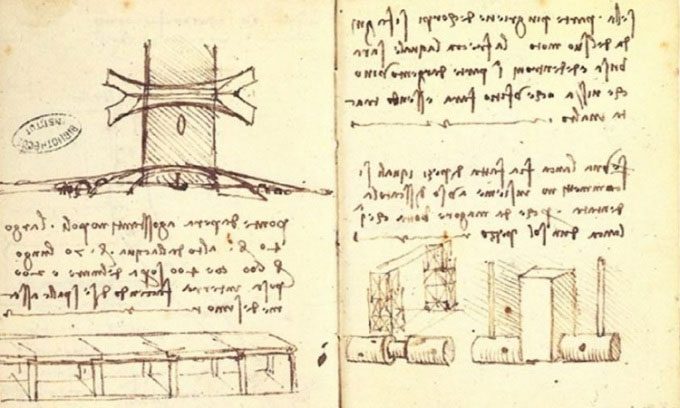

Drawings and plans for buildings filled Leonardo’s notebooks. He was drawn to architectural aesthetics as well as acoustics in churches. He was determined to discover ways to combine structures that would allow a priest’s voice to reach the farthest corners of a church. Leonardo conceived the teatro da predicare, a preaching hall with a circular theater shape. He was officially appointed as architect, painter, and engineer for King Francis I of France in 1515. Leonardo designed military fortifications to accommodate increased artillery use, creating sloped walls with a wider base to prevent the walls from weakening due to continuous bombardment.

The design of a bridge by Leonardo da Vinci for Sultan Bayezid II. (Photo: TRT)

In 1502, Sultan Bayezid II of the Ottoman Empire commissioned Leonardo to design a bridge, and Leonardo submitted the drawings. The bridge would have a span of nearly 275 meters, crossing the Golden Horn in Istanbul with an arch high enough for ships to pass underneath. Considering Leonardo’s bridge technically unfeasible, Sultan Bayezid II did not choose the design, but modern architects proved the king’s decision wrong by using Leonardo’s design to build a bridge over a highway in Norway in 2001.

Nature

In the early 1490s, Leonardo traveled north twice to the Alps in Italy. There, he quickly recorded observations and sketched. He carefully described and documented flora and fauna, especially birds. These trips led to the creation of several notable storm drawings, accurately illustrating the direction and strength of a downward airflow called downburst.

Leonardo also examined fossils and soil formations. He made some of the earliest modern scientific conjectures about geology and natural history. His cliff sketches clearly show strata from various geological periods. Most notably, he speculated that the Earth was much older than the prevailing views of his time.

Leonardo’s interest in nature gradually shifted to careful study and observation by the late 15th century when he lived in Milan. He set aside a notebook dedicated to optics or the behavior of light. The entire notebook was presented very neatly and meticulously, with detailed drawings that integrated his knowledge of geometry, comparable to modern experimental books.

Inventions

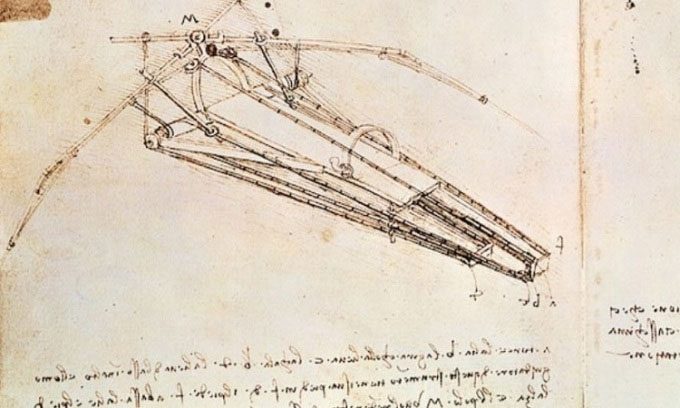

Design of a bird-like flying machine by Leonardo da Vinci. (Photo: National Geographic)

Many modern inventions were inspired by Leonardo’s ideas, including parachutes, mirror grinding machines, scissors, drawbridges, mitre locks (used in canals), and spring-driven mechanisms (mainly used in toys). He may be most recognized in the field of flight, long before the first airplane became a reality. The Italian genius created over 500 sketches of flying machines and wrote more than 35,000 words of description.

Anatomy

Leonardo documented his studies on human anatomy through drawings and accompanying notes, revealing details that had never been described before, including two particularly notable cases. The first was an elderly man suffering from arteriosclerosis and arterial blockage. This was a heart disease diagnosis made centuries before doctors recognized the symptoms. Around the same time, Leonardo conducted an autopsy on a child and observed that the same type of blood vessels was not blocked.

In Leonardo’s drawings, he also discovered ways to depict features from eight angles, through cross-sections and many cutaway drawings that revealed multiple layers of muscles and tissues, exposing each structural layer. Leonardo was particularly fascinated by the human eye. He studied the structure of the eyes, their connection with other internal organs, and their precise functioning. To understand the human eye better, Leonardo developed a technique for dissection by immersing the eye in egg white and boiling it to make the specimen firmer and easier to handle. Rejecting the prevailing belief of his time that the eye emitted invisible rays, Leonardo argued that the eye is a sensory organ that can “see” through reflected light.