A new study involving researchers from the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford, published on February 15, 2022, in the journal Trends in Ecology & Evolution, indicates that social extinction is the disappearance of species from our collective memory and attention. Species can vanish from our society, culture, and discourse simultaneously, or even before they become biologically extinct due to various human actions.

With only a few specimens in museum collections, the Honshu wolf, also known as okami (Canis lupus hodophilax), is beginning its gradual process of social extinction in Japanese society.

“Species go extinct twice – once when the last individual breathes its last, and a second time when the collective memory of the species fades away” – a paraphrase of a quote by both Banksy and Irvin Yalom.

A group of international and interdisciplinary scientists discovered that whether a species becomes socially extinct depends on many factors. These may include its appeal, its symbolic or cultural values, how long ago it became extinct, and how distant and isolated it is from humans.

The thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) and the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) both lived on the Australian continent during the mid-Holocene and were lost from the memories of Indigenous peoples, while they still exist in Tasmania, where they remain significant and prominent to local communities.

Dr. Diogo Verissimo, a researcher in the Department of Zoology at the University of Oxford and co-author of the study, stated:

“Social extinction occurs not only in species that have gone extinct but also in those still living among us, often due to cultural or social changes, such as urbanization or societal digitization, which can completely alter our relationship with nature and lead to collective amnesia.”

One example researchers provided is the replacement of traditional herbal medicine with modern medicine in Europe. This is believed to have diminished common knowledge about many medicinal plants, leading to their social extinction.

As more species become threatened or extinct, they also become isolated from humans. This leads to the extinction of experience – the gradual loss of our daily interactions with nature. Over time, such species may completely disappear from human memory.

Efforts to reintroduce extinct species, such as the Eurasian beaver (Castor fiber) in the UK, may be affected by their absence in collective memory as natural components of the ecosystem, and thus receive less public support.

For instance, studies conducted among communities in southwestern China and Indigenous peoples in Bolivia have shown a loss of local knowledge and memory regarding extinct bird species.

However, the opposite can also occur. Dr. Uri Roll, a co-author and researcher at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, explained: “Species can also be popularly referenced even after they go extinct, or even become more well-known.”

“However, our perception and memory of such species gradually become distorted, often becoming inaccurate, stylized, or simplified, and detached from the actual species.”

For example, after the Spix’s macaw went extinct in the wild, children from local communities within its former range mistakenly believed that the species resided in Rio de Janeiro simply because of its appearance in the animated film Rio.

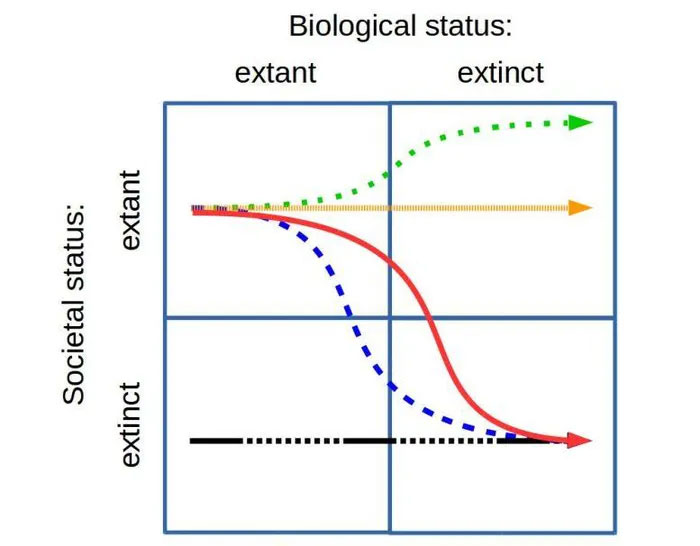

Main trajectories of social extinction.

Dr. Ivan Jaric, the lead author of the study and a researcher at the Czech Institute of Biology, stated: “It is important to note that most species cannot truly become socially extinct simply because they never had a social presence to begin with.”

“This is common among species that are obscure, small, difficult to access, or inaccessible, especially among invertebrates, plants, fungi, and microorganisms – many of which have not been formally described by scientists or are unknown to humanity,” Dr. Jaric continued.

Dr. Josh Firth, a co-author of the study and a research fellow at the Department of Zoology at Oxford, said:

“Social extinction can impact conservation efforts aimed at protecting biodiversity as it may diminish our expectations of the environment and our perception of its natural state, such as being standard or relatively healthy.”

Further studies will now assess how social extinctions can create misconceptions about the severity of threats to biodiversity and the actual extinction rates, while also diminishing public support for conservation and restoration efforts, such as reintroducing the Eurasian beaver to the UK.

“Social extinction can reduce our will to pursue ambitious conservation goals. For example, it may decrease community support for reintroduction efforts, especially if such species are no longer present in our memory as natural components of the ecosystem,” Dr. Jaric added.