If Earth had rings like Saturn, it would feature a band encircling the equator. This band would appear differently when viewed from various locations around the planet.

From the equator, the inner ring would appear as a straight line on the horizon.

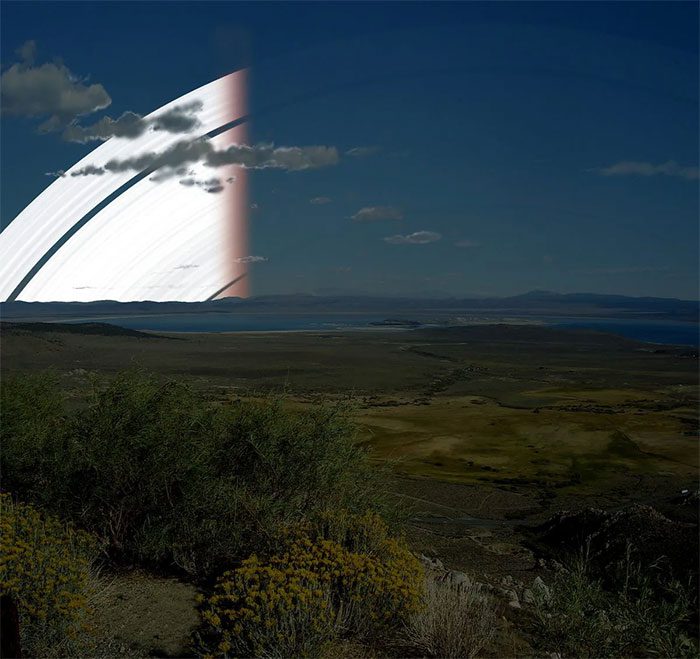

Have you ever wondered what the sky would look like if Earth had rings like Saturn? Illustrator and author Ron Miller has created stunning visuals that depict how various landscapes on our planet would appear with such a feature. These images are based on scientific calculations and realistic perspectives, providing us a glimpse of an alternate Earth that is both familiar and strange.

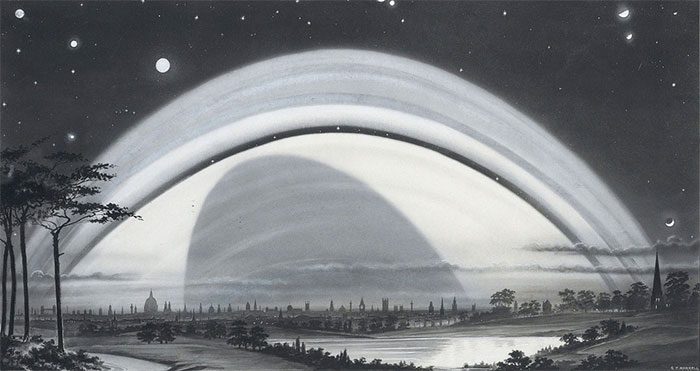

Miller told Earthly Mission: “The inspiration for these artworks was largely drawn from illustrations created about 100 years ago by early space artists. Among them were George F. Morrell and Scriven Bolton, a pair of British artists who produced many astronomical illustrations in the 1920s. Their works included views of how rings similar to Saturn would look if they surrounded Earth.”

Saturn, known as the jewel of the Solar System, has captivated astronomers and space enthusiasts with its beautiful and iconic rings.

Miller added: “I think it would be fascinating to show how asteroid rings would look from different positions on our planet.” For example, at the equator, they would appear as a bright white line splitting the sky, while at the poles, they would be barely visible.”

Miller also illustrated the rings from various latitudes and landscapes, from Atlantic City to the ruins of the Maya in Guatemala, all the way to the Tropic of Cancer, vividly bringing to life the mesmerizing sight of Earth adorned with the majestic rings of Saturn.

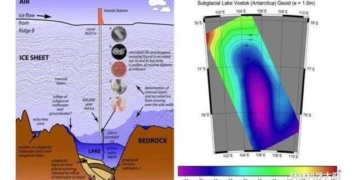

Scientists believe Earth once had an asteroid belt, albeit billions of years ago. They hypothesize that the belt formed early during the creation of Earth and the Moon. There is an accepted theory that a planet named Theia collided with Earth in the distant past. This collision caused a massive explosion, powerful enough to eject millions of tons of debris into Earth’s atmosphere, eventually forming a ring that gradually coalesced into the Moon we see today.

If Earth’s original ring still existed, its shape would change based on your location. It would depend on the latitude where you stand. The ring would primarily be parallel to Earth’s equator and visible in the sky from east to west. Near the equator, the ring would look like thin slices of light stretching straight up from the horizon, extending across the sky to the farthest point visible to the human eye.

The further from the equator, the more the shape of the ring changes. The ring would become more pronounced and wider. Much like the Moon, the ring would reflect sunlight back to Earth at night. And perhaps due to its extensive spread across the sky, the ring would reflect a significant amount of sunlight, ensuring that our planet would never be completely shrouded in darkness, but rather experience a gentle twilight. Of course, during the day, the ring would likely cause a surge in light levels on Earth.

Ignoring the aesthetic aspect, having an asteroid belt would pose significant challenges to our current satellite infrastructure. They could interfere with satellite orbits, telecommunications missions, and space exploration. The presence of a dense ring could also create navigational hazards for spacecraft entering or leaving Earth’s atmosphere. Space agencies would need to recalibrate and possibly redesign spacecraft to navigate safely in such an environment, not to mention the impacts on research vehicles like the International Space Station.

The rings around Earth would undoubtedly have significant impacts on the climate. These massive fragments could act as a shield in some areas, potentially blocking many rays of sunshine from reaching Earth’s surface. This could lead to cooler temperatures in certain regions, especially those directly beneath the thickest parts of the ring. Conversely, sunlight reflected from the rings could cause a warming effect in other areas. Climate models would need to account for these new variables, complicating our understanding of global weather patterns.