German experts have utilized Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) technology to scan the area of the Qin Mausoleum. The results indicate that this site is “impregnable.”

The Discovery Process of the Tomb of Qin Shi Huang

Qin Shi Huang, as the first emperor in the history of unified China, established the first centralized multi-ethnic feudal state and also coined the term “emperor.” He is often described as cruel and tyrannical, a murderer and a despot, yet not a foolish king. Speaking of the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, the construction required considerable time and effort, and it is said that many emperors began restoring his tomb immediately after ascending the throne. Overall, it took two or three years to complete the construction. After his death, not only his gold and silver jewelry but also living individuals were buried with him.

The tomb of Qin Shi Huang is a magnificent underground wonder. Although it conceals a colossal treasure, it remains intact, untouched for 2,000 years. The mausoleum was constructed north of Li Mountain, in Xi’an city, Shaanxi province, China.

The overall architecture of the tomb was designed by Prime Minister Li Si (284 BC – 208 BC), a key aide to Qin Shi Huang, and construction was strictly supervised under the management of General Zhang Han. The mausoleum’s construction began in 246 BC but was not completed until the second year of the Qin dynasty (208 BC) — a total of 38 years later.

According to the “Records of the Grand Historian: Qin Shi Huang” (Volume 6, compiled and published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences), it is estimated that over 720,000 farmers and soldiers participated in building the tomb of the Qin Emperor, which is eight times the number of people who built the Great Pyramid of Giza!

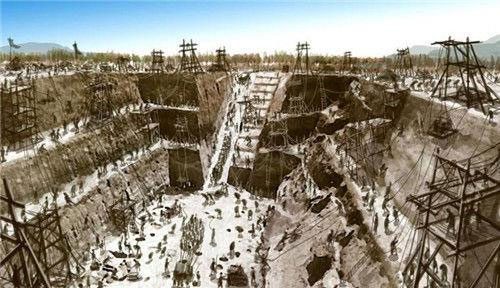

Excavation of the tomb of Qin Shi Huang. (Illustration: Sohu).

In March 1974, in Shaanxi province, a farmer digging a well unexpectedly discovered many shards of ancient pottery in his yard. He had stumbled upon the burial site of the army that guarded the Qin mausoleum, paving the way for scientists to access what is known as the “eighth wonder of the world.”

According to data published on the official website of the People’s Republic of China, the Qin Mausoleum is approximately 40 meters high. The internal layout resembles the capital of Handan, divided into an inner city and an outer city, with the inner city having a circumference of about 2.5 km and the outer city about 6.3 km.

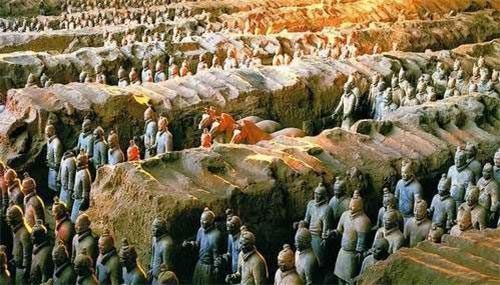

Burial pits for the terracotta warriors and horses are located to the east of the mausoleum. In 1974, four burial pits were excavated, covering a total area of over 25,000 square meters.

As of 1974, only a few tunnels leading into the “inner city” of the tomb had been excavated.

The remaining part – the center of the mausoleum – remains intact to this day and is strictly protected by the government. So why is that?

The terracotta soldiers displayed in the Qin Mausoleum. (Illustration: Baike).

The Capital “Not Meant for the Living”

In the “Chronicles of the Qin King” by the Han Dynasty’s Grand Historian Sima Qian (145 BC – 86 BC), there are detailed records about the Qin Mausoleum, including a passage that piques curiosity: “Through the three streams, below the ground there are hundreds of palaces and precious artifacts stored, commanding the statues to face east, those who might approach can only see shadowy reflections.”

First of all, “through the three streams” can be understood as “crossing three streams,” describing the depth of the tomb underground.

According to data published by the Ministry of Culture of China, the thickness of the 76m layer of soil covering the Qin Mausoleum has led to excavation costs reaching 60 billion yuan.

These records also indicate the significant treasures hidden deep within the tomb of Qin Shi Huang. However, the phrase “those who might approach can only see shadowy reflections” suggests that this is an impregnable place, and the treasures inside are artifacts that cannot be excavated.

Indeed, archaeologists discovered something very important during the excavation of the warrior pits: The terracotta warriors and horses, originally vibrant in color, have oxidized after being unearthed, losing their original hues and turning brown as seen today.

The terracotta soldiers originally vibrant in color before oxidation. (Illustration: Sohu).

The “Impregnable” Underground Kingdom

In the “Records of the Grand Historian,” Sima Qian wrote: “Using mercury to create hundreds of rivers and seas,” describing that deep within the Qin Mausoleum exist hundreds of thousands of mercury mountains and rivers, flowing continuously like an endless cycle. This information is not only found in historical texts but also verified by German scientists at the end of the last century.

In the 1980s, German experts used MRI technology to scan the Qin Mausoleum area. The results indicated that this site has a mercury content many times higher than normal.

The tomb of Qin Shi Huang also recorded temperature anomalies, suggesting that the anti-theft mechanisms inside may still be operational. This finding is considered a major discovery, providing scientists with further evidence to support the hypothesis of mercury existing within the tomb.

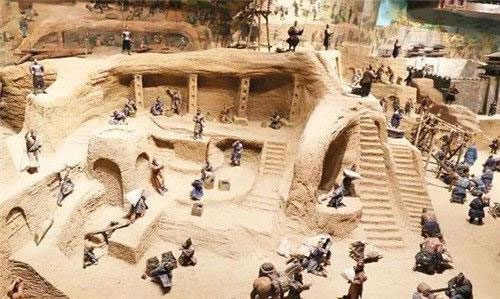

Simulation of the interior of the tomb of Qin Shi Huang. (Illustration: Sohu).

Mercury is a volatile metal that can easily separate into small droplets and disperse widely. Its evaporation rate increases significantly with rising temperatures and wind speeds.

Although mercury itself is less toxic, when it evaporates, its compounds and salts are highly toxic, potentially causing damage to the nervous, digestive, respiratory, immune systems, and kidneys, affecting the health and lives of those exposed.

Thus, a major question arises: What consequences will a large area filled with mercury, such as the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, have when excavated on the surrounding areas?

In light of this risk, the National Cultural Heritage Administration of China has issued a directive: To halt all plans for excavation within the Qin Mausoleum and continue to protect and preserve its current state.

Most archaeological work today at the tomb of Qin Shi Huang involves rescue excavations, primarily aimed at safeguarding cultural relics. By the end of the 20th century, the consensus within the international archaeological community was to cease further excavations of the tomb.