Research on the tooth replacement habits of a small marsupial species may have uncovered valuable data about human teeth.

Throughout their lives, humans only have 52 teeth – 20 primary teeth and 32 permanent teeth after one replacement.

However, not all vertebrates exhibit this tooth replacement behavior. Some rodent species never replace their teeth, while others, such as fish, amphibians, and reptiles, can replace their teeth multiple times throughout their lives.

Throughout their lives, humans only have 52 teeth.

So, why has nature only “allowed” humans to replace their teeth once, facing the risk of permanent tooth loss if adult teeth are damaged? Scientists are still trying to explain this, but a recent discovery about the tammar wallaby may shed some light on this question.

This species was revealed due to advancements in 3D scanning and imaging technology, alongside fruit bats, as some of the mammals that exhibit a unique tooth replacement method despite their common ancestors being species that replaced teeth multiple times.

How Do Humans Replace Teeth?

Human teeth begin to develop during the 6th to 8th week of embryonic development when a strip of tissue in the gums called the primary dental lamina begins to thicken. Along this strip of tissue are clusters of special stem cells located at the future tooth sites, known as placodes.

The placodes then develop into teeth, completing with dentin and enamel. Ultimately, they will “emerge” from the gums. The incisors will erupt first when a child is about 6 months old.

The teeth that grow from this initial eruption from the primary dental lamina are called primary teeth. Permanent teeth, on the other hand, grow differently. A branch of tissue known as the secondary dental lamina will emerge from the primary teeth, and these tissues will develop into new teeth similar to how apples grow on trees. Surprisingly, permanent teeth begin to develop even before we are born, but it takes many years to shape and eventually appear.

Molars typically replace first at ages 6-7.

Tooth replacement occurs when the permanent teeth are large enough to “push” the primary teeth out, taking their place as the complete set of teeth for the rest of life. Molars usually replace first at ages 6-7, while wisdom teeth appear last, at ages 17-21.

Most mammals only replace their teeth once in their lifetime, like humans. Some special groups, such as rodents, never replace their teeth, while others, like hedgehogs, may not even develop teeth.

Lessons from the Tammar Wallaby

The tammar wallaby also undergoes a single tooth replacement like humans. Scientists believe that their tooth replacement process is similar to ours; however, observations dating back to 1895 show some differences.

For example, humans replace incisors, canines, and premolars, while this species only replaces premolars (the transitional teeth between canines and molars).

Skull of the tammar wallaby.

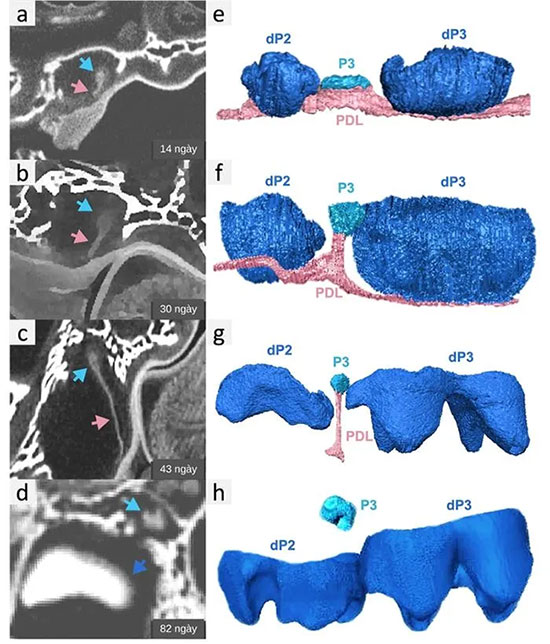

Researchers at Monash University and the University of Melbourne have observed the teeth of this marsupial from embryonic stages to adulthood. Using a technique called diceCT, which is a form of tomography, they discovered some surprising findings.

The teeth replaced in the tammar wallaby do not emerge from the secondary dental lamina; instead, they are actually primary teeth that grow slowly from the primary dental lamina. This means they do not grow and replace teeth in the way we have traditionally thought.

Tooth development process of the tammar wallaby. The model shows that the P3 tooth is a primary tooth that grows 47 days slower than the dP2 and dP3 teeth.

One explanation for the slow growth of primary teeth may relate to the common ancestry of mammals that also replaced teeth multiple times.

Unlike most mammals, many other animals such as fish, amphibians, or reptiles can replace their teeth multiple times throughout their lives. Mammals lost this ability about 205 million years ago.

The reason mammals cannot continue to replace teeth is that the dental lamina has degenerated after the second set of teeth has erupted, while this structure remains active in species that replace teeth multiple times.

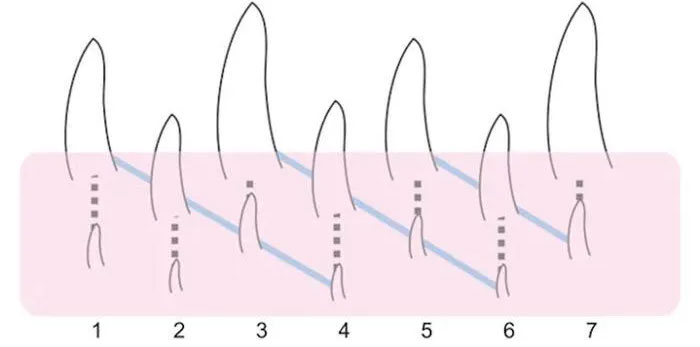

In non-mammal species, teeth grow continuously in alternating waves.

It is noteworthy that in species that replace teeth multiple times, the tooth growth occurs in alternating “waves,” known as “Zahnreihen.” The slow tooth growth of the tammar wallaby demonstrates that traces of “Zahnreihen” still exist in modern mammals, providing evidence that humans, as mammals, also have ancestors that developed teeth in this manner.

Why Don’t Mammals Replace Teeth Multiple Times Anymore?

The crux of the matter is that by growing teeth according to “Zahnreihen,” the jaws of species that replace teeth multiple times face a problem: they never have enough teeth. There will always be gaps in the jaw because that position has not yet reached the wave of growth. This means that their teeth can bite and tear but cannot chew.

Reptiles like crocodiles or snakes have a different metabolic mechanism than mammals.

Mammals sacrificed the ability to replace teeth throughout their lives to have a complete, permanent set of teeth, allowing them to chew food into smaller, more digestible pieces—particularly suitable for species with fast metabolism and high energy needs.

Reptiles like crocodiles or snakes have a different metabolic mechanism than mammals. They can survive for a year on a single large meal. In contrast, mammals like shrews can starve within a few hours, making the need to grind food for quick digestion vital for them, while it is not necessary for reptiles.

Moreover, with the “unintentional” nature of the wild, the survival of a mammal to old age and losing all teeth to the point of difficulty eating is a “luxury,” as they often died while still having enough teeth due to disease or predation. For this reason, the “flaw” of having only 1-2 sets of teeth throughout life is not evolutionarily significant, and thus it has persisted for hundreds of millions of years.