Marcus Licinius Crassus is considered one of the first tycoons of the ancient world, a modern archetype from thousands of years ago for reaching the pinnacle of power and wealth.

In Rome, Crassus’s wealth became legendary. The Roman author Pliny the Elder estimated that his net worth was nearly equivalent to the entire annual budget of the Roman Republic. It is difficult to compare this to the present day, but for example, the budget of the United Kingdom last year was over one trillion pounds.

It is estimated that his wealth, if converted to today’s standards, could amount to $12 billion – largely derived from real estate, slave trading, and mining.

However, today in the West, people are more familiar with Croesus, a king of Lydia who lived 500 years before Crassus. The wealth of this powerful man and “landlord” of Rome seems to have faded into obscurity.

“Tycoon” with financial prowess from the future

A primary motivation for the successes of ancient times – an era when sudden death lurked with countless dangers – was the desire to be recorded in history for posterity’s remembrance.

Despite this, Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of the most prominent political figures of the late Roman Republic, did not secure the historical position he desired, nor did his career seem to promise. Every child knows the name Julius Caesar and the name of Pompey; yet Crassus – the third member of the “Triumvirate” of Rome – has gradually fallen into oblivion.

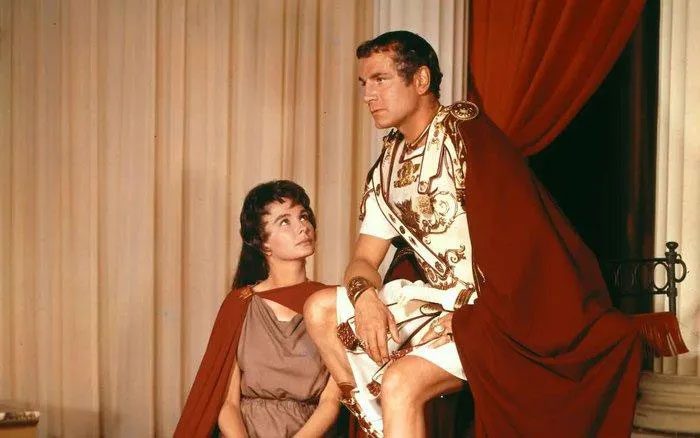

Crassus depicted in the 1960 film Spartacus.

But this does not diminish the influence of the “first tycoon” in history. With persistence and remarkable skills, Crassus navigated the dangers and intrigues of Roman politics to rise to its pinnacle, only to overreach himself, launching a disastrous military campaign against the Parthians that cost him his life and reputation.

Crassus’s political career did not have an easy start. He was born into a patriarchal family: his father followed in his grandfather’s footsteps, serving as a consul, one of the two heads of the Roman government.

However, Crassus’s father took his own life after becoming an opponent of the general Gaius Marius. Crassus fled into exile in Spain, where he hid in a cave for eight months, surviving on supplies from a friend.

At just under 30 years old, he began recruiting soldiers in Spain and joined Sulla, Marius’s main rival, in Greece. This was when his outstanding qualities began to flourish: resilience, boldness, ambition, and a willingness to take risks.

Fortune smiled upon Crassus when Sulla’s victory over Marius’s forces and his rise to dictatorship encouraged Crassus to build his own political power. In the ensuing chaotic and bloody purge, a list of “accusations” against Sulla’s opponents was drawn up, condemning them to death and confiscating their properties for the state.

Crassus seized the opportunity to purchase large amounts of real estate at low prices during public auctions. Wealth in ancient Rome primarily came from land ownership as agriculture dominated the economy. Crassus understood this and began to become the largest landowner in Rome.

Unusually, he also owned vast urban properties in Rome. Crassus’s real estate empire included everything from grand houses to slums and was managed with an extraordinary level of professionalism. He assembled teams of specially trained slaves dedicated to specific functions, including those equivalent to private firefighting services, meeting the “needs” of Rome at the time.

Fires frequently broke out among densely packed and often poorly constructed buildings. Crassus’s people would appear and offer to buy burning buildings from their desperate owners (or their neighbors) at a low price – before setting to work extinguishing the flames.

Like Peter Rachman, the notorious slum landlord in London during the 1950s, Crassus was not a man burdened by trivial considerations. This did not make him unique in Rome; however, his highly organized commercial activities certainly did. In this sense, he was far ahead of his time.

Wealth in ancient Rome primarily came from land ownership as agriculture dominated the economy.

Through loans and financial support, Crassus transformed his increasingly large fortune into a network of influence. However, he faced a problem: the money earned through business dealings was looked down upon by the Roman aristocracy. According to some contemporaries, his pursuit of finance was seen as disreputable.

Crassus was described as being so financially greedy that the famous Roman philosopher and orator Cicero remarked that Crassus would leap the entire length of the Roman Forum just to be mentioned in a will.

Land was not the only form of wealth. Gold and silver were also speculative assets, just like slaves – and these could be most effectively acquired through foreign conquests.

Pompey achieved this spectacularly with his victories in the Near East. The amount of spoils Pompey brought back after his successful campaign against Mithridates of Pontus was so great that “Crassus could not deny that Pompey was richer.”

The Downfall from Hubris and Envy

Crassus was acutely aware that wealth could not be solely about money; it also had to encompass honor, which could only be attained through military conquest. Crassus longed to be celebrated for a victory – a triumphant parade through Rome – something he had witnessed his father achieve and which had marked the names of his rivals, Pompey and Caesar, in a way that no one could succeed in business.

This was why he launched an unnecessary and disastrous campaign against the king of Parthia, a powerful and mysterious enemy.

The swift consequences followed. Rome, under Crassus’s command, suffered a disastrous defeat in the invasion, culminating in the Battle of Carrhae, where the Parthian cavalry triumphed effortlessly over their adversaries, marking a bitter defeat for both the empire and Crassus. This failure also led to the demise of “the richest man in Rome” when he was subsequently killed after failed negotiations.

Crassus (right) and Caesar in a 2010 television series.

The story of Crassus is worth recounting. He played a larger role than most others at a crucial moment in Roman history, when its power was merging but the old political structure was failing.

His world is in some ways entirely alien to us: a tragic, brutal, and short life. It is said that the Parthians filled his mouth with molten gold as a form of humiliation for his greed.

Yet, Crassus is also a strangely modern figure. His skills as a reformer, investor, financier, and planner would likely make him an outstanding entrepreneur or executive today. He used his talents to follow an unusual path that nearly led him to the pinnacle of Roman politics.

But he could not escape the constraints of his era: that summit was reserved for the conquering heroes, not a role assigned to a “businessman” or “tycoon.”