Like the Temple of Literature or the Hanoi Opera House, the Hanoi Children’s Palace is an important cultural institution, with each structure marking a historical period of Hanoi – the modern era of Vietnam. With an architectural language entirely distinct from those two cultural landmarks, the Palace deserves to be a heritage representative of the historical phase in which it was built. However, recently, with the commencement of the new children’s palace project in Hanoi, many people worry that the Children’s Palace, with a history spanning over half a century, will no longer be the cultural home for the children of Hanoi. As someone who has spent many years researching and contemplating the Hanoi Children’s Palace, Associate Professor Dr. Architect Phạm Thúy Loan, a representative of Docomomo Vietnam, has written to share her thoughts on this issue.

Hanoi Children’s Palace

Associate Professor Dr. Architect Phạm Thúy Loan, representative of Docomomo Vietnam

In October 2015, I represented Vietnam at the launch workshop of the research program on Modern Architecture in Southeast Asia in Tokyo, Japan. The program, named mASEANa, included over 50 delegates from Southeast Asian countries, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, including the president of Docomomo International, Professor Ana Tostoe, and many scholars and researchers of modern architecture from around the world. Among the ten modern works of Vietnam that we chose to present to international friends was the Hanoi Children’s Palace (Cung TNHN). Amid hundreds of modern architectural works from various countries showcased at the workshop, the Hanoi Children’s Palace received special attention. Shortly thereafter, a representative from the Getty Cultural and Educational Foundation in the United States, one of the most prestigious organizations in the world that funds research and preservation activities in the arts and culture, proactively approached me and said, “Your Hanoi Children’s Palace is a very impressive work. I think you should prepare a dossier to submit to the Getty Foundation to receive technical and financial support.” In the ‘Keep It Modern’ program for 20th-century architectural works, the Getty Foundation annually selects ten outstanding modern architectural works from all continents around the world, providing funding and technical support for research and preservation activities to raise global awareness of the value, historical significance, technology, and ideas of these modern architectural works; while sharing practical experiences in research, preservation, and management of these works through specific cases.

After the international workshop and that valuable exchange, I returned home filled with excitement and quickly began preparing the dossier for the Hanoi Children’s Palace to submit to Getty. For me personally, the Hanoi Children’s Palace is no stranger; in fact, it is very familiar because I spent my childhood participating in art club activities there (around 1984 to 1990) and explored every corner of that “cultural castle for children.” Accompanying me in preparing the dossier were Architect Trương Ngọc Lân (from the University of Civil Engineering), an expert in architectural history, Architect Nguyễn Hà (from Arb East – Switzerland), and several other colleagues; and one extremely important person who must be mentioned is Architect Lê Văn Lân, the designer and chief architect of the project.

Docomomo Vietnam

The initial dossier for the Hanoi Children’s Palace was completed and sent to the Getty Foundation by the end of December 2015, and it was quickly included in the short-list for the next round. To provide you with more information about the Palace and its author, we would like to share the main contents of the dossier that was prepared and sent to the Getty Foundation as follows:

General Information about the Project

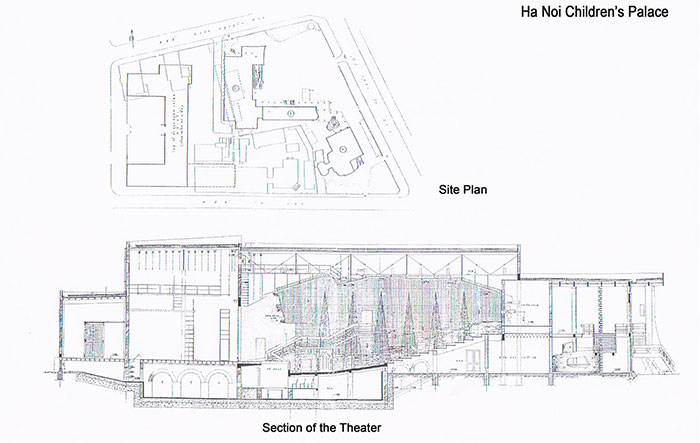

- Project Name: Hanoi Children’s Palace

- Design Year: 1974

- Completion Year: 1976

- Location: 36 – 38 Lý Thái Tổ, Hoàn Kiếm District, Hanoi

- Function of the Project: A venue for organizing classes, cultural and artistic clubs, and sports activities for the city’s youth and children, with over 60 years of operation

- Managing Agency: Hanoi Youth Union, under the Hanoi People’s Committee

- Site Area: 1.2 hectares

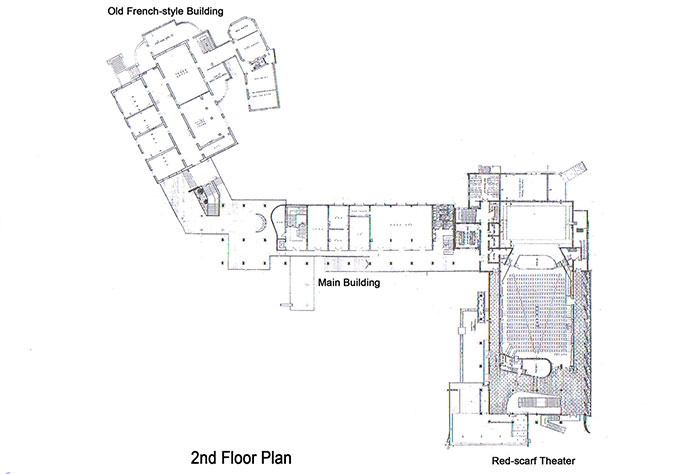

- The Palace comprises 3 building blocks:

- Administrative block (the existing colonial-era building on the site)

- 5-story functional building (for classrooms and clubs, with a total floor area of 7,000 m²)

- 520-seat theater (Red Scarf Theater)

1. Introduction to the Project Designer

Architect Lê Văn Lân

The author of the project is Architect Lê Văn Lân, born on February 20, 1938. He graduated from the first class of Architecture and Construction at Hanoi University of Technology – the precursor of the University of Civil Engineering – in 1959. In 1960, he worked at the Department of Civil Design and at the Department of Urban and Rural Planning, under the Ministry of Construction.

In 1961, he interned in Moscow on planning; from 1963 to 1967, he worked at the Hanoi Design and Planning Institute; from 1968 to 1972, he studied in the German Democratic Republic on cultural project design; from 1973 to 1980, he served as Deputy Director of the Hanoi Construction Design Institute; and from 1981 to 1998, he was the Director of the Hanoi Construction Design Institute/ Director of the Urban Civil Architecture Consulting Company. He was also a member of the Executive Committee of the Vietnam Architects Association from 1983 to 2005; participated in teaching and supervising graduation projects for architecture students; Director of the Urban Civil Architecture Company; and a member of the Hanoi City Planning Appraisal Council.

2. Significance and Multifaceted Values of the Hanoi Children’s Palace

The Hanoi Children’s Palace is one of the outstanding modern works of Vietnam, born in a specific and extremely difficult historical context. To fully appreciate the significance and value of this architectural work, we need to place it in the unique context of its creation, when Vietnam had not yet escaped from war and was pouring all its efforts into the liberation of the South and the unification of the country, while also striving to assert its intellect and capabilities in nation-building; architecture has always been a wonderful “tool” for expression.

In that historical context, the Hanoi Children’s Palace can be seen as a work of multifaceted significance.

Social Significance of the Children’s Palace

- The Cultural House is one of the social institutions, a type of social infrastructure very characteristic of socialist countries; the cultural palace for children in Hanoi – the first modern structure prioritized for children during wartime – reflects the state’s special concern for future generations, embodying a profoundly humanitarian perspective.

- The project was designed, constructed, and built by Vietnamese architects, experts, and workers during the difficult final stages of the war, affirming independence and a strong intellectual and capable effort.

- In terms of location, the project is situated in a spacious area, right next to the Hanoi People’s Committee and Hoàn Kiếm Lake, the heart of the nation, demonstrating a special concern for the cultural, spiritual, and physical development of children.

Architectural Significance

The project is a prominent and ingenious architectural work, representing the “self-assertion” of modern Vietnamese architecture. The complex includes an Administrative House (a colonial villa that existed on the site), the main functional building, and the Red Scarf Theater.

Some of the main and outstanding architectural features of the Functional Block are as follows:

The architectural language of the modern building is simple, with a tight layout, completely breaking away from the colonial architectural language or previous architectural trends. The building almost opens up on the first floor, bringing the outside space into the spacious main lobby; large outdoor staircases lead up to a wide lobby on the second floor without enclosing walls, creating enjoyable terrace spaces for children both indoors and outdoors. (There is a crescent-shaped bench made of granito concrete that is very charming. Back then, I was studying art but still longed to learn ballet. When I peeked at the ballet class practicing, I often went to this crescent bench to practice my moves, but it was so painful that I had to abandon my dream of dancing). The floor plans of the levels are resolved differently on the same structural system, ensuring adaptability to the different usage requirements of the clubs.

In terms of structure and materials, the main structural system of the building is reinforced concrete frame with brick walls; a steel truss system is used for the theater (Red Scarf Theater). The project utilizes all locally available materials, including stones damaged in the war, bricks, and leftover tiles from other construction projects during the extremely scarce conditions of war.

Regarding climate adaptation solutions, architect Lê Văn Lân has left his international colleagues in awe. The structure is not aligned parallel or perpendicular to the road as is typical in conventional urban planning, but instead is positioned at an open angle of about 60 degrees to the axis of Lý Thái Tổ Street. This design creates a broad visual field, allowing for a full appreciation of the building’s form from both Lý Thái Tổ and Trần Nguyên Hãn Streets. The orientation of the building also provides the most ideal ventilation conditions for Hanoi’s climate. The design incorporates a large concrete flower wall that covers nearly the entire facade, effectively blocking sunlight and reducing heat radiation while still ensuring adequate light and ventilation. This is one of the clever and effective passive energy design techniques, developed from the application of the “dai panel” solution in traditional Vietnamese residential architecture. This technique is also a hallmark of modern architecture in the hot and humid tropical regions of Vietnam and some Southeast Asian countries—a blend of global trends with local conditions in the late 20th century. In the Youth Palace, the windows are maximally enlarged on each floor to facilitate air circulation and harmonize with nature both visually and in terms of airflow.

For the first time in Hanoi, the author proposed a rooftop flower garden; however, due to budget constraints, the idea could not be realized. The project also proactively utilized and preserved all existing old trees within the premises (which, after decades, the renovation efforts in 2016-2017 failed miserably, resulting in the death of two ancient trees during the renovation process, whether accidentally or intentionally).

Some other interesting features of the project include: a combination of architecture with artistic ceramic mosaic decorations on columns, wall paintings, and stained glass; a clever and delicate connection between the new architecture (the main building) and the old French architectural structure (the administrative block) through a corridor bridge behind the terrace lounge mentioned earlier. The palace was assisted by Czechoslovakia in terms of equipment and play items, including the elevator; it was also the first building to have an elevator installed in Hanoi (excluding the elevator installed by the French at the Metropole Hotel at the beginning of the century, which soon malfunctioned).

As for the Red Scarf Theater, this building also contains many fascinating stories. It was the most meticulously and complexly designed theater of its time, with 520 seats. Architect Lê Văn Lân studied hundreds of different theater models worldwide to design this Red Scarf Theater. The theater required a bomb shelter, one of the challenging yet essential requirements at that time. The stage had a music pit (under which there was space for installing a lift for the pit floor, though due to the economic conditions of that period, it was not feasible to install it), with spotlight rooms on either side of the stage and a lighting rig above the front stage, a performance bridge in front of the stage, and dressing and makeup rooms.

Architect Lê Văn Lân shared with us that he nearly lost his architect license and professional certificate when he refused a request from the city leadership at the time to simplify the theater design to shorten construction time and save costs. At that time, he even accepted personal losses and damage to his reputation to defend his design to the end. Truly, he is a shining example of professional integrity. In the end, he triumphed, and the theater design was understood and respected.

Project drawing.

Functional Significance

For over 40 years, this building has truly been the cultural world of childhood for countless generations of children in Hanoi. Many generations of Vietnamese artists (famous singers, painters, actors) have grown up from this artistic cradle: singers Thanh Lam and Hồng Nhung were once child music stars of the palace, admired by generations of the 70s and 80s. The images, spaces, and memories of the Children’s Palace have unconsciously become a part of Hanoi’s memory in the hearts of its people. This simplicity is what creates the ‘soul of the place’ and the ‘identity’ of a city.

Like the Temple of Literature or the Grand Theater, the Hanoi Children’s Palace is also an important cultural institution. Each building marks a historical period of Hanoi. The Children’s Palace represents modern Vietnam, the period of independence, nation-building, and the advancement towards socialism. With an architectural language entirely different from those two cultural buildings, the Palace deserves to represent the historical period in which it was created, serving as a tangible continuation of history that tells a continuous story of a fluctuating Hanoi.

After over 40 years of operation, the building is currently overloaded as it receives an increasing number of children every year for learning and training. Therefore, it is essential for a city of 10 million like Hanoi to have more children’s palaces, cultural houses, playgrounds, and gardens. However, it must be emphasized that this does not mean that when a new building is constructed, the old one can be demolished—especially when the old building has value and is being utilized at a very high capacity. No, that is unacceptable in the case of the Hanoi Children’s Palace.

In summary, from various perspectives, we can assert that the Hanoi Children’s Palace is an important building with significant meaning in many aspects: It is a long-standing nurturing ground for artistic talent among Hanoi’s children; it is one of the first truly modern architectural works in Hanoi, designed by a Vietnamese architect and built by Vietnamese people—symbolizing the rise and self-assertion on a national scale in architecture, construction, and culture. The Hanoi Children’s Palace deserves to be recognized as a ‘DISTINCTIVE MODERN ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE OF VIETNAM’ that can stand alongside modern architectures worldwide (according to the approach of international professional organizations) and at the very least, it deserves to be classified as a ‘building of special value’—according to the recently enacted Architecture Law effective from July 2020. It needs our utmost respect and protection.

Foreword

1. The Hanoi Children’s Palace ultimately could not participate in the ‘Keep It Modern’ program of the Getty Foundation to stand alongside modern architectures worldwide, due to both objective and subjective reasons. At the beginning of 2016, the palace underwent repairs due to deterioration after many years of use. The renovation project, although not altering the structural integrity of the building, did not consider historical aspects and heritage preservation, thereby significantly changing many historical characteristics through the building’s architecture. Specifically: The rows of columns and walls using a surface material of washed stone (fine gravel) characteristic of the 70s and 80s were ‘generously’ replaced with Thanh Hoa granite cladding; the old steel-framed glass doors were replaced with the currently popular aluminum and glass systems; the installation of fire-resistant doors (as per new fire safety standards) changed the original design and greatly affected the usability of the building; and many other renovation details, while possibly enhancing safety, did not take historical factors into account.

We need to understand that one of the important meanings of preservation and restoration work on historically valuable buildings is (on one hand) to ensure the building’s safety and sustainability, but it must not alter original elements, so that the building can “tell the historical story” of the era in which it was created through itself: from structure to detail, materials, and many other factors.

With the changes from this renovation project, we proactively withdrew the Hanoi Children’s Palace from the Getty 2016 selection list as the criteria for originality were no longer met.

2. In light of concerns regarding the fate of the existing Hanoi Children’s Palace when information about the commencement of a new children’s palace project emerged in the media, there have been numerous expressions of worry and dissatisfaction if the old Palace were to be demolished and the land exploited for group interests; and the community’s disappointment at the unclear response from the city that “there are no plans for the old palace”; we will soon submit to the Hanoi Department of Planning and Architecture, the City Architecture Planning Council, the Hanoi People’s Committee, the Vietnam Architects Association, and the Architecture Planning Department of the Ministry of Construction a presentation of the values along with historical documents about the old Hanoi Children’s Palace (as analyzed above), and request that relevant authorities promptly carry out the procedures to list this building as ‘Architecture of Special Value’ (according to the Architecture Law) to establish a specific, effective preservation plan. We will also send information about the Hanoi Children’s Palace to the Docomomo International organization, requesting to include the palace in the ‘Heritage in Danger’ list so that experts and representatives from international organizations can advise the authorities and management levels of Hanoi on the need for a preservation and protection plan for this valuable modern architectural work.

(1) Docomomo Vietnam is a research and preservation group for modern architecture in Vietnam, established as a national representative organization of Vietnam under Docomomo International, under the auspices of the Vietnam Architects Association.

(2) mASEANa (modern ASEAN architecture) is a research program focused on modern architecture in Southeast Asia, involving experts from 10 Southeast Asian countries and Japan. It is funded by the Japan Foundation and other funds, under the auspices of Docomomo Japan and Docomomo International. mASEANa ran from 2015 to 2021, featuring more than 10 international workshops and a series of publications and documents on modern architecture in Southeast Asian countries, including Vietnam.

(3) Docomomo International (Documentation and Conservation of buildings and sites of the Modern Movement) is a non-profit international professional organization dedicated to the research, documentation, and conservation of buildings, sites, and urban areas related to the modern movement, with 71 member countries (https://www.docomomo.com). In 2019, Docomomo Vietnam was officially recognized and became the 70th member of Docomomo International.

(4) Getty Foundation

(5) Architect Lê Văn Lân is one of the leading architects of modern Vietnamese architecture, with numerous achievements and practical contributions. His designed and planned projects include: the Hanoi Children’s Cultural Center, the Thống Nhất Park Gate, Đồng Xuân Market, Hôm-Đức Viên Market, Somerset Hotel by West Lake, Phương Đông Hotel, Hanoi Hotel, Thủ Lệ Park, and the Văn Chương, Quỳnh Lôi, and Nghĩa Đô collective housing areas.

Architect Lê Văn Lân can be seen as a representative of the second generation of Vietnamese architects educated in Vietnam’s architectural training environment, distinguishing them from the first generation of Vietnamese architects trained at the Indochina Fine Arts School under the French curriculum. These first generations of Vietnamese architects made significant contributions to Vietnamese architecture with distinct styles, influenced by their educational environment and professional development.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Architect Phạm Thúy Loan, representative of Docomomo Vietnam

(Photo: Architect Trương Ngọc Lân)

© Architecture Magazine